by Atiya Hasan

Gone are the days that your mom would color in your period days on a calendar with red marker. As a doctor, I can’t begin to tell you how important it is to keep track of the regularity of your cycle and flow. Many times, it can be the first indicator that something may not be completely right with your body health-wise.

Technology is a huge part of all of our lives. More specifically, our cell phones play such an integral role in our everyday. They keep track of our everyday conversations, plans for the day, important reminders; so, it naturally makes sense that our cell phones help keep track of our monthly cycles as well.

When I first set out to find the perfect app, I had to go through four or five before I finally settled on one. Below, I bring you a discussion that was struck up amongst the Brown Girl staff about our favorite apps that get the job done, or at least, helps count down the days till the internal torture can end.

Period Tracker Lite

[Screenshot of Period Tracker Lite main page | Photo Source: itunes.apple.com]

Period Tracker Lite is so accurate and efficient. I can always tell when my period is coming and I love that it has features where I can document my symptoms and moods. So the next time I go see a doctor, I can talk about any irregularities (if any) since everything is right there. It’s awesome! – Nidhi Singh

I use Period tracker Lite too. Like Nidhi said it’s fairly accurate, I also like that it tells you the number of days in your cycle, and also when you’re ovulating or most fertile because it helps me to know what days during the month I need to be extra careful with protection, sorry if TMI lol. – Sana H.

Period Tracker Lite is available on Android and iPhone.

Clue Period Tracker

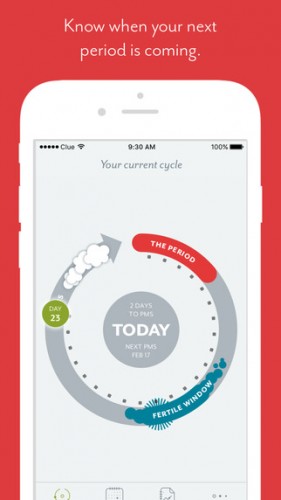

[Clue Period Tracker screenshot of main screen| Photo Source: itunes.apple.com]

Clue: simple, non-flowery design and easy interface. It includes ability to track mood, digestion, pain, etc, as well as “Cycle Science” if you’re curious about the biology behind it all. For someone who’s never had a regular cycle, it’s also been really helpful to print out a report directly from the app to discuss with my doctor. – Salwa Tareen

Clue Period Tracker is available on Android and iPhone.

Bellabeat Leaf

[Bellabeat Leaf | Photo Courtesy of Atiya Hasan]

I was actually sent the Bellabeat Leaf by the company to try out over the past six months and it’s this beautiful piece of statement jewelry that you can wear as a bracelet, necklace or simply clip on to your clothing. The app that syncs with it keeps track of steps, your period, breathing exercises, and more. The developers are constantly updating the app and making changes. It’s definitely something that I’ve added to my everyday routine. – Atiya Hasan

Bellabeat Leaf is available on Android and iPhone or follow them on Facebook for more information.

Atiya Hasan is the COO and Co-founder of Brown Girl Magazine. She currently lives in Houston, TX and is a recently graduated MD. She strongly believes in empowerment through knowledge. She is also a contributor for the anthology “Faithfully Feminist: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Feminists on Why We Stay.” In her free time, Atiya enjoys consuming large amounts of chocolate and TV shows. She also live-tweets a lot of Netflix shows @Atiyahasan05.

Atiya Hasan is the COO and Co-founder of Brown Girl Magazine. She currently lives in Houston, TX and is a recently graduated MD. She strongly believes in empowerment through knowledge. She is also a contributor for the anthology “Faithfully Feminist: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Feminists on Why We Stay.” In her free time, Atiya enjoys consuming large amounts of chocolate and TV shows. She also live-tweets a lot of Netflix shows @Atiyahasan05.