My name is Ankita Mishra. I was born in Ohio and grew up in New Jersey, though that is not what people usually want to hear when they ask where I’m from. I am an emerging artist which means I support myself by bartending — and I get asked “Where are you from?” with increasing aggression every Friday, Saturday and Sunday night. My parents moved to this country in the ’70s to pursue their education (they are not happy with my career choices). They have educated me in many subjects — my own Bihari and Hindu background, physics, world religions, cooking, and the urgent art of not questioning authority and keeping my mouth shut.

Though I pride myself on being outspoken, I stop right before the punchline. There is a moment, right before I give someone what they’re due, when I retract. It’s the same invisible line my parents give up at, the aunties and uncles whose brazen voices dim to a whisper in mere seconds when a cheery, Midwestern voice asks them to spell their name over the phone.

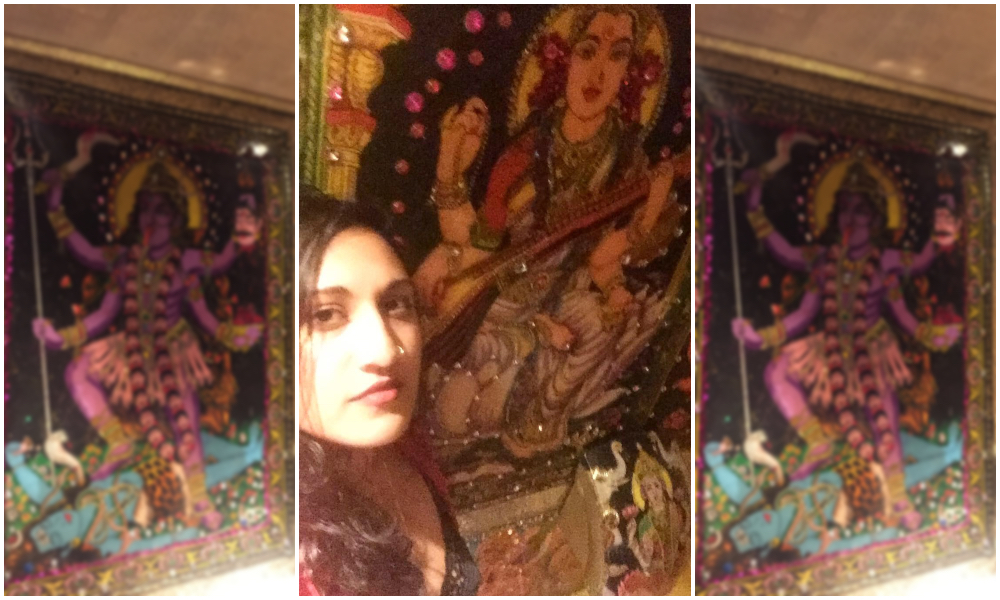

That is why last month, during a night out with friends, I could not stay quiet when I suddenly found myself in a curiously-decorated VIP bathroom inside House of Yes in Bushwick, NY. The walls were papered with bejeweled images of Hindu gods like Ganesha, Saraswati, Kali and Shiva.

You can see what the bathroom looked like here.

This is the price of silence. The scales will always tip back to favor the status quo, the inherent whiteness of the spaces we enjoy. Our Hindu holidays and festivals, our grief and history, will only ever be presented as an accessory to American and European conquests — forever owned and forever used as if there are no consequences.

But there are consequences. I wanted to be heard this time. So, I took a deep breath, picked up my phone, and sent a strongly worded letter to the venue’s general email.

To Whom it May Concern,

Oct. 3, 2018

As a queer woman of color with a hyphenated identity in 2018 America, I am used to silencing my voice in the service of keeping peace in public. However, after posting about my experience at House of Yes this weekend on Facebook and Instagram I feel pushed to approach you directly. I trust that House of Yes is a venue where I might actually be heard, and where change for the better can occur.

I came to the Endless Summer last Saturday, Sept 29. Being a resident of Brooklyn for over a decade, I frequent House of Yes whenever I can after my bartending shifts up the street. I have had too many beautiful moments here to recount: dancing at the Pride after-party with my partner, for instance, taking her to a show as one of our first dates as a couple, coming here with friends to relax and feel free and dance. I used to take Silks classes with Anya Sapozhnikova back in the Maujer Street days and have always been so invested with love and admiration at the growth of House of Yes. I have always been annoyingly proud and vocal about how much affection I have for this club, your mission statement, and your intentions for revolutionary inclusive programming.

I was not proud on Saturday night. I was there with a group that had ordered a bottle service table to the side of the bar and because of the high price they were paying, I had the privilege of accessing the private bathroom behind the DJ booth by the stage. You know the one. At first when I reached for toilet paper from the dispenser, it did not register that I was looking at Mahadev. Slowly I raised my eyes to take in the room and noticed all of them– Ganesha, Saraswati, Brahma, Shiva, Radha and Krishna, Lakshmi, and inexplicably right above the toilet, Kali. I was inside a temple but it was all wrong– I was wearing shoes, I was peeing, and my ass was out.

It is unfortunate that the ripples of colonialism have such long-reaching waves. I am Indian-American. I have been in this position before, countless times. I used to be a Teaching Artist at the Rubin Museum of Art, where I was constantly confronted with microaggressions and a lack of power and ownership over my own culture. Fighting misconceptions and the misuse of my culture is a daily- no, minute by minute battle. But to be faced with such blatant cultural appropriation when I was relaxed, a little drunk, and surrounded by people I felt championed by was too jarring to ignore.

Let’s say, the person reading this is confused. I have spent so much time in my head breaking down how to explain why this is so wrong. Here are some bullet points:

1. Cleanliness and purity are obsessive rules in an Indian household. Around Indian deities it is a very basic form of respect, one that you learn as a child. You cannot present a flower to a god after having smelled it– you cannot wear shoes in a temple. Peeing, shitting, throwing up and all other activities that happen in nightclub bathrooms would also go under the category of uncleanliness.

2. Hinduism does not believe in eternal damnation. It has not also, conquered, traumatized and converted whole civilizations and countries as part of its mission. It does not have the same history as, for example, Christianity. There has never been a “Reformation” period in Hinduism. I cannot speak for every South Asian/ South Asian descendant on the planet, but I have not seen the same level of angst and irreverence towards its icons. There is no “Piss Christ” art piece equivalent, no cultural Satanic movement that battles each of its innumerable goddesses and gods. Therefore the same rules that apply to Christianity simply are not applicable in Hinduism. You cannot impose your own punk and subversive cultural standards onto another religion. It is just another form of misinterpretation and desire to control something that is not yours.

3. Hindu, Buddhist and South Asian culture continues to constantly be exploited through Western capitalism in the name of spiritual awakening and sexual exploration. Our culture is not a ticket to your self-discovery. India was under colonial rule for 200 years and I, frankly, am tired of how uneducated America seems to be about that. Do you think you would even be in that yoga class if it hadn’t been perfectly packaged for you to consume?

4. Maybe someone thought it would inspire “instant enlightenment” one night on the dancefloor. Wrong. Tantric Buddhism is different from Hinduism and at any rate, ya got those deities wrong.

5. I only saw this because it was a private bathroom reserved for those customers paying over $600 for a bottle of Grey Goose. I imagine that clientele is used to dining at Buddakan on a regular basis and does not even fully take in the fact that an entire ancient culture and religion is being reduced to a playscape for their vices and routine board meetings.

6. I have spent 3 days (now 4) thinking of every angle that could have led someone to make this tone deaf mistake. The point is, no one took even a fraction of that time thinking of how it would make someone like me feel. As I sat on the toilet, I thought “Is it possible that my culture is again being dehumanized and treated like an accessory of white culture, here on Jefferson Street?”

I am going to go home to my parents house in November to celebrate Diwali, a holiday commemorating each deity featured in your bathroom. This is an active religion, practiced today. My true desire is to see the bathroom taken down. My parents would not have had the courage to stand up for what is right, but I as their daughter, do. Your mission statement is one that touts inclusivity, positivity and safety. Please don’t make me lose faith in the ability we all have to right some wrongs and truly hear each other out.

If you made it to the end of this letter then I thank you for being open and receptive.

Inclusivity now.

Namaste,

Ankita Mishra

Then, the unimaginable happened. I GOT A RESPONSE.

Hi Ankita,

My name is Kae Burke, I’m Anya’s partner as a co-founder/creative director at House of Yes and I am the one that created, conceived and made the deity bathroom. I am fully responsible for making the tone-deaf and completely ignorant decor choice.

I am sorry for not taking the time to fully understand and research the deep history of the culture I was inspired by before using it to decorate. I feel awful that you had to experience this type of cultural disrespect at House of Yes of all places.

I hear you loud and clear and the tone-deaf appropriative/offensive bathroom will be dismantled and redesigned ASAP. To be transparent, the soonest I can take it on is right after Halloween. If you insist, we can put paint over it until then.

I read every word of your email (twice) and I wanted to thank you for taking the time, being bold yet informative in your writing and also trusting us in that you would be heard.

If you’d like to discuss over the phone I’m reachable at —–.

Thank you again,

Kae

I had broken my silence and spoken up. Kae’s response was everything I had convinced myself was impossible: an apology. And yet why did I fear her apology so much? Is it because some hurting goes so deep, genuine remorse cannot erase it?

I had to chant to myself: I am grateful for the positive outcome of this exchange. I am grateful I was able to communicate with an empathetic and understanding person. But at the end of the day, I do not feel warm and fuzzy about this exchange, even though I do think we made some progress. In my most recent conversations with Kae, she wanted to re-decorate the bathroom walls with images of human rights leaders and notable feminists in place of the deities. The final solution will be to paint these images over the deities instead of dismantling the walls entirely. It left me hungry with wonder.

What is progress? What is the difference between role models, important feminists and religious deities? What are the events that lead to my interaction with House of Yes and can it truly be solved without a fight? Where is the line of what can be put into a bathroom?

“Speak up!” my mother yelled to me constantly as a child, though she blushes modestly when asking a young, blonde waitress where the bathroom is in the Olive Garden attached to the mall. I have seen both of my parents accept their subservience to white American culture my whole life, never asking to take up space or be respected for it. So now as their hybrid daughter I do it for them, and I hope to god(s) there are others like me who will.