It began with a tweet. “I am bullied and harassed by Trump supporters every day. #MuslimsReportStuff ,” Amelia declared. It was her statement to the world in response to the second U.S. Presidential candidate debate, just days ahead of election day, in which Donald Trump flatly told the Muslim community to report when they see suspicious activity, laying the blame for terrorism at their feet. The next morning, Amelia awoke to her daily dose of bullying magnified by the wrath of social media.

“In just two days, there were over three thousand retweets of my message and over two hundred hate tweets directed at me, my faith, my Prophet and my hijab,” Amelia recounts.

Her experience isn’t unique in the current political landscape, fueled by hate in which the immigrant background has become synonymous with otherness and un-American. The Muslim #MuslimsReportStuff and Asian American #Thisis2016 social media movements are community responses to an all-too-familiar racist tune that has gained traction this year. The rampant fear of brown-skinned Americans has become a regular presence on our social media feeds, in mainstream media, and throughout our lives. That belligerence has fed into an existing thread of racism that existed in this country long before, allowing it to surface, giving it a channel.

Unfortunately, tomorrow is Election Day and the stories of voter suppression are rearing their ugly heads, within this newfound courage. In light of that, the best defense against having your rights infringed upon is a simple act: bring your photo ID with you when you go to the polls tomorrow. Be educated on the laws in your state. If you are a new voter in your state, city, or polling place, be aware of your rights and be aware of local regulations. In Maia’s case below, she was not subjected to the overt vocal racism that Amelia was, but she was put in a situation where her rights were called into question.

[Read Related: Muslims Clap Back at Donald Trump’s Debate Response with #MuslimsReportStuff]

I’ve never had any problems whatsoever. They checked my ID the first time I voted using my new address, probably 5-6 years ago. Since then, [there have been] no ID checks until I voted at the early polling place in my town’s City Hall. The volunteer who gave me my ballot told me he needed to check my ID because the list had me flagged as a “new voter” (which is quite obviously not the case). I’ve voted several times over the last few years, so I’m certainly not inactive — and I checked my registration last night, just in case. He took down my driver’s license ID number and I was on my way, but of the dozens of people that I saw interact with him ahead of me, not one of them was ID’ed. Furthermore, when I snuck a look at the list (after he claimed that my name was flagged), I saw no discernible “flag” (aside from the fact that I’m registered as a Democrat, which was recorded on the list). The whole interaction rubbed me the wrong way. I’ve been voting [in this area] for the last 8 years, and I would’ve never expected this to happen. But it did, and it’s unfortunate. I can only assume that I looked “suspicious”, though as my friends, family, and colleagues have pointed out, I was dressed for work (and I’m a native-born American). It’s a pity, really. But like you note, this is just another reminder that persons of color should carry their IDs with them to the polls this year, even if they haven’t needed them in the past. – Maia

This is not an isolated incident. It is happening across the nation. In an election year where the consequences of voter fraud fear-mongering, fed at least partly by xenophobia, have led to more instances of voter suppression, we have to realize that infringing on our right to vote is not an issue for one race, it is where all brown people must stand together to be counted. We looked into Maia’s state’s laws. To clarify, voter ID laws do vary state by state. In her situation, she was voting in a state where IDs are required if you meet one of the following four criteria:

1) you are a first-time voter in that state OR

2) you are an inactive voter OR

3) the poll worker has some reasonable suspicion of you OR

4) you have to fill a provisional ballot

Maia only fits the third rule, and as such, we have to assume there was reasonable suspicion, but reasonable as subjected to eyes of the poll worker.

One thing that has come up time and time again this year, both for me and for many of the South Asian American community around me, is overt racism. Those sideways looks and that slight detection of doubt you once felt while going about your daily life have transformed into all out declarations of xenophobia, which has been given greater courage and a wider platform this election year. We were always heading in this direction. Trump’s candidacy and candid hate delivery have merely catalyzed what we were unable to face up to.

In spite of being a nation built by immigrants and proud of our humanitarian heritage, we are incredibly conservative and resistant to the next faces of immigration. We are not as welcoming as we like to believe. Each group holds tightly to the advancements, the assimilation, the acceptance, the inroads we’ve made into this patchwork. Historian María Cristina García explains, “part of Americanization is to adopt the values of the society that surrounds you. It becomes a defense mechanism a way of proving your membership in society to adopt those values, to demonstrate that you are a member of the in-group.”

[Read Related: Taking off the Invisibility Cloak: Understanding the Asian American Vote]

I, too, was subjected to an onslaught of threats, anti-Muslim rhetoric, and propaganda upon showing camaraderie with Amelia during the October 9th social media storm of #MuslimsReportStuff. Many of us are accidentally labeled for the color of our skin. I’m not Muslim and I am a proud U.S. citizen, born in New York City to parents who came to what they felt was the best country in the world; to a nation of opportunity where dreams came true. But I didn’t mind being mislabelled. After all, brown people get mislabeled all the time. I’ve been Dominican, Mexican, Brazilian, Pakistani, Colombian, Native American… you name it. How many times do I have to hear someone ask me where I’m from before I say India? Usually three. First I say “New York.” If they persist, I stubbornly declare, “I grew up in New Jersey.” Finally, resiliently, I’ll usually inform them, “oh, you mean my parents? They’re originally from Kolkata but does that matter? I’m Bengali, but do you know what that is? No, not from Bangladesh. I just said my parents are Indian.”

There’s a lesson I hope to teach. That, even for my parents, explaining their heritage is complicated, just as all heritage is. We’re no different in that we are a blend of many races. Technically, my parents are Indian and Burmese and my one grandmother had blue eyes so explain that. Who cares? I say that as an American who believes that while our heritage helps define our identity, we are all Americans. As a person of color, we answer the question, “Where are you from” so much more often than our white counterparts that we begin to doubt whether we belong.

Both of my parents are more American now than Indian, having lived here for the greater part of their lives. They received second sets of doctorates in this country, were stably employed in this country, one of them devoted much of their life for a government agency for this country, are citizens and have adapted to this country. I don’t quite understand the fascination with where am I from. We’re from here. We’ve voted in every election we’ve had the right to.

It breaks my heart to see my parents endure this election, crumbling from the disappointment and shame. My mother, like many in her generation, has seen women face incredible hardship in seeking higher-level roles in society. She, her sister, her mother and her female cousins once fled a fracturing India-Pakistan by dressing as as boys (technically she is from Lahore), her family lost everything they had, they rebuilt their lives, she lived through basically a civil war, yet she now feels more fear than ever before. Fear as a woman. Fear as an Indian American. Fear for her daughter.

South Asian Americans are caught between worlds just as all immigrants were in the past and are now. Like my mother, we are fearful but hyper-aware that life moves forward and all you can do is ride the wave.

Michelle Obama said it best in her famous speech, “We’re telling all our kids that bigotry and bullying are perfectly acceptable in the leader of their country.” And like Donald Trump, many of his supporters who feel a free pass to spew such vile behavior are coming out of the woodwork into the open. One one hand, I believe in the free marketplace of ideas that has come about from this open racism. It gives us a chance to see the shocking truth of our surroundings. This is an opportunity to confront it, just as we would a bully. This is supposed to be the moment when truth enlightens the world, overpowering the lies. On the other hand, right now, that is not the case as people’s rights are being infringed upon. I hear more and more stories like this case of attempted voter suppression today of a fellow South Asian American woman whose name and voting location details are withheld below due to privacy concerns.

We may only represent 1-4% of the voters in America (depending how you break down the Asian race) but voting is our inherent right. On Election Day, know your rights but bring your ID with you. If you experience anything out of the ordinary, if the hair on the back of your neck stands up when someone questions your citizenship, take note and share it. Most importantly, remember, we are Americans, too.

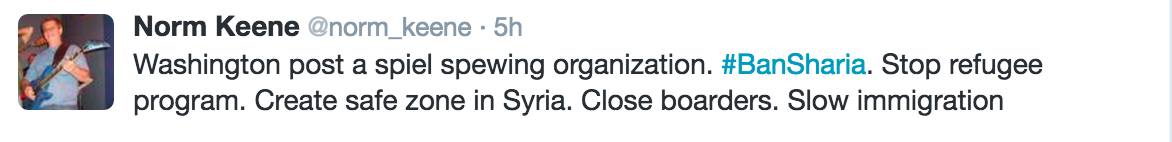

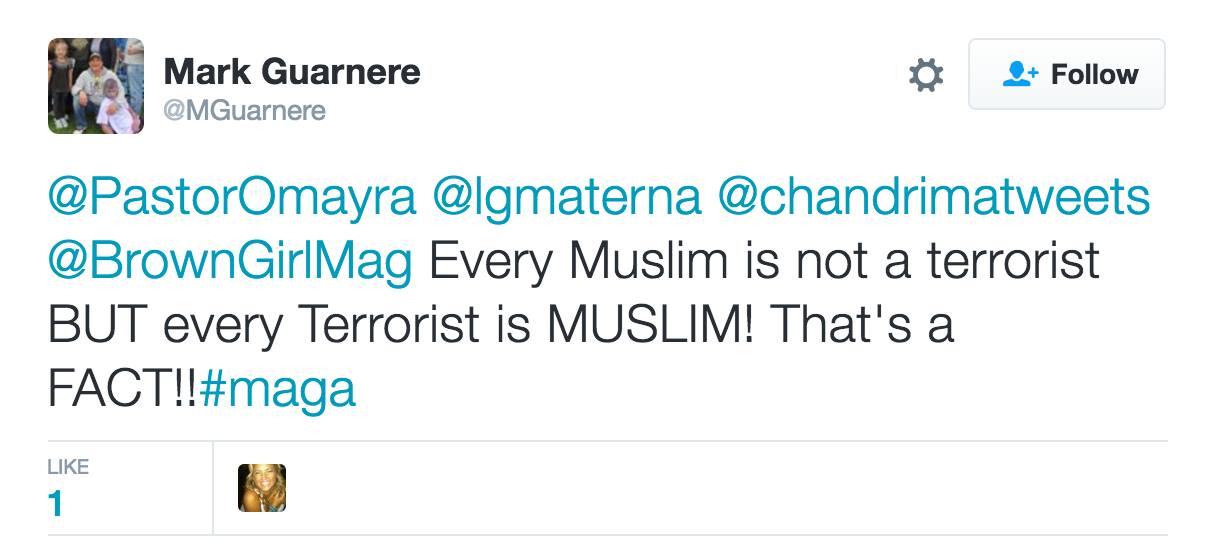

The images below reflect the hate tweets Chandrima woke up to after the Oct. 9 “social media storm.” The graphics are courtesy of Chandrima Chatterjee.

Chandrima is a public health biologist, specializing in cell and molecular biology at the University of Southern California. An avid storyteller in the world of non-profits, soccer and health sciences, she is currently enrolled at UCLA in Media Studies. She’s aiming to increase the awareness, and accessibility, of treatment/prevention of communicable diseases on a global scale. Always looking for the untold story of marginalized communities, and traveling while writing, especially if there’s research and volunteering involved, is what Chandrima loves to do in her spare time.

Chandrima is a public health biologist, specializing in cell and molecular biology at the University of Southern California. An avid storyteller in the world of non-profits, soccer and health sciences, she is currently enrolled at UCLA in Media Studies. She’s aiming to increase the awareness, and accessibility, of treatment/prevention of communicable diseases on a global scale. Always looking for the untold story of marginalized communities, and traveling while writing, especially if there’s research and volunteering involved, is what Chandrima loves to do in her spare time.