by Ainee Fatima

Your yearbook quote can leave a lasting impression as you finish up your final year in high school. It’s a lasting legacy that you leave behind, in print. It’s hard to come up with something that sums up your four years perfectly or even the message you want to end your high school career with. That too, in the limited space that is provided under your formal senior picture.

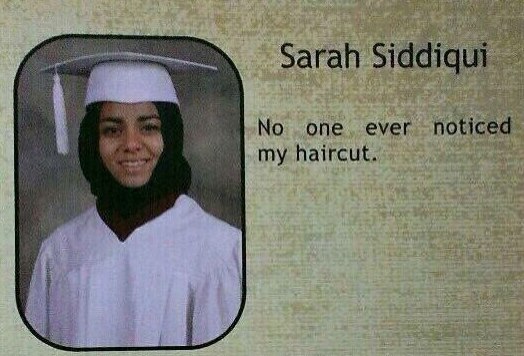

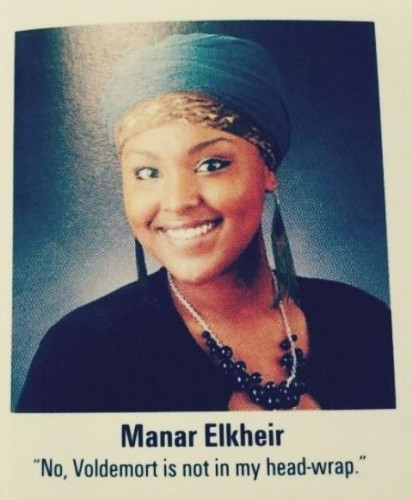

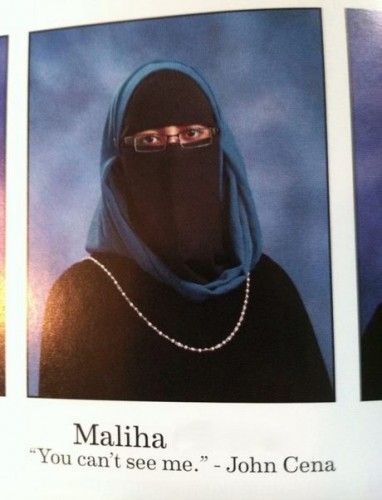

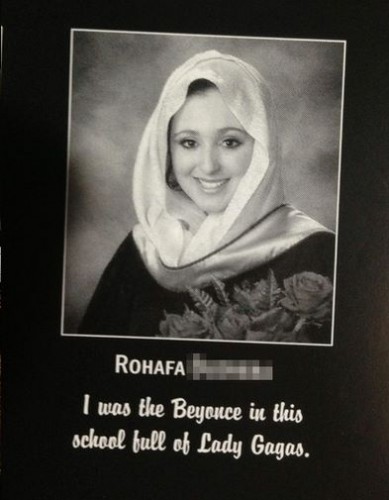

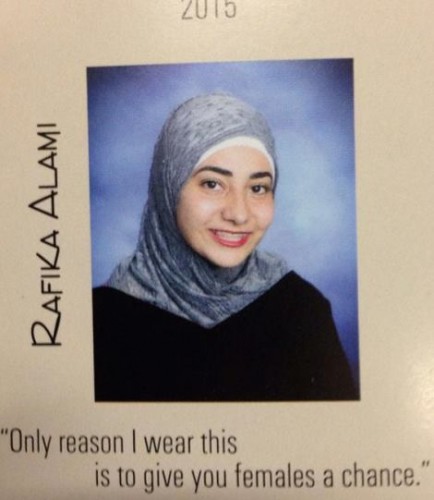

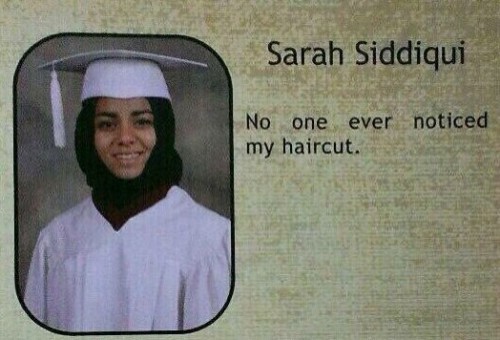

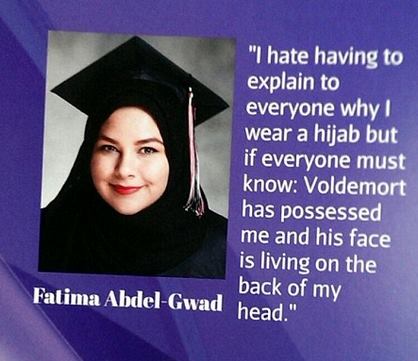

So, it’s entirely refreshing to see Muslim women, generally stereotyped by the media as being subservient and oppressed, use their words so poignantly in the face of widespread, FOX news-induced Islamophobia, of which Muslim women tend to take the brunt of the blow. Also, looks like young Muslim women are just funnier than men. (Where are you, brothers?)

These pictures have been going viral all over Facebook, Tumblr and Twitter. I figured it was time to put them all in the same place, with other like-minded women, in all their glory. Some of these women poke fun at the anti-Muslim gaze, a couple of them find confidence in their choices to wear a headscarf and others speak of the woes of dealing with the number of questions they had to answer about their religious choices.

Overall, these women are able to make you laugh with them in their struggles of being a young Muslim-American who practices Hijab. Meet some of the fabulous young Muslim women below, who find humor in how they’re viewed by their peers when it comes to their religion.

Ainee Fatima is a nationally recognized spoken word artist with a B.A. in Islamic World Studies from DePaul University. Her work deals with Islamic feminism, interfaith dialogue, and diplomacy. You can follow her on Instagram @ainee.f or on Facebook.

Ainee Fatima is a nationally recognized spoken word artist with a B.A. in Islamic World Studies from DePaul University. Her work deals with Islamic feminism, interfaith dialogue, and diplomacy. You can follow her on Instagram @ainee.f or on Facebook.