by Mayura Iyer

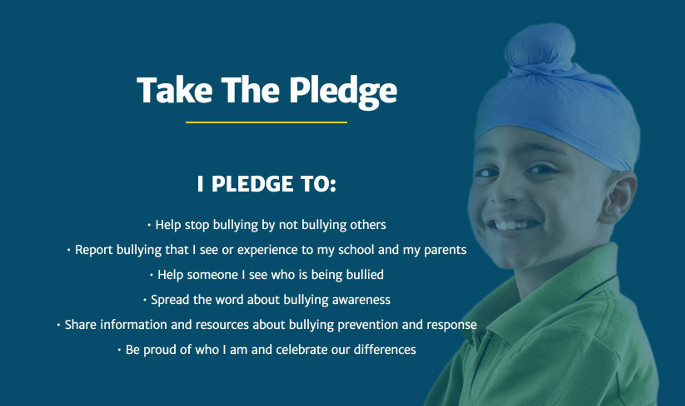

The following piece is a part of the “Act to Change” initiative, a public awareness campaign working to address bullying, specifically in the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community. The campaign website, ActToChange.org, and its social media tag #ActToChange, provide AAPI youth and community members with platforms to share their stories, engage in dialogue around bullying awareness and prevention, and “Take the Pledge” to join the #ActToChange movement.

As a proud partner of AAPI’s anti-bullying campaign, we pledge to publish stories written by Brown Girl contributors on their experiences with bullying. In addition, we will host a Twitter chat in the coming weeks to empower young adults and their families with the knowledge and tools they need to help stop and prevent bullying in our communities.

Growing up, I always felt like an outsider, like I wasn’t a real American. My black hair, my thick eyebrows, my twig legs that supported my short stature, and my dark skin stood out painfully amongst the sea of my blonde and brunette white peers.

I would be called a fob. I would be made fun of for my “weird sounding” name. I would be told to “go back to India,” despite being born and raised in the U.S.

When kids would come over my house, they would laugh at how “strange” the Indian Gods and Goddesses looked in the idols and pictures we had, and they would tease me for my parents’ accents. I felt like I had to constantly defend my Americanness to them, and deny my Indianness. Their words, their taunts, taught me at an early age to hide my culture as best as I could and to be ashamed of my heritage.

By the time I was a teenager, I had become “practically white” to my friends—a label I wore proudly. By being “practically white,” I felt like I made it—that I finally fit in. I was no longer a fob—I finally felt like a real American.

My world became split between two types of Asians—the Asians who were too Asian, and the ones who were like me. The “other” Asians were the “self-segregators,” the ones who had only other Asian friends. The ones who only listened to Bollywood Music or K-Pop, the ones who gossiped “rudely” in their native languages in front of people who couldn’t understand what they were talking about. And I was proud to not be “one of those” stereotypical Asians—the Asians who weren’t American enough.

However, when I arrived at the University of Virginia, I joined the Indian Student Association and the Asian Student Union and found myself thrown into the largest group of Asians I had ever been exposed to.

I was shocked to find that I wasn’t so different from my AAPI peers as I thought, and that I often had more in common with my Asian and South Asian friends than my non-Asian friends, despite being “practically white.”

Sure, some of them listened to Bollywood and K-Pop, and I didn’t. Some of them did speak their native languages while the only languages I knew were English and high-school Spanish. But some of them shared my love for the “Gilmore Girls” and my coffee addiction. Some of them knew all of the words to “Ignition (Remix)” by R.Kelly, just like me. Almost all of them understood my irritation with the redundancy of the phrase “chai tea.” And every single one of them was more than the stereotypes I had laid out in my mind.

As a teenager, I had navigated my world as a hyphenated person: an Indian-American, two halves of a single identity that were always separate. I always felt like I had to choose one or the other—being Indian or being American, that by embracing my undesirable racial identity as Asian that I was inherently giving up my desirable “Americanness.” And growing up, I had spent too long defending my Americanness, too long trying to fit in with the white majority, to only later give it up by embracing my “fobby” Indianness.

But having other Asian friends showed me how my perceptions of race and what it meant to be truly “American” were misguided by a world that taught me that our identities fit neatly into clearly defined boxes—a world that taught me that we were divided into clean dichotomies where if you are one thing, you couldn’t possibly be the other. It showed me that all too often, “Americanness” is equated with “whiteness,” and that I shouldn’t feel inferior as an American just because of the color of my skin.

Being involved in the AAPI community introduced me to people who I could have conversations with on race, who filled in the gaps of my black-and-white racial education that I so desperately needed. I found others that shared my struggle with my hybrid identity, others who had racist taunts hurled at them on the playground, who were teased for bringing their parents’ home-cooked food to lunch, who were called terrorists after 9/11 just because they were brown, who were stereotyped as being “good at math” and made to feel inadequate when they weren’t, who were made to feel ostracized and un-American when expressing parts of their heritage.

I realized how the stereotypes that led others to call me a fob were the stereotypes I was reinforcing by refusing to accept the other half of my identity—that in my desperation to be accepted, I was widening the racial gap that had hurt me as a child.

Having other Asian friends illuminated the socially constructed racial dynamics around me, and deconstructed my own ignorance to these issues. It has taught me to refuse to be pigeon-holed by the perceptions of what society thinks being Indian or being Asian means. Being a South Asian-American doesn’t fit neatly into any preconceived notions you might have. It isn’t a clean dichotomy the two, but it isn’t about choosing between two halves of a hyphenated identity—it is an interaction that is as nuanced and complex as each of our individual identities.

If being involved in the AAPI community has taught me anything, it has taught me that by embracing my Indianness, I am not sacrificing any of my Americanness.

You can call me one of those “other” Asians. You can pin your stereotypes on me and make your assumptions about my identity. You can call me a “self-segregator,” a fob, or whatever other names you can think of. But you cannot deny my identity as an American.

[Feature Image Photo Courtesy: AAPI’s “Act to Change” campaign]

Mayura Iyer is a graduate of the University of Virginia and is presently pursuing a Master of Public Policy. She hopes to use her policy knowledge and love of writing to change the world. She is particularly interested in the dynamics of race in the Asian-American community, domestic violence, mental wellness, and education policy. Her caffeine-fueled pieces have also appeared in Literally, Darling, BlogHer, and Mic.com.

Mayura Iyer is a graduate of the University of Virginia and is presently pursuing a Master of Public Policy. She hopes to use her policy knowledge and love of writing to change the world. She is particularly interested in the dynamics of race in the Asian-American community, domestic violence, mental wellness, and education policy. Her caffeine-fueled pieces have also appeared in Literally, Darling, BlogHer, and Mic.com.