by Shefali Chandan – Follow @browngirlmag

The British “comic paper” Punch (subtitled The London Charivari), ran from 1841 to 2002 and used humor and caricature to comment on the follies and pretensions of the nineteenth and twentieth-century British society. It was the Punch magazine that introduced the term “cartoon” as we understand it today. Fashioned after the French satirical magazine The Charivari, it, in turn, inspired a host of “vernacular Punches” in several British colonies including the Oudh Punch, the Hindi Punch and the Parsee Punch in India.

In its ridicule of British society and the British government, the magazine usually steered clear of being brazenly seditious. Barring that, the magazine mocked and challenged British institutions, symbols, monarchs, politicians and other authorities quite mercilessly. The magazine often took aim at the British aristocracy and later at the middle classes. It also ridiculed colonial rule and politics. While covering India and the Raj, the editors of Punch found to their delight, Indian equivalents of both British nobility and the British bourgeoisie.

The impotent Maharajas of India, further emasculated by the failed Indian mutiny of 1857, found, upon the British crown taking over from the East India Company, that they’d become even less influential and ever more reliant on the good graces of their British overlords. Accustomed to opulent lives but without any political power, these maharajas had to ingratiate themselves to the British for their lifestyles and settle for the crumbs dished out to them. They were often summoned and hauled up to London to meet with those in charge.

“I came to London,

P’rhaps I’d better say how I’d begun,

For, no nabob, was half such a nob,

As the Shallabalah Ma’rajah.

I took three spacious mansions and I threw them into one,

With a door for you, and the other two,

For the Shallabalah Ma’rajah.”

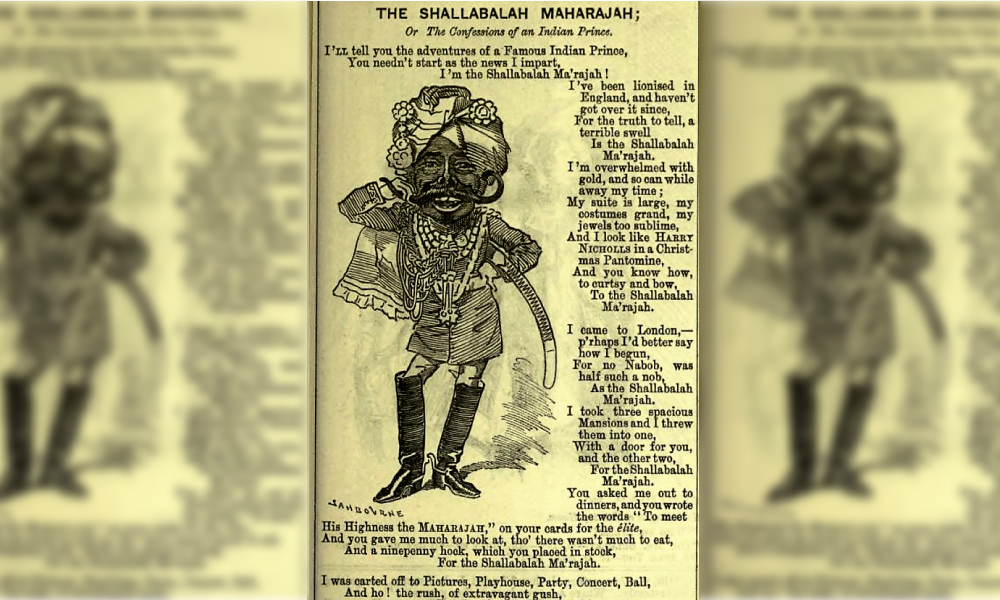

The sort of self-indulgent but lightweight Maharaja, on one such trip to England, is gleefully impersonated in the January 1888 issue of Punch, as the Shallahbalah Maharajah. This bejeweled caricature captures both the frivolity and the piteousness of the diminished Indian Maharaja of the time. But the Maharajah is not all fluff. He’s perceptive enough to realize that his fate and fortunes are in decline. He notices after all how he’s often snubbed, kept waiting at the castle, sneered at, shown only “some tapestries” and given “much to look at, ‘tho not much to eat.” Yet he is loathed to abandon his extravagant ways and so swallowing his pride, is determined to take whatever he can get, even if only “a ninepenny hock placed in stock.”

Fully aware that he might only be a novelty to Britain’s upper classes, he goes along and plays his part, meeting with British elites always looking for some fun and a chance to hobnob with a real “ma’rajah”. For this road show, the Shallabalah Maharajah receives from colonial India’s real arbiters, the only gifts that our sad, fading maharajahs ever would – “a precious badge and star”. And for being a good sport while at it, the added bonus of one whole “bad cigar!”

“I’m overwhelmed with gold,

and so can while away my time,

My suite is large, my costumes grand,

My jewels too sublime,

And I look like Harry Nicholls in a Christmas Pantomine.”

Indian royalty was not the only group lampooned by Punch. The British administration in India, needy of a whole host of office workers and functionaries, created a class of Indians —the Baboos, who took on these roles and then went on to assume along with their clerkships and office duties, the pomposity of their British bosses toward other Indians. The self-important Baboo who used long-winded sentences and simultaneously fawned over all things British was best caricatured by Thomas Anstey Guthrie as Baboo Hurry Bungsho Jabberjee, B.A in 1897.

[Baboo Jabberjee makes a pilgrimage to the shrine of Shakespeare.]

[Baboo Jabberjee makes a pilgrimage to the shrine of Shakespeare.]

An Indian law student in England, “Hurry Jabberjee” aims to please by speaking highly ornate and fussy “Baboo English” and is obsequious to the point of being cringe-worthy. Yet he is oblivious that his language and manners, rather than being impressive, elicit mostly ridicule. Interestingly, an American traveler to India, author Mark Twain in the very year (1897) that F. Anstey created Baboo Jaberjee had remarked on the “language of fawning and flattery” used by Indians toward Westerners (primarily the British). Referring to employment letters that he received for the position of “bearer” in India, he’d noted in his memoir, Following the Equator: “strange as some of these wailing and supplicating letters are, humble and even groveling as some of them are, there is still a pathos about them as a rule, that checks the rising laugh and reproaches it.”

He might as well have been referring to the groveling Jabberjee who generated many laughs among readers or those who knew similar poseurs. Take, for instance, the reverence that a trip to William Shakespeare’s birthplace in Stratford-upon-Avon elicited in the awestruck baboo—

“I have frequently spoken in the flattering terms of a eulogium concerning my extreme partiality for the writings of Hon’ble William Shakespeare. It has been remarked, with some correctness, that he did not exist for an age, but all the time; and though it is the open question whether he did not derive all his ideas from previous writers, and even whether he wrote so much as a single line of the plays which are attributed to his inspired nib, he is one of the institutions of the country, and it is the correct thing for every orthodox British subject to admire and understand him even when most incomprehensible.”

But while the sights and denizens of Britain might have left other awestruck but less precocious Indians (“I am a Kulin Brahmin”) lost for words, Baboo Hurry Bungsho Jabberjee B.A. delights readers with regular streams of gobbledygook as he holds forth on everything he encounters. Here he describes an inter-collegiate boat race:

“The notorious Intercollegian Boat race of this anno Domini will be obsolete and ex-post facto by the time of publication of the present installments of jots and titles, still I am sufficiently presumptive to think that the cogitations and personal experiences of a cultivated, thoughtful native gentleman on this cerulean topic may not be found so stale dry as the remainder of a biscuit. First I will make a clean bosom with the confession that though ardently desirous to witness such a titanic struggle for the cordon bleu of old Father Antic the Thames, I was not the actual spectator of the affair, being previously contracted to escort Miss Mankletow (whose wishfulness is equivalent to legislation) to a theatrical, matutinal performance which…………”

F. Anstey was not the only one to notice the pretensions of the Indian Baboo. Other Brits had remarked on this too including F.M. Coleman, owner and editor of the Times of India who described the Baboo (in this case also the Bengali Baboo) thus: “wanting both in physical strength and moral courage (…) it is to the Bengali Baboo that we are indebted for furnishing a name for the many curious examples of English composition with which most of us are familiar.” Thomas Williamson, an East India Company official had remarked: “(the clerks) affect great erudition, which they are desirous of displaying on all occasions”. But it was the Punch magazine that immortalized the ultimate brown sahib, a peculiar product of colonial rule, as Baboo Jabberjee!

Shefali Chandan is an educator and editor of Jano, the online history magazine for Asian Indian families. She has worked for 2 decades in children’s media at organizations like Scholastic, Time Inc. and PBS Kids. Shefali has always been a history buff and now brings her extensive experience in education to craft high-quality content taken from stories in history for South Asians in America and elsewhere. She lives in Reston, Virginia with her husband and daughter. You can reach her at editor.jano@gmail.com.

Shefali Chandan is an educator and editor of Jano, the online history magazine for Asian Indian families. She has worked for 2 decades in children’s media at organizations like Scholastic, Time Inc. and PBS Kids. Shefali has always been a history buff and now brings her extensive experience in education to craft high-quality content taken from stories in history for South Asians in America and elsewhere. She lives in Reston, Virginia with her husband and daughter. You can reach her at editor.jano@gmail.com.