Haroon K. Ullah is a scholar, U.S. diplomat, and field researcher specializing in South Asia and the Middle East. Ullah currently serves on Secretary Kerry’s Policy Planning Staff at the U.S. State Department where he focuses on public diplomacy and countering violent extremism. He grew up in a farming community in Washington State and was trained at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government where he served as a senior Belfer fellow and completed his MPA. He has a PhD from the University of Michigan. Ullah is author of “Vying for Allah’s Vote” and “Bargain from The Bazaar.”

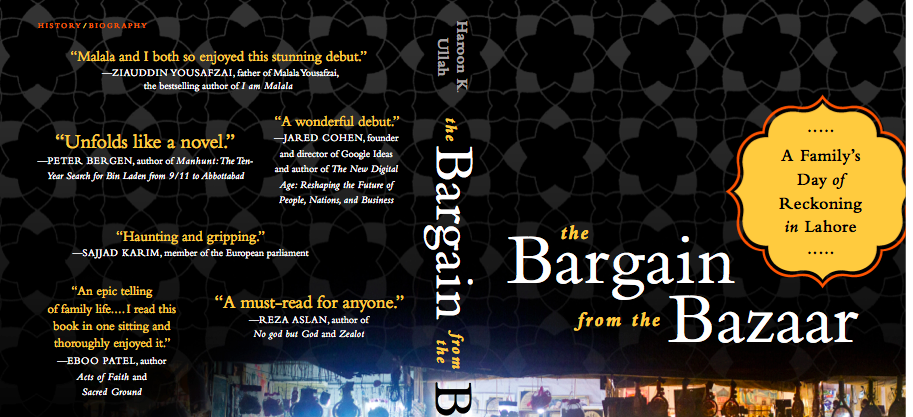

Image provided by Haroon K. Ullah

Having spent many years in and out of Pakistan, both on official business and on my own research trips, I know well the nervous energy that pervades a metropolis like Lahore, where over 12 million people live and work amid the turmoil and terror of the post 9/11 era. Even the slightest boom or bang nails everyone’s attention. It might be just a car backfiring, or it might be a Taliban martyr detonating a suicide vest killing a dozen innocent citizens. On two different visits to the city, I was rocked by the ground-shaking concussion of a car bomb going off blocks away.

This is the background of terror Pakistanis know all too well, the landscape of uncertainty. My research has concentrated on how these terrorist activities, and the general breakdown in law and order, impacts the average Pakistani, the ordinary middle-class family. One thing I learned: when parents are constantly afraid for their children’s safety, the depth of their love shines through in a special way. Show your love now, for tomorrow may be too late.

Among the many wonderful families I came to know, Awais and Shez Reza stood out from the moment I met them in 2004 at a family friend’s dinner-party in suburban Lahore. They had raised three sons and, as I came to learn, gave them all of the support, love and affection one might expect of wise and sensitive parents. One of the dinner guests coaxed Awais into talking about his experiences in a harsh POW camp during the tumultuous 1971 Bangladesh war, and of his harrowing escape across India. He explained that what kept him going through this life or death ordeal was the thought that he must not let his newborn son grow up without a father.

“It gave me a reason to live at a time when I didn’t have many.”

His feelings for family, even when all seemed lost, struck me as especially poignant.

Over the next years, I got to know the Rezas well, and came to understand and appreciate Shez’s quiet strength and endurance. As a nurse in a large urban hospital, she cared for patients who had suffered traumatic injuries, often these were blast victims with little hope of surviving. Shez was trained to remain calm in the face of disaster, and this calm was channeled into the care and upbringing of her three sons. Her smile was irrepressible, her sweetness matched only by her motherly intelligence.

Through the years of their marriage, Awais and Shez Reza have endured first-hand the many upheavals their nation has experienced from the earliest years of its founding. Even with war and terrorism an everyday fact, the Rezas taught their sons the importance of peace and brotherly love, honest work and spiritual reflection. As the excerpt below shows, Awais and Shez were severely tested when one of their sons was caught up in dangerous events that have come to be all too common in Pakistan.

Excerpt from “The Bargain from the Bazaar”:

The knock on the Reza family’s door in Anarkali came late at night. It was not the knock of a neighbor needing assistance or the knock of a family member looking for shelter or the timid knock of the helpless begging for a handout. It was the unignorable knock of authority.

. . .A man in a plain shirt and tie held up an ID card. “Good evening. My name is Jamaz, and I’m a sergeant with the local constabulary, Mr. Reza. I’m sorry to bother you at this hour, but I need a few words with you, if I may.”

“Is Daniyal Reza your son?”

“Yes.”

“Do you know where we can find him?”

“He stays at a hostel in Lahore.”

“Yes, we’ve searched his room. Daniyal has not been there for days. This is a serious matter, Mr. Reza. I realize he is your son, but if you know where he is, you must tell me. It is the law.”

Awais was not intimidated. He’d long ago passed the point where a policeman could frighten him. “I have seen you and another man watching my shop in the bazaar and our house. So you certainly know that Dani hardly ever comes to see us. Why are you looking for my son? What has he done?”

“I’m not at liberty to say, Mr. Reza. Do you know the imam at his madrassa?”

. . . “The truth has been spoken. I cannot tell you where my son is. I simply don’t know.”

“Let me accept that for now as the truth. But I want your word that if you hear from Daniyal or learn his whereabouts, you will let us know. I want your promise.”

Awais shook his head. “I cannot make such a promise. Turn my own son in to the authorities? That I will not do. I will not do your work for you. You might as well take me to jail right now.”

The officer watched Awais’s lined and unyielding face. He finally broke into a half smile and patted Awais on the shoulder. “Very well, old soldier. At least you’re being honest about that. It tells me you are likely being truthful with the rest of it. I won’t keep you any longer, Mr. Reza. Good evening.”

“Good evening, sir.”

When Awais went back inside, he found Shez sitting up in bed, tense and anxious. “It was the police, wasn’t it?”

“Yes. You were right. They’re looking for Dani. For what reason he would not tell.”

Shez fixed her husband with a soulful stare. “Even terrorists have parents,” she mumbled distractedly. “We have to try to find Dani.”

“There’s no way we can do that. We don’t have the contacts that would help us find him. Besides, they’re watching us, remember. We could end up leading the police right to him. And then we’d be implicated too. No, we will not look for Dani.”

Shez said, “I keep asking myself, what did we do wrong? He was a sweet child and always listened to his parents.”