This post was originally published on Medium.com and is republished with permission.

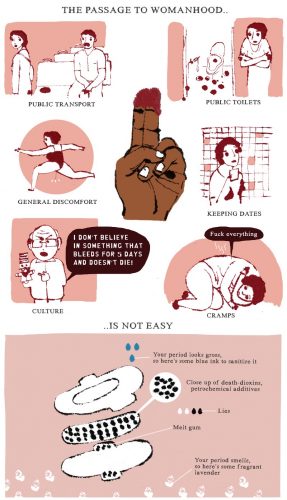

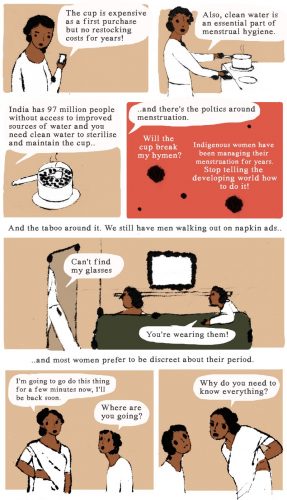

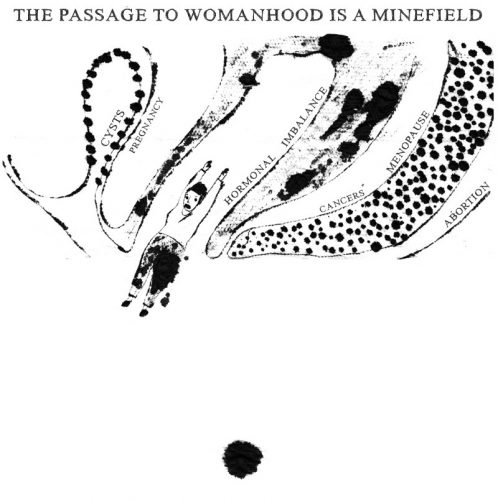

Periods suck. We spend enough on sanitary products in our lifetime to fund us a car in retirement. Sanitary products are also taxed because apparently they’re considered ‘luxuries’ and not ‘essentials.’ Right.

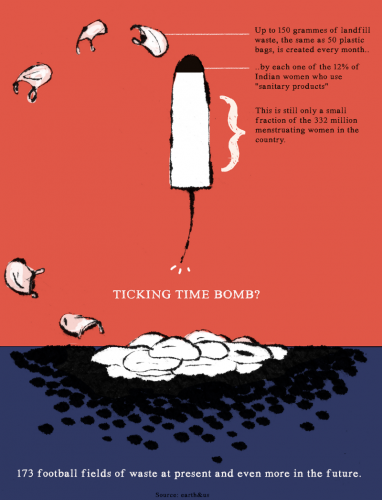

We are made to believe that we bleed blue by TV commercials and our periods are dirty and smelly, hence the multitude of products fragranced like laundry detergent. We suffer Toxic Shock Syndrome from the bleach in our tampons. We are guilty of the nonbiodegradable waste that clogs our rivers and seas.

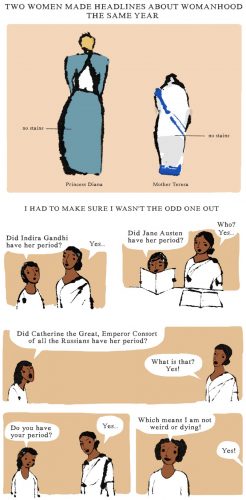

In some parts of the world, we don’t even talk about periods. Some of us are forbidden into kitchens. Others use rag cloth, ash, and various unsavoury things to plug our vaginas. Our culture creates monsters out of menstruating women.

We are nothing but emotional wrecks, conspicuous consumers of chocolate and rom-coms, unstable, bloodletting shrews who are out to destroy the world every month. We are shamed into hiding our own biology, wrapping up our essentials in paper bags, like our alcohol.

The comic ‘Green Period’ is a mix of a rant and an investigation. The rant stems from my own experiences with menstruation and the investigation has been my research into finding the most economical, green way to going red.

Aindri Chakraborty is a London based illustrator and creator of the comics blog ‘There Was A Brown Crow’. Her hand-crafted stories combine both personal narratives and current events about the subcontinent and beyond. Read more about her on her medium account.

Aindri Chakraborty is a London based illustrator and creator of the comics blog ‘There Was A Brown Crow’. Her hand-crafted stories combine both personal narratives and current events about the subcontinent and beyond. Read more about her on her medium account.