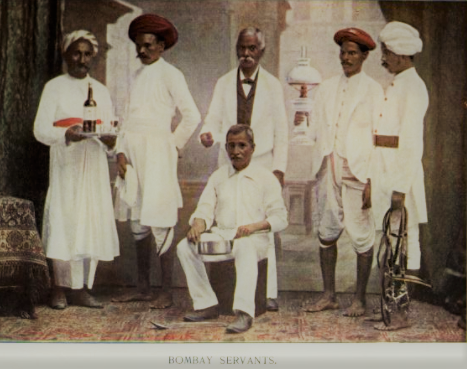

“The ‘Gorgeous East’, if robbed of the vivid coloring which is its greatest charm, would cease to please only one of the senses to which it ever appeals. By the same token, plain photographs fail to convey an adequate idea of the real picture to those whom fortune – or misfortune – has never sent eastward, and it is with a view, therefore, to enable travelers to present to their friends at home a true rendering of the varied and picturesque costumes worn by natives of India in general and of Bombay in particular, that this little book is presented to the public.”

So wrote F.M.Coleman, Managing Partner of the Times of India in Bombay with characteristic condescension, in the preface to a booklet that he produced in 1897, titled, “Typical Pictures of Indian Natives’. Being Reproductions From Specially Prepared Hand-Coloured Photographs with Descriptive Letterpress.” Coleman, an expert in newspaper production, was invited to India in 1892 by Thomas Bennett, the first professional editor of the Times of India and later offered a partnership in Bennett & Coleman, the Times’ holding company. He was only one of hundreds of British residents in India who undertook a systematic study of “Indian natives” during the 200 years of colonial rule. Many a young Briton came to India to make their fortunes, first as employees of the East India company (pre-1857) and later with the British colonial administration. Nineteenth century British families were large—most Britons had 6-8 kids—and as Charles D’Oyly, an artist who himself spent many years of his life in India, put it, working class British men “deficient in their rents”, turned “a longing eye” on India and other colonies, to salvage their “pride and poverty.”

[Read More: ‘The Strongest Bond of Fraternity’: Social, Political And Artistic Links Between India And African Americans Before And After India’s Independence]

British expats who, until the advent of the camera to India in 1840, wanted to share images of their lives with families back home, relied on artists to paint their new environs. In fact, a hybrid style of painting emerged from 1750 onward, fusing (at the behest of Europeans) the stylized and static images of Indian miniature paintings with the more realistic style of European ones. Since most of the patrons of these paintings were East India Company officials, the genre came to be known as “company paintings.” It was this large market for paintings in India that led so many Western artists like George Chinnery, Thomas Hickey, Charles D’Oyly and William Daniell to travel there. They were assisted by Indian artists but as George Forster, a civil servant of the East India Company complained,

“The Hindoos (artists) of this day have a slender knowledge of rules and proportion, and none of the perspective. They are just imitators.”

With the advent of photography in the 1850s, paintings were supplemented by photos, many of which were retouched as was the 1897 collection by Coleman.

The photographs, watercolors, and oils were often accompanied by descriptive notes giving us insights into what the Brits really thought. The commentary with Coleman’s portraiture in his booklet “Typical Pictures of Indian Natives,” is revealing and occasionally even amusing. Mostly, however, it’s supercilious tone makes us balk. Wrote Coleman,

“The Bengali belongs to a class who are as little distinguished for courage as any race in the world. It is not uncommon indeed for them to expatiate upon their own extreme cowardice as if alluding to a special gift“.

Of Parsees, Coleman declared,

“The advantages derived by the natives of India from the British conquest of the country have in no instance been so marked as among the Parsees. Before that event had been consummated, they were literally the hewers of wood and drawers of water for their rulers. At the present time they have been enabled to become one of the most enlightened and wealthy races in the west of India.” “The Bania,” Coleman added, “may have a large house and many servants, with a rubber-tyred carriage drawn by a pair of high-stepping Arab steeds.“ (…) “But when enjoying the privacy of his own house, he often wears a cloth around his loins and nothing besides. His custom is usually to occupy a small room in the rear of the house, where he squats on the ground and eats his rice, as from time immemorial.”

This curiosity about Indians coupled with large doses of disdain was not at all unusual among British residents in India.

[Read More: The Travel Ban Isn’t New: America’s History of Restrictive Immigrant Legislation – Part I]

Capturing images for friends and relatives in Britain was not the only motivation for the prodigious amount of graphic material produced. Ethnographic profiles of Indian people were undertaken to serve colonial interests too. Indians were painstakingly classified by “castes” and trades, ethnicity, dress (“costume”), religion and region. The ordering and codifying of Indian society enabled the British to better know and control Indian society. (All the better to divide and rule?) Other graphic taxonomies included those of Indian plants and animals, birds, monuments, Indian “servants,” places of worship, religious festivals and landscapes. While stereotypes abound in the oral and visual descriptions—elephants, tigers, snake charmers, “nautch” girls, dhobi ghats and funeral pyres make frequent appearances—we can marvel at the rigor and detail with which the documentation and classifications were done.

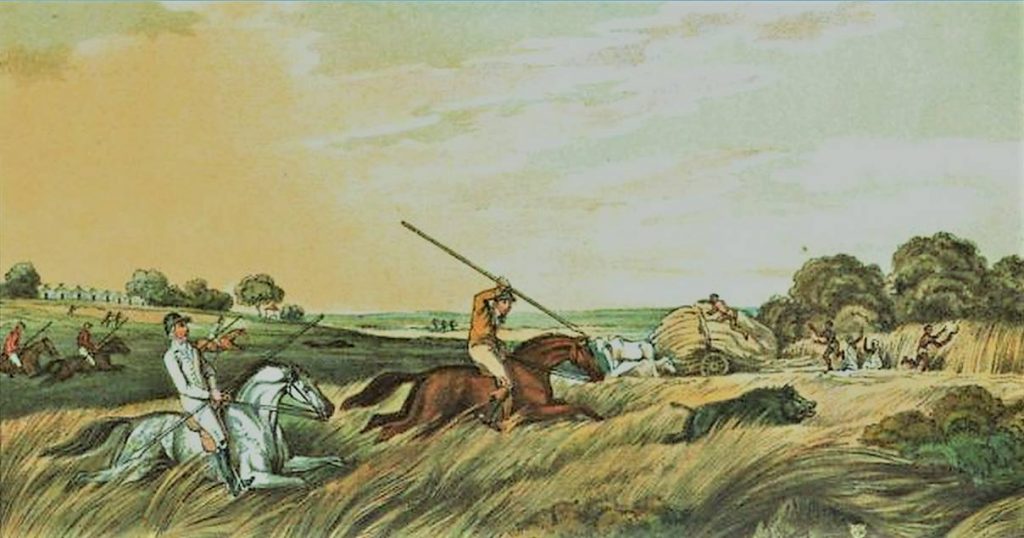

Art was widely used to visually portray British superiority. Britons were depicted as virile, masterful and manly in contrast to “passive,” “effeminate” and servile Indians. To that end, hundreds of paintings captured scenes from big game hunting, a popular colonial pursuit, usually depicting British huntsmen, killing tigers, buffalo, wild boar or other wild game in Indian jungles.

[Hog-hunting in Bengal; from “ORIENTAL FIELD SPORTS” by Capt. Thomas Williamson of the Bengal Army, India, 1807. Phot Illustration by Charles D’Oyly]

[Hog-hunting in Bengal; from “ORIENTAL FIELD SPORTS” by Capt. Thomas Williamson of the Bengal Army, India, 1807. Phot Illustration by Charles D’Oyly]

In the same vein, “Indian servants” were a common theme. As Coleman put it, “The natives of India make excellent servants with even bachelors finding it necessary tto employ at least five persons.” In his book, “The Costumes and Customs of Modern India” (1813), author Thomas Williamson details the range of skills and services that a “gentleman” could avail of. These included sircars (money-servants), shroffs (money-brokers), duftorees (office-keepers), crannies (clerks), bearers, durzees (tailors), khidmatgars (table servants), khansamas (cooks), dandies (boatmen), hiscarrahs (messengers), peons, hookah-bindars (pipe-bearers), hajaums (barbers), ayahs (nurses) and a host of others. Williamson wrote,

“What dilemmas a European is often subjected to among such worthy attendants, each of whom can speak two languages and possess both the will and the means of deception.”

Williamson’s book, illustrated by Charles D’Oyly, offered all kinds of instructions and information on how to cope with Indian servants

“The duftoree (office-keeper) must see that every part of the office be clean, the ink-stands filled, the desks properly arranged, the papers dusted and in general all in readiness for the clerks.”

Of the clerks or “crannies” as they were called, Williamson offered,

“They are with very few exceptions, Hindoos, and obtain situations merely from an ability to write a clear hand with tolerable quickness. It may appear strange, but it is perfectly true that many crannies who can read and write English with fluency and correctness, do not understand one word in ten! Others affect great erudition, which they are desirous of displaying on all occasions”.

The hajaum (barber), Williamson warned,

“Regardless of the wincing and significant looks of the suffering customer, coolly removes not only the beard, but often, a large portion the skin!”

And the sircar (‘money servant’)

“May with propriety compete with the most knowing among our Jews.”

Williamson was cognizant of the criticisms made against some British expats on account of their large retinue of servants in India, but these ‘gentlemen’ were deserving he believed because of the ‘sufferings, privations and danger’ they experienced in India. All told, he concluded,

“With regard to education, morality and liberal principles, the gentlemen of the Honourable East India Company’s Civil and Military Establishments are second to none.”

Shefali Chandan is an educator and editor of Jano, the online history magazine for Asian Indian families. She has worked for 2 decades in children’s media at organizations like Scholastic, Time Inc. and PBS Kids. Shefali has always been a history buff and now brings her extensive experience in education to craft high-quality content taken from stories in history for South Asians in America and elsewhere. She lives in Reston, Virginia with her husband and daughter. You can reach her at editor.jano@gmail.com.

Shefali Chandan is an educator and editor of Jano, the online history magazine for Asian Indian families. She has worked for 2 decades in children’s media at organizations like Scholastic, Time Inc. and PBS Kids. Shefali has always been a history buff and now brings her extensive experience in education to craft high-quality content taken from stories in history for South Asians in America and elsewhere. She lives in Reston, Virginia with her husband and daughter. You can reach her at editor.jano@gmail.com.