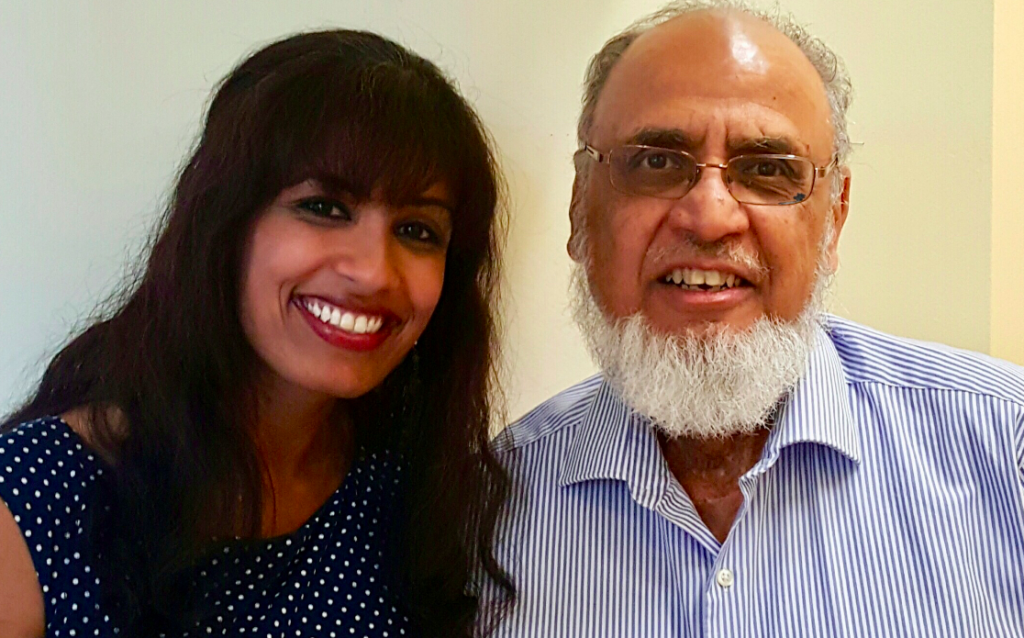

When people ask me to describe my dad, I’ve often said that he’s like the Indian version of Santa Clause. Round face, plump cheeks, white beard, and most important of all, a generous nature.

These are the qualities that have made him such a successful paediatrician in his career, qualities that are most needed in the field of oncology and haematology in which he specializes. These are also the qualities that have made him the most caring of fathers, and the most loving, respected, and looked-up-to figure in our extended family. His qualities are what have made me the daughter I am today.

Don’t get me wrong. We’ve fought as children do with their parents. I’ve made him upset. He has made me angry. We’ve often misunderstood each other, and I’ve pushed the boundaries of his comfort zone many a time. I still can remember him pacing the driveway back and forth at night, waiting for my return home, hours after my curfew passed when I was in high school. As a teenager, I did not make life easy for him.

Through it all, he loved me. He allowed me to pursue my dreams. Never interfering. Not even when he worried I might be making a mistake.

I remember him once telling me that when I left home to go to college at the University of California Santa Barbara, many people told him it would be a mistake to let me go. Not because seeking out a higher education would be a mistake—my family, grandparents, extended family have always encouraged the pursuit of higher education—but because I was an American-born girl whose parents were from India, and often he heard the rhetoric that if he allowed me to be on my own, I would become “Westernized” or “too independent.”

Needless to say, my father ignored that advice, but now at 35 years of age, when I reflect on the decision he made to allow me to go off to college on my own, away from home, I understand how much of a risk he took in doing so.

My father is the oldest of nine, and he grew up in a multigenerational household in Hyderabad, India. Traditionally, women like his sisters and cousins all lived at the family home until they were married, only then moving away.

By letting me go off to college, and subsequently never forcing me to move back home, I have come to realize how much trust he had in me that I would turn out to be a strong and morally sound woman.

Of course, we have butted heads, the topic of religion often being one of them, but he never turned his back on me. He heard me out. He supported me. He allowed me to be curious and explore the world. He had done the same when he left his home country of India in the 1960s.

Today, I work towards raising awareness on the issue of gender inequality, I look towards solutions that can end all forms of gender violence, I think of peaceful intervention. I think of generosity. I think of my father.