by Saadia Faruqi – Follow @BrownGirlMag

This post was originally posted on Muslim Observer and republished with permission.

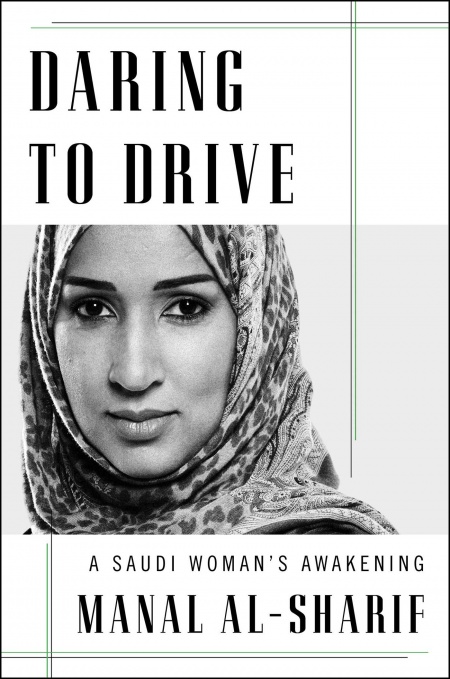

A recent memoir published in the United States has given a fresh look at the living conditions in one of the world’s most repressive nations: Saudi Arabia. Manal al-Sharif, Saudi activist who was jailed for the crime of “driving while female” has written a tell-all book about her life in Saudi Arabia, and she doesn’t shy away from ugly truths such as child abuse, extremism, and governmental injustice.

Manal comes from a poor family, living in the ghettos of Mecca far away from the rich and easy lifestyle of Saudi elites. She describes her living conditions as terrible: small apartments without running water, filthy conditions, and restrictive environment.

“Saudi families, almost universally, reflect a contradictory combination of extreme intimacy and extreme segregation and impenetrable privacy. We sleep in common rooms and travel in and out of each other’s apartments, but we keep our windows covered, and indeed often have windows that face the outside world. In many houses, men and women live on different sides and enter and exit via different doors. We are a culture of peeking, where women peek from behind windows or on the other side of doors to see who might have come to visit.”

Her school is a tool for the regime, teaching subjects like loyalty to the king and checking for signs of modernism, such as a hairband or nail polish, colored shoes or a bracelet. Teachers ruled with strict, authoritarian style no less abusive than her home life.

“When it came to beatings, our schools were no better than our homes. I remember the expression uttered by many parents when they registered their children, which translates literally to: “The skin is for you, and the bone is for us.”

Manal spends many pages describing the oppressive fundamentalist ideology that Muslims in Saudi Arab practice. She talks about the obsession with the niqab, about labeling non-Muslims infidels, about rejecting many things like music and television from their lives. At the age of thirteen, Manal joins the thousands of other Saudi youth as they embrace this extremist ideology promoted by the clerics.

“I know the exact day and event that transformed me at the age of thirteen from a moderately observant Muslim into a radical Islamist. Until that moment, my shift has been a slower, more cumulative process, a series of adaptations and accommodations. But after this particular afternoon, I became almost unrecognizable to my younger self. I became extremely observant, down to the most minor acts; I renounced nearly every small pleasure I had known as a girl; I brutally enforced my new beliefs upon my family. And I can say with certainty that this happened as a direct result of the environment I lived in, from my schooling and education to the radical preachers broadcasting on TV; the cassettes and VHS tapes of their fiery sermons; the books and leaflets that were distributed for free in common gathering places, like the souk, our local market.”

This phase doesn’t last long. When Manal grows older, her extremism fades, and she is frustrated by the lack of freedom women in Saudi Arabia have. She cannot travel without a guardian, she cannot get an identity card or a job or even a decent education because the rules for girls leaving their homes are so strict. Most of all, she cannot drive.

This phase doesn’t last long. When Manal grows older, her extremism fades, and she is frustrated by the lack of freedom women in Saudi Arabia have. She cannot travel without a guardian, she cannot get an identity card or a job or even a decent education because the rules for girls leaving their homes are so strict. Most of all, she cannot drive.

Manal’s activist spirit kicks in, and she joins a driving group on Facebook which encourages Saudi women to drive. Quickly, she becomes the face of the event, interviewed by western journalists in the U.A.E and other nations. But in Saudi Arabia, she was either ignored or scorned.

[Read More: “Kavita Mehra Talks About Sakhi, A Vehicle That Drives Female Empowerment Forward“]

“It was hard not to feel rattled by the comments, particularly those left by men on our Facebook event page. Over and over, they equated the Women2Drive campaign with women who were loose, sexually compromised, and of weak, immoral character. The comments were menacing, saying very directly that our campaign was designed to corrupt young girls and that we were “betraying Islam.”

When Manal finally drives on the streets, she is arrested, harassed by police and threatened with her life. She finally gains release when her father begs forgiveness of the King and has to pledge never to drive again. She receives punishments from her employer, clerics call her evil and traitorous in their sermons, and her family is harassed. All the while women’s lives in Saudi Arabia remain unchanged.

For readers who are unaware of the dirty side of Saudi society, “Daring to Drive” is an eye-opening account of everything the world has missed. Manal herself is hopeful though.

“The rain begins with a single drop,” she often says.

“Daring to Drive” is available on Amazon.