Trigger Warning: this article contains mentions of rape and sexual abuse towards children, as well as kidnapping and murder.

If you look up the city of Kasur in Pakistan, the results for the first several pages of your search revolve around a singular deeply alarming phenomenon. The city, just south of Lahore and part of the Pakistani province of Punjab, has in recent years weathered a chain of child sexual abuse scandals, abductions and murders that are as extensive as they are seemingly unchecked. Even with high-publicity cases attracting international attention and the involvement of the country’s Prime Minister, Imran Khan, in administering precautionary measures, the response of law enforcement and government officials to the city’s widespread instances of child rape and murder seem entirely disproportionate to the severity of the crisis.

As recently as this past September, protests broke out in Kasur after the discovery of the bodies of three boys, all under the age of 10, who had gone missing between the months of June and September. One body was found in full and the other two in a decomposed state. The post-mortem examination conducted on the body of Faizan, 8, revealed that he was raped prior to his murder. The discovery of the children’s’ bodies sparked outrage, with the local trade and bar associations calling for a strike, and protesters pelting a police station with stones as their anger towards the perceived inaction of law enforcement authorities came to ahead. Two weeks and 1,700 DNA samples later, the police arrested Sohail Shazad, a local rickshaw driver who confessed to luring the children with money and free rickshaw rides, then raping and strangling them to death.

[Read Related: Priyanka Reddy: 7 Years After Nirbhaya Women Still Unsafe in India]

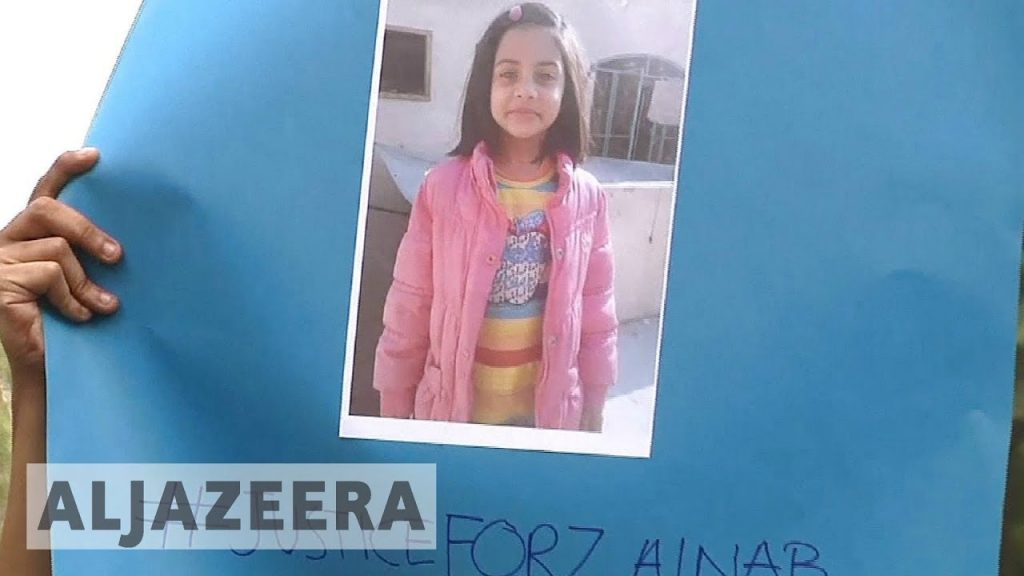

Kasur first received global attention in 2015, when the uncovering of an extensive pedophile and pornography ring that abused more than 280 children since 2006 made it home to the largest child abuse scandal in Pakistan’s history. In January of 2018, the city again made headlines following the disappearance of 6-year-old Zainab Ansari, whose body was found five days later in a rubbish dump, having been raped and murdered. In both cases, regressive social attitudes and negligence on the part of law enforcement officials stood in the way of justice.

In the aftermath of the 2015 incident, victims of the child pornography ring fled Kasur, having been conditioned into feeling ashamed, being blacklisted by the rest of the village’s residents, or hopeless in the face of the authorities’ consistent failure to bring perpetrators to justice. In the second case, it was Zainab’s relatives, not the police, who recovered the CCTV footage of her last moments that lead to the arrest of Imran Ali almost 3 weeks later. Following Zainab’s death, protests in response to police incompetence killed 2, and it was mounting public pressure and the widespread circulation of the #JusticeForZainab hashtag that lead to Ali’s execution in October of the same year, an anomaly in Pakistan’s notoriously complicated and slow-moving judicial system. Residents of Kasur being interviewed following the most recent murders also described a double-standard when it comes to the gender of child victims. A girl being abused is a crime, but for a boy, being sexually abused or assaulted is common, almost seen as a rite of passage, and as with most rites of passage, the abuse is cyclical. Shazad, arrested for the rape and murder of three boys in the latest incident, revealed to police that he himself was sexually abused at his workplace for 12 years.

At the moment, authorities in Kasur are focused on preventive measures. Planned initiatives include educating the public about sexual abuse at Friday sermons at the mosque, and organizing events for parents to raise awareness on how to keep their children safer. The latter measure was put into practice in a number of schools around Kasur district following Ansari’s murder. This past October, Pakistani Prime Minister announced the creation of an app that will allow parents to report a child’s disappearance immediately, alerting officials in all four provinces of Pakistan. Khan also announced the removal of a number of senior police officers in Kasur, on charges of negligence.

[Read Related: Patriarchy and Rape Culture Create Blame Game Instead of #JusticeforZainab]

In the last year, over 3,000 cases of sexual abuse towards children have been reported across Pakistan, according to Sahil, a child rights organization, Al Jazeera reported. While laws have been amended and formulated to address these issues, implementation is lacking.

Our laws are certainly strong enough for convictions in child abuse cases,” says Manizeh Bano, Sahil’s executive director. “The problem remains with implementation.

Child-friendly courts have been set up in parts of the country, where children can attend during certain hours to avoid confrontation with adult abusers, however, there is a gap in addressing a child’s psychological needs or mental health, Sahil has found.

When children come to court they should have a screen in front of them so they can testify without having to face their accuser, Bano told Al Jazeera.

To allow for children to testify in safe environments, Kasur is working to conduct home visits for statements instead of forcing children to testify in police stations or courts. Most recently, the Pakistani National Assembly approved the Zainab Alert: Recovery and Response Bill, two years after Ansari’s body was found in Kasur. The bill was presented last year in June but passed into law last month. Under the legislation, the maximum sentence for perpetrators of child sexual abuse has been extended to life with a minimum of 10 years; a hotline has also been set up to report missing children. Due to the limited jurisdiction of the National Assembly, the legislation can only be implemented in certain provinces. Once passed nationally, the bill will allow for reported child cases to generate automatic alerts.

Still, for many parents, these measures are too little, too late. Ongoing police investigations delay the return of the victims’ bodies to their families, and many have been thrust into further poverty, having left work to search for their children and taking out loans to print posters and get whatever information they can. Every new murder is a wrenching reminder of how authorities in Kasur continue to fail its children, first with negligence, then with injustice.