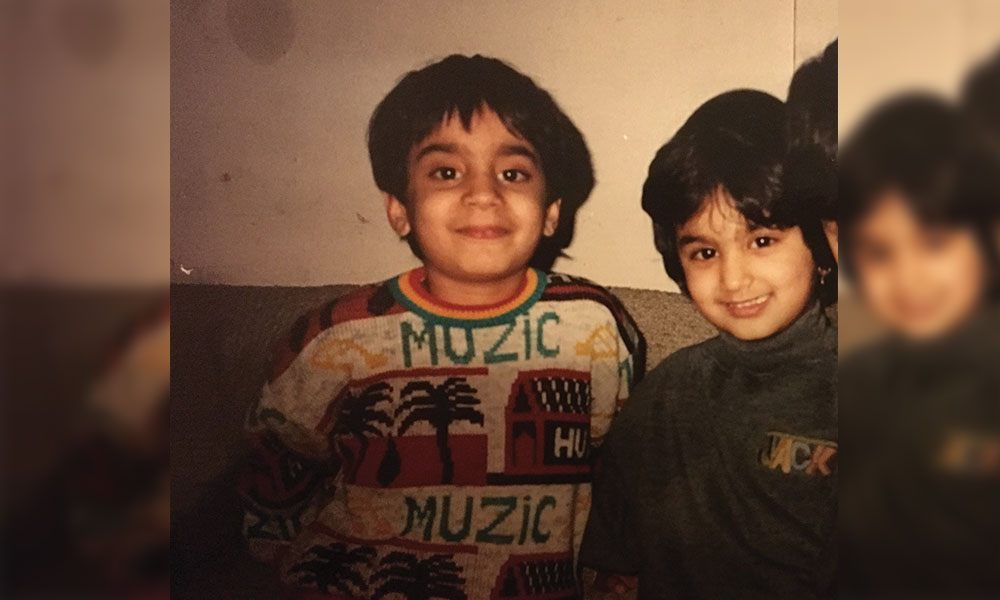

About 20 months ago, I lost my brother Ammar in a car accident. It’s been a heart-wrenching journey of soul searching and coming to terms with a reality that my best friend, the person who I could confide in about anything, the sibling I was closest to, is no longer a part of my world. Loss is something everyone goes through, and if you haven’t gone through it already, eventually you will.

In the months following my brother’s death, I received an outpouring of love, but I knew it was all temporary. The hype of the loss was only there in the beginning, and as the months marched on, it all slowly faded. I knew this would happen; I wasn’t surprised. But death can change a person entirely. People often say to me that they are astounded by the behavioral changes I’ve have gone through; they simply cannot reconcile that the Humna they knew before the April of 2016, and the Humna they knew afterward, are somehow the same person.

[Read Related: Book Review-Grief and Loss in ‘Wave’ by Sonali Deraniyagala]

I decided that I wasn’t going to let my brother’s life fade away in vain. I was going to make sure his legacy lived on, and that he would be remembered forever. And above all, I would use Ammar’s departure from this world to change everything I didn’t like about myself. I decided that I wasn’t simply going to be nice to others. I was going to offer my best self even if it required a little more effort, even if it means I have to smile when I don’t want to and if I encourage and uplift others when I’m too emotionally drained. Because truth be told, I wasn’t my best self before I lost Ammar.

It started from simple things to greater things; from making my bed every morning to starting a nonprofit. This loss still hurts, but I knew that only my best self could uphold Ammar’s legacy. Ammar was a wonderful person, more than anyone could ever realize; he always said that if you’re the best version of yourself that you could ever possibly be, life will just fall into place. He was a teacher that so many kids looked up to. He mentored kids from troubled homes of abuse while also being their teacher. He taught calculus, computer science, linear algebra, differential equations, and the Holy Qur’an. His students viewed him as more than just their teacher; they sought comfort in him. He was admired by so many and his loss is still felt by our community.

[Read Related: Surviving Suicide-A Brown Girl’s Journey Navigating Through Grief and Bipolar Disorder]

I could never even be half of the wonderful person Ammar was, but I took his principles to heart. Being my best self-was quite the effort, but Ammar was right. It worked. The Universe works in mysterious ways, but I can confirm that it actually worked. All of the wrong people slowly faded out of my life – some deliberately filtered out. The most sincere people stuck around and, astonishingly, just the right people landed in my lap.

When I pursued my mission of starting a non-profit in my brother’s honor, I was making a giant move from Texas to Arizona. There I met my lawyer, Raees Mohamed. He knew about the odds that were stacked against me and worked his tail off to materialize my brother’s legacy into a nonprofit. Shortly afterward, the two friends who stuck by my side after all of the hype surrounding my brother’s death had faded, agreed to help me in my mission. Hiba Alkhadra and Sara Bawany poured their heart and soul and proactively took on the mission as if it was their own. My web developer, whom I’ve never even met in person, Faraz Hemani, took on the project as if he had something to gain from it when he actually didn’t. I never knew that as soon as I became the best version of myself, the universe handed me the most wonderful people, who were proactively engaged in my making my dreams come true, without any incentive.

[Read related:5 Lessons I Learned From Surviving Trauma]

I’ll never have my brother back, but I now understand why he had to leave. Like I said, the universe works in mysterious ways; like clockwork, the gear on the left doesn’t touch the gear on the right, yet when it turns, the right gear also turns. Ammar had to go because in his death, a nonprofit was born that would help refugees and the underserved obtain an education. The Ammar Tariq Education Foundation reflects the same demographic of students that Ammar used to mentor. Ammar aspired to change the lives of children, those who were incredibly disadvantaged in life and refugees, for the better. I can only hope that he knows that while he didn’t get to complete his life goal during his lifetime, he was still able to achieve it.

Being your best self isn’t easy. It doesn’t mean simply asking someone how their day went. It’s asking how their day went and when they tell you they got the job, you’re more excited than they are. Being your best self isn’t just complimenting your friend’s poetry to her face. It’s bragging about her poetry to others, even when she’s not there. Being your best self isn’t just appreciating the people who work for you every time they get a task done. It’s showing them constant appreciation and not treating your relationship like a business transaction, rather, a genuine and human collaboration.

[Read related: #JusticeforFahim-Mourning my Baby Brother, Fahim]

It’s about sending a get-well text to your lawyer when he’s sick, and not being afraid to ask your web developer for homework help. It’s about going to that random girl who’s crying in the library during her finals and asking her if it’s homework you could somehow help with. It’s about picking up trash off the street even when no one is looking. Being your best self is being the change you want to see in the world, without any incentive.