by Sarvat Hasin

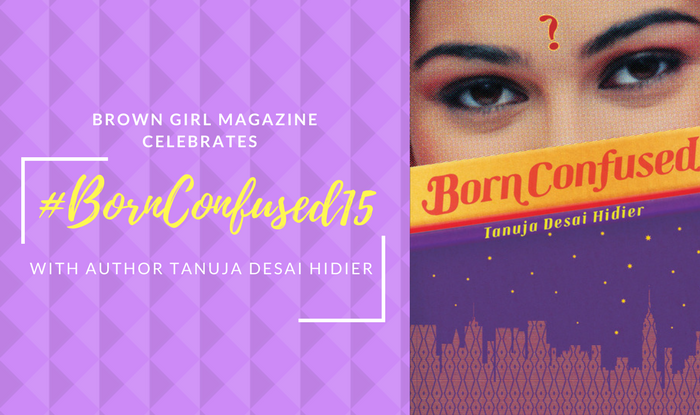

The following post is part of an ongoing series by writers/authors in celebration of the 15th anniversary of the publication of Tanuja Desai Hidier’s landmark novel Born Confused, which is considered to the first ever South Asian American young adult novel (and in part inspired the creation of Brown Girl Magazine!)… as well as the 15th real-time birthday of Born Confused and award-winning sequel Bombay Blues heroine Dimple Lala. #BornConfused15

I read Born Confused the summer I was thirteen or fourteen. I was in London. I lived on library books those summers. I hung out with my parents and sometimes their friends and sometimes their friends’ children but mostly, I read. I found Born Confused during a casual browse of the teenage section, which I strongly believed I was growing too old for. One of those Julys, the library in Ealing was closed for refurbishment so they’d set up a temporary one behind the town hall, a single room with too many sharp corners, busy and dusty. The books weren’t curated as carefully. I read Lolita that year too, thinking the young girl with the red sunglasses on the cover would mean it was written for young girls who wore red sunglasses.

And then, somewhere in the stacks, I found Dimple Lala.

[Read Related: #BornConfused15: Tanuja Desai Hidier’s ‘Dimple Lala’ Opened Doors for Young South Asian Characters]

I had only a vague idea what the book would be about. I think maybe I knew what an ABCD was supposed to be but at the time, I felt distant from the term. I was a Pakistani who lived in Pakistan. What could Dimple possibly have to say to me? I sandwiched it between Nabokov and The Big Sleep, neither of which I would truly appreciate till much later in life. At home, I was determined not to get sucked in too quickly. I resented the idea that the protagonist of this book and I would have anything in common just because we were both brown. Back then, I disappeared into every book I read. Every young female narrator who had ever felt stranger than her friends or too bookish was my reflection. I was Matilda and that girl from Daddy Long-Legs and Lyra from The Golden Compass.

Twenty pages into Born Confused is the scene where Dimple goes shopping for a new outfit for her birthday. I can’t draw outlines to explain its significance: you either get it or you don’t. If you do, you’ve probably been here—sweating in a dressing room with your mother at the other end of the curtain, you trying to squeeze your body into a too-small pair of jeans in the hopes that this will transform you into a different woman: thinner, flatter, whiter. You dream you will emerge from the cocoon with the effortless cool of the girl you most love/hate at school. In the case of Dimple, that’s her best friend Gwyn. And the most cutting sentence in a scene that involves a salesgirl mistaking Dimple’s bra for a top and informing her the sizes she needs are much bigger, and in which Dimple herself compares her body to “a home for the whole country” on account of its apparently “harpoonable” vastness, actually comes from Dimple’s mother. In an attempt to comfort her distressed teenager, she says: “Stop trying to be something you are not.”

There have been enough essays written on teenage girls and their bodies that I don’t need to fill you in on the script: in short, either it’s models on magazine covers or Scarlett O’Hara being strung into her sixteen-inch waist. But at some point in their adolescence, most young women come across the idea that to be thin is to be desirable. In fact, it smacks most of us across the face around the same time we stop being able to eat a cheeseburger without getting any plumper. So: we are given two gifts at the same time. “Thin is good,” wrapped in a layer of “thin is getting less possible.”

With Dimple, with me, there was a third wrapper to this gift: whiteness. The glory of which was unachievable through dieting or exercise.

I wasn’t any more safe from it than she was, even in Karachi. Fair and Lovely [skin-whitening ]adverts glowed down at me from billboards. Paleness was the universal problem of the desi girl, so they sold whiteness to us in tubs. I might have had the great gift of growing up with other Pakistani girls, but this wasn’t sufficient protection. It seeped in like a poison without my really noticing it. Years before I read about Dimple, in games I played with my friends and cousins, I fixed myself under the cloak of imagination. Imaginary me was a mermaid or a witch but she also had green eyes, fair skin, lighter hair. My secret selves didn’t just want to slay dragons: they also wanted to be flawlessly white. There was no specific point in my life when I began wanting this. All I know is that by the time Dimple Lala came into my life—battling with her cultural identity, fretting that the boy she liked preferred her blonde, skinny friend–I already had my idea of a perfect woman and she looked far more like Dimple’s best friend Gwyn than she did like Dimple. Even if I achieved the sixteen-inch waist (spoiler alert: I never did!), I couldn’t switch out the facts about myself. The body I belonged in didn’t just need slimming and squeezing: No pair of jeans would stretch me taller or blanch me whiter. I was stuck in a body that would always be less than.

[Read Related: #BornConfused15: ‘Dimple Lala’s Search for Herself Mirrored my Experience as the Only Indian-American in my Small Town’]

All I know is that by the time Dimple Lala came into my life—battling with her cultural identity, fretting that the boy she liked preferred her blonde, skinny friend—I already had my idea of a perfect woman and she looked far more like Dimple’s best friend Gwyn than she did like Dimple. Even if I achieved the sixteen-inch waist (spoiler alert: I never did!), I couldn’t switch out the facts about myself. The body I belonged in didn’t just need slimming and squeezing: No pair of jeans would stretch me taller or blanch me whiter. I was stuck in a body that would always be less than.

Maybe it’s not surprising that I felt this way: we were fed a culture of slender pale figures. We worshipped Britney Spears, knowing the lines to every single song on Oops I Did It Again as well as we knew the Pakistani national anthem. We lapped up images of her low-slung jeans, her perfectly toned glossy body. Even the Bollywood heroines weren’t quite aligned with us, being mostly light-skinned and Caucasian looking.

And in the books I read, my summer companions, I wasn’t quite safe either. The girls were willowy, descriptions of their thinness, their milky skins, their rosebud lips abounded. Even when the main character struggled with her looks and was meant to be admired for her mind, she still fit into those parameters — just perhaps with a gentle tweak: crooked teeth or acne she could grow out of.

I’ll be honest. I thought we would, too. If you’d told me that ten years from then, that itchy feeling I had would not go away but continue to grow somewhere secret, a place where I could forget it existed until it was everything again, I don’t think I’d have believed you. Back then, I believed we would put away the skin lighteners, bleached hair, colored contacts, and desire to be mistaken for something, anything other than desi when we traveled abroad.

There have been moments of respite over the years. We have found more of our mates in literature, in movies. Mindy Kaling exists, conversations about diversity, about representation, began cropping up. But the issues are deeper rooted than that. Even where desi men take center stage, brown girls are an afterthought — a single date in Aziz Ansari’s otherwise fantastic Master of None, where only white girls are relationship material. A string of caricatures in The Big Sick, where Pakistani women in traditional clothing descend upon the lead character’s house in droves, with headshots of themselves in brown paper envelopes as if they have never heard of Facebook. These women aren’t people: they are just performances of the ethnicity he’s trying to escape.

I was hoping for a real look at what it means to date, to fall in love in a world where the standard of beauty is white. And I still think they could have achieved that without going too out of their way to disqualify brown girls as romantic prospects.

[Read Related: #BornConfused15: ‘Dimple Lala gave me the Lifeline I Needed in the Absence of Community’]

In Born Confused, Dimple’s wardrobe—her sequinned choli and lehengas, the bindis, the jewelry (all markers of a feminine identity she feels out of place with) — is plundered by her best friend. On Gwyn, these things don’t look old-fashioned. They are suddenly sexy, the way yoga is sexy when lithe white girls do it, the way doodh pati gets elevated to chai lattes, and so on. Gwyn’s body is more than just the ideal: it is transformative. It takes what is, to Dimple, hopelessly unappealing, and turns it desirable. It does (for the clothes) what Dimple was hoping the skinny jeans and hot pink militia pants would do for her body. Adds a sprinkle of fairy dust.

But Born Confused doesn’t leave us there. There’s a reason it’s still the book we turn to, 15 years after its initial release. Gwyn and Dimple struggle with their bodies, which are always in conversation with each other, their insecurities, their sense of self-worth. There is a boy, yes, who is the object of their desires. But more than that, there is the sprawl of the New York of the diaspora. Where the clash that Dimple feels in her identities is made physical: Bhangra nights and qawalis, where she doesn’t have to choose between kurtas and jeans. We are allowed to peer into how Dimple’s and Gwyn’s bodies translate between spaces, from their nearly all-white high school to the basement bhangra clubs. And Born Confused doesn’t tear down Gwyn’s attractiveness in order to highlight Dimple’s either. Nor does it fix either of the girl’s relationships with their bodies. It just broadens their awareness of it, of the homes they have — emotional and intellectual — that are more than their physical selves.

The stories I consumed as a teenager were aspirational. They existed to take me out of my narrow bedroom, to different cities, new lives and most painfully, a body that I could be happy to live in.

Dimple Lala was the first character who made me want to stay right here, in my own skin.

[su_divider]

Sarvat Hasin was born in London and grew up in Karachi. She studied Politics at Royal Holloway and then Creative Writing at the University of Oxford. She is fiction editor at The Stockholm Review. Her first novel, This Wide Night, was published by Penguin Random House India and recently long-listed for the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature.

Sarvat Hasin was born in London and grew up in Karachi. She studied Politics at Royal Holloway and then Creative Writing at the University of Oxford. She is fiction editor at The Stockholm Review. Her first novel, This Wide Night, was published by Penguin Random House India and recently long-listed for the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature.