As Women’s History Month comes to an end, we bring you 15 women of color who we should all take pride in and learn from. Each author listed below—South Asian or not—fought with society’s standards, stigma and sexism to carve her voice on paper, and that takes guts. We applaud them for being our safe haven, and for giving us great works of literature that resonate with the time, speak to the future and others that simply bring us outside of our imaginations.

Jhumpa Lahiri

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

She is a classic voice in the literary canon for women. Lahiri is an Indian-American author best known for her works “The Interpreter of Maladies” and “The Namesake.” The former is a collection of short stories that won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 2000 while the latter was adapted into a popular motion picture starring Kal Penn. She graduated from Barnard College and Boston University and now teaches Creative Writing at Princeton University. She was appointed as a member of the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities by President Barack Obama in 2010. Her memoir, “In Other Words” released in February 2016.

Isabel Allende

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

Speaking of classic literary voices, Allende, a Chilean-American author, is another must-read author in the literary tradition of women of color. Her style has been said to be parallel to that of Gabriel García Márquez in terms of magical realism, and she is most famous for her novels “The House of Spirits” and “City of the Beasts,” which were both commercial successes. In 2014, President Barack Obama awarded her with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Allende’s work, notably, focus on both her personal experiences and on the female experience at large.

Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

Divakaruni is an Indian-American author of fiction and poetry. Her collection of short stories “Arranged Marriage” won the American Book Award in 1995 and two of her novels, “The Mistress of Spices” and “Sister of My Heart” were adapted into films. Her writing focuses on female existential themes and is generally set in India and the United States. She graduated with various degrees in English studies from the University of Calcutta, Wright State University, and the University of California, Berkeley. She now teaches Creative Writing at the University of Houston.

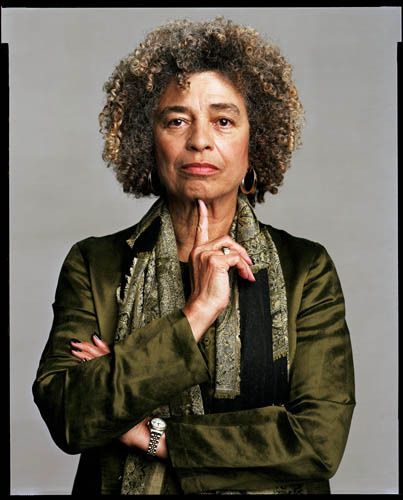

Angela Davis

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

Angela. Yvonne. Davis. Her words will leave you looking at the world in a completely different way once you lift your eyes from the book in front of you. An American political activist, academic scholar, and author, Davis’ work is essential for anyone seeking to engage with complex, and important, theories of social consciousness and social justice. Her latest work “Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of Movement” was released in February 2016.

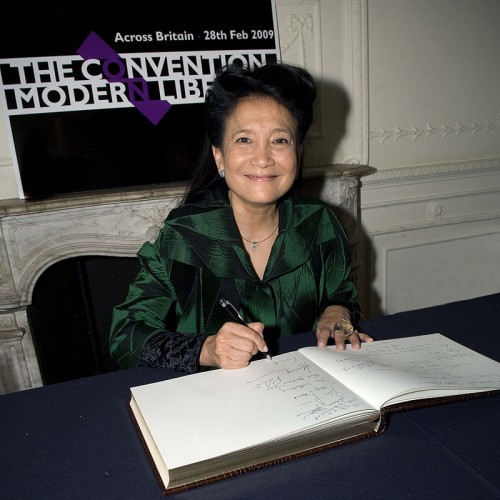

Jung Chang

[Photo Source: Wikipedia]

[Photo Source: Wikipedia]

Chang is Chinese-British author residing in London. Her bestselling autobiography “Wild Swans” was a commercial success, selling over ten million copies worldwide, but is banned in China. It focuses on the lives of three generations of Chinese women while telling a larger story about culture and resistance. She graduated with a degree in linguistics at the University of York in 1982 and became the first Chinese person to ever receive a degree from a British university.

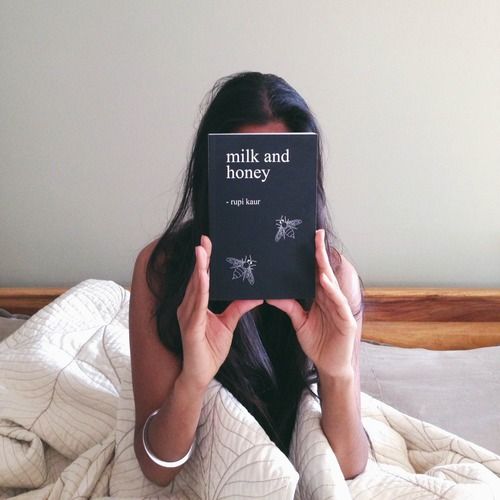

Rupi Kaur

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

Indian-Canadian poet Rupi Kaur is a literary force to be reckoned with. She began her writing career by posting poetry on platforms like Instagram and Tumblr and later published her collective works in October 2015 in the book “Milk and Honey.” Common themes found in her works include femininity, abuse, love, and healing. Her photo essay on menstrual taboos also received wide recognition after it went viral in March 2015.

Nayyirah Waheed

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

The woman who speaks in flowers. Waheed, much like Kaur, first introduced her poetry to the world via social media platforms like Instagram and Tumblr. Her poetry focuses on themes of femininity, love, relationships, race, and oppression. Her collections, “Nejma” and “Salt,” are both self-published successes.

Sandra Cisneros

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

Cisneros is an American writer of Mexican descent whose work deals with themes of cultural hybridity and economic inequality. She is most famous for her books “The House on Mango Street” and “Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories,” with the former currently taught in American schools as a coming-of-age novel. In addition to writing, Cisneros has also worked as a teacher, counselor, and college recruiter.

Monica Ali

[Photo Source: Wikipedia]

[Photo Source: Wikipedia]

Ali is a Bangladeshi-British author whose novel, “Brick Lane,” has been shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. It was later adapted into a film in 2007. She graduated from the University of Oxford where she studied Philosophy, Politics, and Economics. Her writing focuses on the experiences of womanhood and diaspora, particularly as related to the Bangladeshi immigration experience.

Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

Adichie is a Nigerian author of both nonfiction essays and fictional short stories. Her works focus on themes of womanhood, diaspora, race, oppression, and decolonization. Her most famous titles include “Purple Hibiscus,” “Half of a Yellow Sun”, “Americanah,” and “The Thing Around Your Neck.” A self-proclaimed feminist, Adichie gave an inspiring TED talk titled “We Should All Be Feminists,” which published as a modified short essay.

Seeta Begui

[Photo Source: ConstantContact.com]

[Photo Source: ConstantContact.com]

Begui is an Indo-Caribbean author whose work focuses on the feminine experience, resilience, and healing. Her memoir, “Eighteen Brothers and Sisters,” details the powerful story of her struggles and successes—from childhood to womanhood. She also hosts her own radio show, Seeta and Friends, on which she discusses everything from politics to community building efforts.

Hanan al-Shaykh

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

Lebanese author Hanan al-Shaykh is a powerful voice in the canon of contemporary Arab women writers. Her works highlight and challenge the roles of women in traditional, patriarchal social constructions. She has engaged with issues like abortion, sexual promiscuity, and mental health throughout her works, the most popular of which include “Beirut Blues,” “The Story of Zahra”, and “The Locust and the Bird”. She has lived in Lebanon, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and England, and attended the American College for Girls in Cairo, Egypt.

Monique Truong

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

Truong is a Vietnamese-American author who writes about sexuality, diaspora, and race. She is most famous for her bestselling novel “The Book of Salt.” Born in Saigon, Vietnam in 1968, Truong moved to the United States in 1975. She attended Yale University, where she studied English Literature and graduated in 1990.

Julia Alvarez

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

“In the Time of the Butterflies”—Just run to the bookstore and give them all of your money! Alvarez is a Dominican-American author whose work highlights experiences of political resistance, diaspora, and womanhood. She is most famous for her novels “In the Time of the Butterflies”, “How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents,” and “Before We Were Free.” In addition to writing, Alvarez is also the writer-in-residence at Middlebury College.

Michelle Alexander

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

[Photo Source: Pinterest]

Law Professor and civil rights advocate Michelle Alexander recently disrupted the status quo with her bestselling book “The New Jim Crow.” Her writing engages with issues of race and social justice as related to the African-American community in the United States. She graduated from Vanderbilt University and Stanford University Law School, and now teaches at Ohio State University. Her work is poignant, especially during election cycles in the U.S., for all those interested in how various state policies affect communities of color, and in how to dismantle complex systems of oppression.

Elizabeth Jaikaran is a freelance writer based in New York. She graduated from The City College of New York with her B.A. in 2012, and from New York University School of Law in 2016. She is interested in theories of gender politics and enjoys exploring the intersection of international law and social consciousness. When she’s not writing, she enjoys celebrating all of life’s small joys with her friends and binge watching juicy serial dramas with her husband. Her first book, “Trauma” will be published by Shanti Arts in 2017.

Elizabeth Jaikaran is a freelance writer based in New York. She graduated from The City College of New York with her B.A. in 2012, and from New York University School of Law in 2016. She is interested in theories of gender politics and enjoys exploring the intersection of international law and social consciousness. When she’s not writing, she enjoys celebrating all of life’s small joys with her friends and binge watching juicy serial dramas with her husband. Her first book, “Trauma” will be published by Shanti Arts in 2017.