In recent years, women’s safety and security has become a pressing issue around the world. Despite many modern-day advancements, I feel that women of this century still have some sorrow deep inside their hearts. It is a feeling of helplessness, vulnerability and concern for their safety. Growing up in an Indian Army background, I got the chance to travel to several cities around India. I always felt very sad witnessing the hardships faced by many women in my country.

Then, on December 2012, a breaking news flash broke the story of a horrible gang rape in Delhi. It was dubbed the “Nirbhaya case,” and it brought women’s rights in India to the center of the world’s stage. I was deeply saddened to hear the news, and it made me reflect on the daily struggles of my fellow women. Almost two pages of my local paper are filled with stories on crimes against women every day.

Poor woman! She gives birth, she cares for her family’s well-being at home, she earns money to support them, and she tries to be the best in all of her roles. If she becomes a victim of rape or abuse, she keeps quiet out of concern for her family’s name. She knows she is the weaker entity in this society.

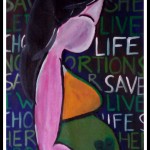

I felt a strong need to do something to support women. I knew I was only one person in this big world, but I felt I should do something within my reach. The idea dawned on me to use my art to give voice to the everyday struggles of the Indian woman. I wanted to use my painting to express her emotions and the issues that she faces from birth throughout the rest of her life. I knew that if I did it right, my art could have a strong influence.

Completing the project took me almost a year. I drew some rough designs on paper. Then, it took me three months to actually make those ideas a reality. My mind was constantly dreaming up color combinations, brush strokes, lighting, texturing, effects and expression. I finally completed the series of 15 works with acrylic paint on hand-crafted textured paper. I never wanted to portray sad subjects with dark colors. In fact, I used bright, bold colors for many of the pieces. Colors do speak, and they can convey a powerful message. The social issues I portrayed are not just limited to South Asian women. The paintings capture experiences and emotions that women around the world can identify with.

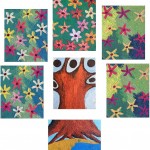

The series concludes with the two paintings titled “Help Us” and “Hope.” The first brings several women together as flowers in a garden. They are burning in a flame, much like their emotions, and are pleading for help. It was important for me to capture these harsh realities, but I concluded the series with a sense of hope, the positive change I hope to see for women going forward. “Hope” is a seven-piece painting that joins together in the shape of a tree. This work portrays the idea that people around the world are uniting to improve conditions for women, forming a beautiful blossoming tree.

My husband once asked me if I would ever be able to produce such works again. My answer was certainly ‘no!’ As an artist, you must get deep into the emotions of your subject, understand its feelings and its mood. I have realized that it is easy to express feelings of happiness, but I found it extremely challenging to paint something so sad and painful. I thank my family for all their support and encouragement throughout this process. Special thanks to my husband , who is extremely supportive and encouraging about my ideas. He is an art lover and my best critic. I try to improve my works with his feedback.

Dipti Kulkarni is a Software Engineer by profession, but her life has always been surrounded with art. She believes that everything can be perceived as an art. As a software professional, developing great code is definitely science and logic, but at some point writing a better code can be perceived as an art. She strongly believes that “art has a great power of love and expression.” She also enjoys Bollywood and Indian Classical music, gardening, home decoration, cooking, baking and traveling. She completely believes in “out of the box” thinking, coming up with some creative and innovative ideas.

Dipti Kulkarni is a Software Engineer by profession, but her life has always been surrounded with art. She believes that everything can be perceived as an art. As a software professional, developing great code is definitely science and logic, but at some point writing a better code can be perceived as an art. She strongly believes that “art has a great power of love and expression.” She also enjoys Bollywood and Indian Classical music, gardening, home decoration, cooking, baking and traveling. She completely believes in “out of the box” thinking, coming up with some creative and innovative ideas.