“Throughout the day, I continuously wonder if I’d be better off dead. Slightly disappointed in ECT not working immediately, I came to the realization that it is not like magic, like I hoped. It will take more than one treatment to ‘fix me.’” — Subrina Singh

‘Twas the night before ECT (electroconvulsive therapy) and all through the psych ward, noises were scattered as “Despicable Me” played softly in the day room. My stomach tumbled with nerves making me question my very being. I cried, wanting to scream, wondering if it was too late to escape back home, while secretly hoping I’d die along the way. I sat there, begging God to help me calm down as I listened to hymns, mantras and old Hindi tunes.

I repeated one phrase continuously, in an effort to mitigate my anxiety. It will all be okay, I am strong and brave I tell myself. Deep down a part of me wanted to believe, that I will conquer this as I did with past obstacles. But I am scared.

[Read Related: The Hard Truths of Being Mentally ill and Indo-Caribbean]

There were times in my life when I’ve been this scared. They were when I lost loved ones. This time I am scared of losing myself. I guess that means deep down I love myself and I actually don’t want to die. Despite my self-hatred, I have chosen to fight for myself.

After suffering with a severe depressive episode and years of treatment for bipolar disorder, I made a choice to try ECT. For years I battled with medication management, hoping to find the right cocktail to treat my depression and suicidality. I did this while also joining group therapy and support groups in addition to individual therapy. In spite of all my efforts to push forward, it felt as though nothing was working. At least, it wasn’t working as much or the way I needed it.

It was then psychiatrists began labeling me as “treatment-resistant.” After numerous evaluations and consults, I was told ECT was the best chance for me to heal and have any form of recovery. I was terrified; the media had embedded this “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” image of ECT that was horrifying. Yet, I put my faith in modern psychiatry and believed in the benefits psychiatrists promised. I had no other choice. My illness had consumed me completely; it was a matter of life and death.

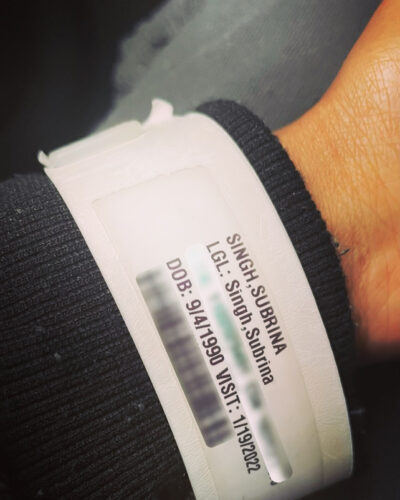

Friday, January 21, 2022, was the day it all changed. At approximately 9:45 a.m., I underwent my first ECT treatment. I cried on the short walk from the psych unit to the ECT suite. And as I fumbled to lay my body on the stretcher, tears continued to roll down my cheek. I wanted to run and scream, “I don’t want to do this.”

After multiple conversations and consultations with psychologists and psychiatrists, I knew ECT was my only viable option and my best chance at recovery. Anxiety and sadness filled my chest as the anesthesiologist carefully searched for a vein, while the psych nurse placed a blood pressure cuff on my right foot. I tried to focus on their actions as the nurse proceeded to place electrodes throughout my body and the psychiatrist stood at my head carefully applying a thick gel to my hair with electrodes on my forehead and behind my ears. Wondering how I would endure, I chanted Hanuman Chalisa under my breath.

At last, I felt the needle pierce my skin. An anesthesiologist resident placed the oxygen mask over my mouth while telling me it will be okay. They felt my anxiety as they continuously reassured me and explained the process. In a matter of seconds, I was unconscious, dreaming dreams I don’t remember.

The last thing I can recall, before dozing off, was the moment of comfort, as the anesthesiologist made an effort to calm me down, repeating the phrase, “All is well” from one of the few Bollywood movies, highlighting mental health and suicide, “3 Idiots.”

It felt like only a few seconds passed before the ECT team awakened me. “Miss Singh, you’re okay, the procedure went well,” the nurse said gently. I spent the next few hours recovering. My brain felt confused and jumbled like all the files in my brain had scattered. Other than the jaw and neck pain, I was physically okay. I was relieved, I knew the first time would be the most difficult and soon I would grow accustomed to the process.

In retrospect, it wasn’t as bad as I expected. I was overjoyed at the fact I even remembered my name. Once I passed the memory and cognitive test, I went on with my day, enjoying a deli sandwich and a Dr. Pepper.

The next day, I awoke with very intense muscle soreness. Confused and slightly concerned, I called for a nurse to come see me as I could barely sit up in my bed. After trying some Tylenol and a heat pack, I dozed off. I faded in and out, struggling with discomfort. Part of me worried if there was permanent damage but the nurses eased my worry by explaining that my body will get more adjusted to the seizure-induced during ECT, causing less soreness.

I comforted myself by wiggling my toes; they moved even though I lack the strength to pull myself up. Throughout the day, I continuously wondered if I’d be better off dead. Slightly disappointed in the ECT for not working immediately, I came to the realization that it is not like a magic as I hoped. It will take more than one treatment to “fix me.” Days later, I was still hesitant, questioning if it was too much for me. I spent most of my days on the unit crying and wishing for death, longing for a life where my suffering ceases to exist.

Night meds put me in a dead sleep. Even the 7 a.m. wake up call for vitals couldn’t disturb my sleep coma. Expecting my 9:30 a.m. call time for ECT, I forced myself to wake up. I was dying of thirst but attempted to be patient as I am NPO, meaning “nothing by mouth” and cannot eat or drink until after the procedure. I had formed a routine: slight teeth brushing, with caution not to swallow any water or toothpaste, brief enjoyment of two sips of water as I took thyroid medication and lastly placing my hospital gown on my cold skin. Now on to my regular morning routine: prayer and gratitude journal, so much to hope for and little to be grateful for. I sit patiently waiting for the nurse to come find me and take me to the ECT suite.

[Read Related: 3 Indo-Caribbean Mental Health Counselors Talk About Community’s Stigma]

Time moved slowly as I watched the minutes pass then the hour. I tried to go back to sleep but was not successful. Full of thirst and hunger, I am grateful that I snuck in that sip of water from the sink in the middle of the night. At last, the nurses approached me. Suddenly, my knees lock, filling my body with anxiety. I walked slowly to the ECT suite, carefully watching my balance. It was my third time but still, the anxiety overwhelmed me. To be honest, I was nervous about the IV needle.

As I expressed my concern, the tears appeared once again. I told the team how badly I needed to get better, as the tears rolled down my face. Closing my eyes, I waited for the sharp pain. This time I was more present, focusing on their words and my breath as I recited the Hanuman Chalisa in my head. Before I knew it, the procedure was over and I was in recovery. I drank cold apple juice and enjoyed the company of a nursing student. It wasn’t long before I was back in my unit, just in time for art. I make a conscious effort to be present while coloring. A new patient sings as we color; among the many hymns she sings, “Amazing Grace” is one of them. The words touch my heart, once again bringing tears to my eyes. I make my way back to my room, ready to clean the hardened gel from my hair.

Along the way, I laugh with a patient’s mom about the Kardashians and Orientalism. I enjoy our small talk and am eager to cathartically journal my thoughts. I do so while enjoying old Amitabh Bachchan classics and Penn Masala’s “Evolution of Bollywood,” in hopes of preserving memories. Each song is associated with a treasured memory.

Weeks passed. Days in any psych hospital are all the same. ECT, three times a week, weekends with minimal ways to pass the time and two days full of groups and therapy. By week four, I had already undergone almost 10 ECT treatments and still cried myself to sleep and awoke longing for death. Some days I even woke up from the anesthesia crying begging for death. The nurses made every attempt to comfort me but I lay there tired and defeated.

I grew hopeless and frequently expressed great concern to the psychiatrist that ECT was not working. I desperately wanted to feel better but I was trapped. Trapped in my defected brain with thoughts and voices holding me back. So much of me was already dead, all I could think was how to be rid of this life that had hurt me. I wanted to stop treatment; I wanted to give up but there was a small part of me begging myself to fight.

I had already hit rock bottom; I didn’t have much to lose so I agreed to the second round of 15 ECT treatments. Somewhere between the 16th and the 20th treatment, I began feeling better. The thoughts became more and more passive, not consuming me in the way they had before. Every time I was asked about my negative thoughts and rumination, I hesitated to answer positively. I, myself, could not believe the recurring feelings of death were vanishing. Staff began telling me I looked “brighter” and reminded me “they see it before you feel it.”

Wednesday, March 23, 2022, I had my 25th treatment. I was discharged later that day and after 64 days of inpatient, the crisp, spring air pleasantly greeted me as I soaked in the noise of the city. As I basked in the happenings around me, I sat slightly anxious in the car. What was I to expect from my life as I transitioned to this new version of myself? Even today, I do not have the answer. Part of me feels like a different person as if I’m seeing life through a whole new lens. It’s refreshing not obsessing over death. Now I can focus on thriving since I don’t have to fight to survive. I’m still sad and I still cry. I am not cured and am still very much living a life with bipolar disorder. But, the serenity I once prayed for is now settled in my heart. I took a risk for myself and it saved me. I know it’s not permanent and I understand that I will continue to cycle with depression and mania.

My ECT journey is just beginning; it is my new path of healing and with it, I believe I can reach recovery. More importantly, I’ve proven to myself that I’m worth fighting for. With this newfound will to live, I can finally live a life that is not only gratifying but teaches me to love myself.

Photo Courtesy of Subrina Singh