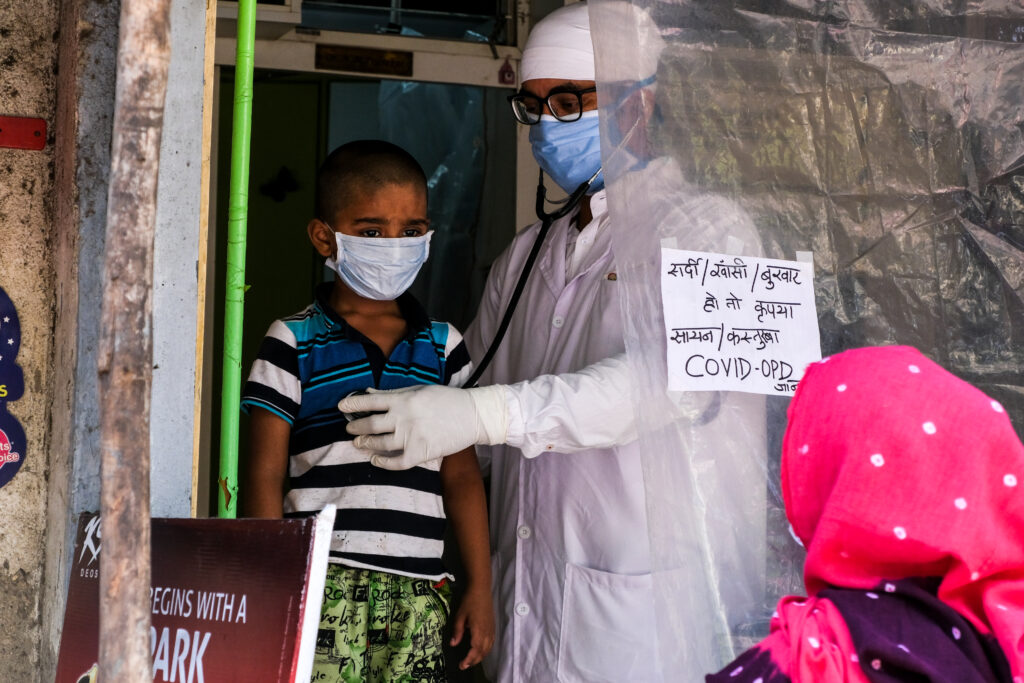

A doctor in India treats patients during the coronavirus outbreak. Photo Source: Shutterstock

Second, to the U.S, India has the highest COVID-19 infection numbers in the world, with more than 10.4 million cases and 150,000 resulting deaths confirmed since the beginning of the pandemic in the country of about 1.4 billion people. To address the novel coronavirus pandemic, India set in motion its plan to vaccinate 300 million people by August on Jan. 16.

Indian regulators approved two vaccines for emergency use on Jan. 3. The first, Covishield, is a version of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine developed in the U.K. Covishield will be manufactured domestically by the Serum Institute of India, the world’s largest manufacturer of vaccines by volume. The second is India’s homegrown vaccine, Covaxin, manufactured by Bharat Biotech. Covaxin was originally intended as a “backup” vaccine, and Bharat Biotech has not yet published Phase 3 trial results regarding its use. On Jan. 5, health officials changed course, saying Covaxin will also be administered in the first phase of vaccinations after receiving patient consent and ensuring follow-ups to monitor effects.

While the Indian plan to export its vaccines to the poorest countries in the world is impressive, some Indians have expressed mixed feelings about the vaccines. Deepak Sehgal, professor and head of the life sciences department at Shiv Nadar University in Uttar Pradesh, explained that while scientists widely believe the vaccines are safe and effective, the existing trial data has not been adequately publicized.

“The problem here is not really safety or efficacy. It is the colossal communication gap. Nobody has been taken into confidence. The Indian population has not been taken into confidence,” Sehgal told Brown Girl Magazine via Zoom.

The U.K. authorized a version of Covishield in December before India authorized it alongside Covaxin. The initial Oxford-AstraZeneca results raised some questions about the trial’s integrity. Oxford-AstraZeneca researchers reported a 70 percent overall efficacy rate, a composite of two separate trials. Some experts have questioned the statistical and clinical validity of reporting this composite number.

[Read Related: A Tale of two Countries: BIPOC are Disproportionately Dying of COVID-19 in the U.S.]

The parameter of efficacy is itself complicated as it can vary based on demographic factors and preexisting conditions.

“Both [vaccine manufacturers] have to have some exclusive markers. They should have studied whether this thing would work in sick persons, older persons, children, or those who are already infected with COVID or are diabetic,” Sehgal said.

Covaxin, developed in India by Bharat Biotech and the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), works differently from the Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca vaccines in that instead of using a synthetic messenger RNA vector, it uses inactivated coronaviruses to trigger an immune response from the body, provoking the creation of antibodies that bind to the “spike” proteins covering the virus’s surface. Representatives from the ICMR state that its differentiated structure will allow it to potentially target mutated strains of the coronavirus, unlike its synthetic counterparts. However, the current lack of Phase 3 trial data has raised concerns from some health watchdog groups and politicians.

Sanjeev Galande, professor of epigenetics at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Pune, explained what he thinks is the source of public controversy over Covaxin in an interview with Brown Girl Magazine.

“There is a lot of emphasis now on ‘Atmanirbar Bharat,’ or the ‘made in India’ initiative. [Bharat Biotech] made the inactivated virus in India, for which Bharat Biotech has huge experience. So many of the vaccines that they have made successfully before come from using inactivated virion particles. So this is basically just following the same technology. It’s just that without the efficacy data, it will be difficult for them to convince the experts,” Galande said during a Zoom call.

Galande also explained that the additional follow-up with recipients required for Covaxin could dissuade people from getting vaccinated in India, where vaccination is not mandatory.

“It’s good to monitor because in the U.S., Moderna vaccine [recipients] have had issues with anaphylactic shocks. Though the numbers are very low — I think one in 90,000 was the frequency of occurrence — it’s important to monitor if the vaccination has any adverse effects on the recipient’s body. That’s part of the phase three protocol, but that [monitoring] might dissuade some people because they think that then they are basically subject to all kinds of things,” Galande said.

In addition to the onerous monitoring process, the implementation of the Covaxin trial itself raised some questions.

“Recently, there was a big uproar after one of the volunteers [in the Bharat Biotech trial] passed away. He was given either a placebo dose or the actual dose, but they can’t unlock the code because these are randomized trials and the code is actually hidden till the end of the trial. These kinds of events basically raised doubt. Once you have these kinds of doubts, it’s like the stock market,” Galande noted.

India’s rollout plan is massive in scale. Already, The Serum Institute of India is sending 2 million doses of Covishield to Brazil and Prime Minister Narendra Modi has expressed India’s intention to export its vaccines throughout the world. Domestically, India, like the U.S. and most other countries, is using a priority list to determine who will be vaccinated in what order, with members of the Army and health workers comprising some of the first in line.

Some believe that prioritization by profession is misguided and that those who have not yet had the virus should receive the first vaccines. Serological tests have implied that nearly a billion Indians have already been infected and thus are likely to already have lasting immunity to reinfection.

[Read Related: 2020: The Pandemic, a Love Lost, and Hope for 2021]

Prioritization is not the only logistical challenge to the Indian plan. Vijayta Fulzele, assistant professor at the School of Management and Entrepreneurship at Shiv Nadar University, explained in an interview with Brown Girl Magazine that both supply and demand are difficult to project in this situation, given the uncertainty in terms of transport capacity and cold-chain storage on the supply side and potential vaccine hesitancy on the demand side.

“If it is understocked, then they are not going to be able to fulfill the demand. If it is overstocked, then the efficacy of the vaccine is quite questionable. Government has to do some accurate estimation of the demand of these vaccines as the demand side uncertainty has a direct impact on dependent demand components, such as syringes, glass vials, and other medical devices,” Fulzele said.

Fulzele is optimistic that India’s detailed rollout plan, if followed accurately, makes the target of 300 million vaccinations by August seem doable. But, she mentioned that supply chain decisions could have been made faster to ensure adherence to the plan.

“I think any supply chain decision has to be made during the development of the drug itself. [In this case], after the drug was developed, the decisions were made based on the demand for the vaccine. Supply chain planning was done after the drug was developed,” Fulzele said.

India is using an app to handle each step of vaccination and dose monitoring. Despite some early glitches in the app, India has a strong track record, as its national vaccination network delivers more than 100 million shots to babies every year. If successful, its rollout will be instrumental in ensuring other developing countries receive the vaccines they need and will provide a replicable model for the world to follow.