Amidst a rural Connecticut town in the height of autumn splendor, ancient Hindu traditions are quietly celebrated at home. Nearly 3,000 miles south, fireworks envelop Guyana’s warm sky. Clay lamps and colorful decorations line every corner. Family and friends visit temples, attend parades, and parties for days. In both locations, there is a hope of newness in the air. It’s Diwali, the auspicious festival of lights that beckons the triumph of goodness over ignorance and evil. Women representing the goddess Lakshmi (the ultimate embodiment of female power) are revered as a source of light in their homes and, by extension, society. While this seems ideal, we can’t forget the deeply rooted gender inequalities that exist in stark contrast to the holiday.

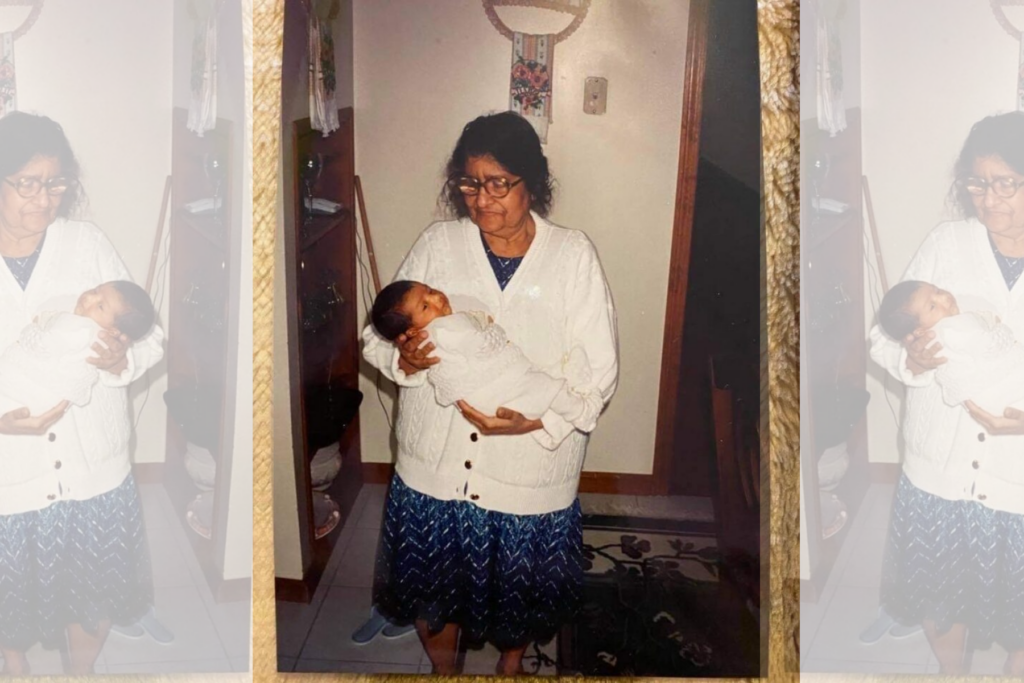

Back in Connecticut, I lay in bed meekly reciting a Lakshmi mantra. Dazedly, my mind wanders to the personal significance of the holiday’s symbolic meaning. Growing up, I was enamored with the celebration of a female deity. My family’s teachings exemplified women as manifestations of strength and perseverance despite the sacrifices and injustices that frequently marred the experience of womanhood. Immediately, I remember my grandmother Indranie — a woman who encompasses this pioneering vigor, facilitating the togetherness that still binds our family after years of adversity and geographical distance. She was a modern portrayal of extraordinary female endurance, teaching us cultural traditions while pushing us past our circumstances. Desperately, I yearned to be like her and the goddess, revolutionaries who knew their self-worth, adored their identity, and actively worked to modernize it.

[Read Related: Queens Girl: Indo-Caribbean Life in ’90s New York — the Fight]

After emigrating from Guyana in the 1980s, my mother’s family settled in a red brick house across the Long Island Sound, next to the well-known Indo-Caribbean community of Queens, NY. Before Hurricane Sandy ravaged the area, my grandparents sat on two parallel living room white sofas that were the center of family activities. I’ll never forget when my father and I sat with them to watch the news. From his sofa, my grandfather slightly reprimanded my grandmother, “What do you even know about economics?” Lying opposite, she responded swiftly.

“Do not ever tell me what I do and do not know.”

Our jaws dropped. Barely 4’11,” I never forgot the authority in her tone and the power behind her steely blue-gray eyes. Years later on that same white sofa, I asked her opinion on gay marriage. At the time, it was illegal in America and I braced myself for an answer I anticipated disliking. She turned to me and smiled, surprising me with her answer. In her soft Guyanese accent, she said,

“They are all God’s pickney, why does it matter?”

These two memories are forever imprinted in my mind. My grandmother showcased that change in traditional mindset is possible regardless of your culture or age. She taught me that even in small instances, a woman has the ability to stand up for herself. It wasn’t some brash display of rebellion, but rather examples of how a woman should use her knowledge and experience to articulate her beliefs. There, I saw her as an unequivocally confident and assertive woman.

Born in the seaside village of Essequibo to a traditional Brahmin pandit brought from India by the British, my grandmother illustrated strong leadership qualities from an early age. She dreamt of going to school instead of marriage. Denied the opportunity to become a teacher due to restrictive gender roles in education and employment, she was married at the age of 13 to my pandit grandfather and luckily fell in love. She led a home of 12 children, many, who went on to become successful leaders.

[Read Related: ‘Broken English’ to Others, but Rich History to Me]

In Essequibo, my grandmother was the first woman to drive a car and cut her hair short. She would admonish husbands publicly beating their wives by picking up a cutlass to threaten them and ushered their battered wives into her home for safety. She broke up forced marriages disregarding societal repercussions from fellow villagers or her own elevated social status. At the peak of racial tensions between Afro and Indo-Caribbeans in Guyana, she had political revolutionaries over for chicken curry and engaged in discussions regarding the creation of a new and more equitable society.

When my grandmother came to America, she advocated for her daughters and granddaughters to wear pants, focus on education, and marry a person who accepted them as they were. For years, she slept on the floor and offered the bed and couches to family members so they would be rested for work and school. At one point, there were 40 members living together, yet she made sure everyone had a portion of the little food that was available. There were moments when she even covered for my female cousins and allowed them to go meet boys unbeknownst to their parents!

And yet, my grandmother fully embraced her heritage, accepting that her morals innately stemmed from our rich Indian history. She was a stout believer in karma and prayed daily. She advocated for marriage, encouraged close-knit family units, and spoke out against her ideas of indecent behavior irrespective of gender.

Pujas, spices, and bhajans often filled our home, and she consistently spoke of the importance of rites and preserving values. My grandmother never once felt the need to adopt a new identity or change to fit in. Similarly, she never wanted her family to feel they needed to change our Indo-Caribbean identity in order to increase their self-worth or assimilate. She knew our story provided us with a rich background that should not be erased.

During the course of her lifetime, my grandmother embraced the balance of tradition and progressivism. She understood the difficulty of being a woman living between two contrasting ideologies. Indo-Caribbean women today are evolving and reforming cultural practices that simultaneously allow growth beyond our traditional roles and preservation of our cultural identity. While her story is different than mine, my grandmother ingrained in me that I should never be ashamed to embrace both tradition and modernity.

Both my grandmother and her white sofa are gone now, her ashes taken by the ocean. I work hard for the life I want in her remembrance. Attached to my Guyanese culture, but not afraid to vehemently speak out against archaic notions, I find a balance. Her wisdom and my childhood memories of our family have fundamentally shaped me into the proud first-generation Guyanese woman I am today. As we are surrounded by pain and uncertainty amidst our country’s recent events, I draw comfort and strength from my grandmother’s instilled values and most importantly from those conversations on the white sofa.