“You must be a doctor! Every Indian I have met is a doctor or engineer. You all are so smart and work so hard.”

Beaming, the woman delivered her verdict to me. I smiled at her and mused over what she said. This was not the first time I had heard this in my life and was likely not the last. But what does this stereotype mean?

In 1966, a sociologist named William Petersen coined the term “model minority” to describe Asian-Americans who had achieved success in the United States despite being marginalized and part of a minority group. He cited strong work ethic and family values as tools for this achievement. However, what is the truth and what is the myth behind this “model minority” idea?

In order to answer that question, some facts need to be presented.

In 1965, the Immigration and Nationality Act was created to limit the number of immigrants entering the US from Western hemisphere countries and open the door for more immigrants from other countries. However, the Act had stipulations: Namely, it catered to the immigration of individuals with ties already to the USA and gave preference to visa categories that focused on immigrants’ skills in areas designated as having a labor shortage.

Another caveat to this Act was the Diversity Visa. This was a lottery system in which an individual from a country with low immigration rates can apply for a visa to the USA.

Since the early days of immigration to the United States, there has been a disproportionate sampling of immigrants from Asian countries and that is reflected in the Immigration Act itself. However, the data also shows that although many immigrant groups have similar population size (e.g., Bangladeshi and Burmese), their educational, income and poverty levels vary greatly. Thus, we cannot solely cite the Immigration Act as the etiology of the differences seen.

[Read Related: The Model Minority and the Public Education System]

AAPI Data shows that educational rates, household incomes, and poverty levels vary greatly between Asian groups. Some examples are as follows.

In education, more than 70 percent of those of Indian origin holds a bachelor’s degree, whereas only 47 percent of Bangladeshi-Americans do. When this data is not disaggregated, all “Asian-Americans” are listed as having a bachelor’s degree or higher at a rate of 50 percent. In reality, many Asian-American communities, such as Burmese-Americans, the rate of bachelor degree attainment is in the 20-25 percent range.

The median annual household income for Indian-Americans in 2015 was $100,000, much higher than most Asian-American groups, and certainly higher than the national average. On the other hand, Indian-Americans have a poverty rate of 8 percent, whereas the rate for Bangladeshi-Americans is almost 25% and for Burmese-Americans, 35 percent.

One area in which all Asian groups seem to have similar outcomes is health. The MASALA study and SSATHI program suggest that South Asian-Americans have a higher risk of heart disease and diabetes than the general American population despite displaying a low risk in the traditional US risk factors. This is critical because, given the paucity of data, it is unclear how to best mitigate the poor outcomes currently seen in this group.

What does this all mean? To me, it means that there are many factors that occur when we lump people of separate countries together into having the same narrative. It does not do them justice.

The Pew and AAPI data show that there are marked differences between different Asian subgroups and even between Indians who immigrate to the USA versus those who are born in America. The etiology of the differences might not always be clear, but it is important to acknowledge them because if they are not acknowledged, many problems can be overlooked.

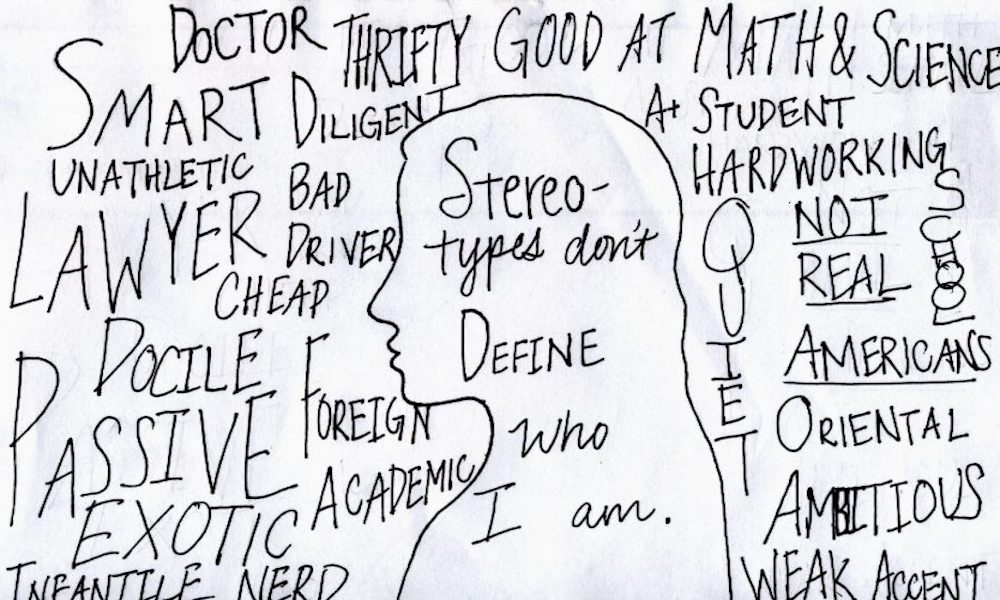

Calling a group a “model minority” can often overlook issues that minority groups face due to the minority group’s so-called ability to do “well” in America. This underscores the usefulness of data in order to analyze different facets of our world. More and more, we see examples of both “negative” and “positive” stereotyping. Neither helps the groups in question, as one can see when the data is actually examined.