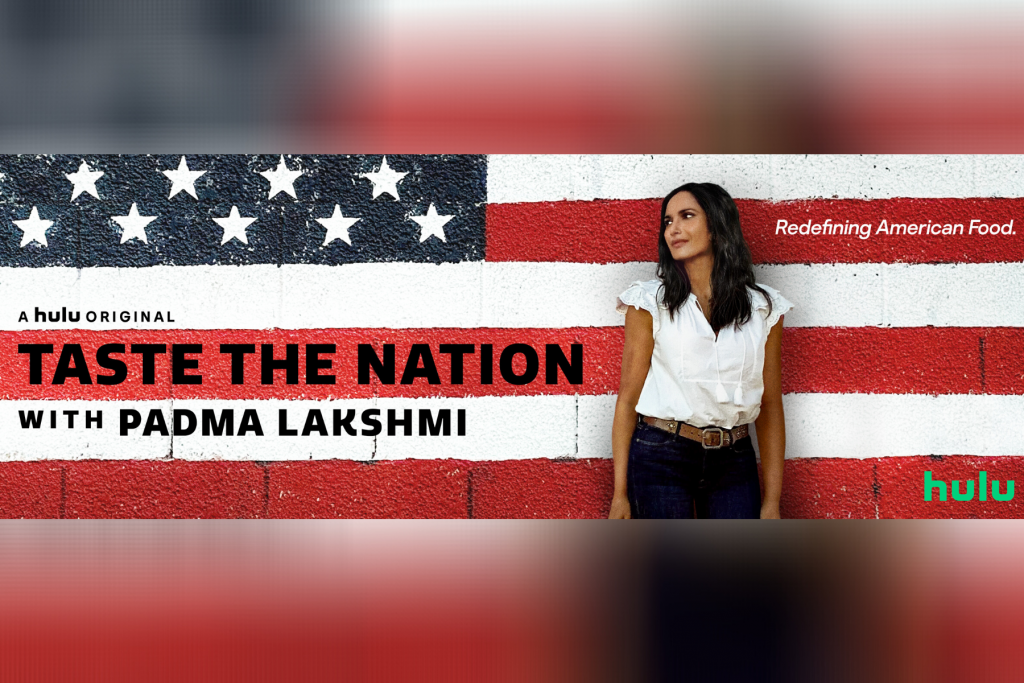

[Featured Image Courtesy of Kevin Murphy/Hulu]

What exactly is American food?

When you think about the answer to that question, hotdogs, hamburgers, and French fries may come to mind. However, author, actress, and TV host Padma Lakshmi has set out on a mission to prove that American food is much, much more than that. In her new Hulu series, “Taste the Nation,” Lakshmi tours the country, exploring various ethnic cuisines and cultures that make the nation what it is, that redefine what American food is. From conception to the small screen, Brown Girl contributor Tina Lapsia asked Lakshmi about her experience and journey creating “Taste the Nation.”

How did you come up with the concept for “Taste the Nation?” Why now?

“Taste the Nation” came about as a direct result of my work on immigration issues with the ACLU. I wanted to amplify the voices of other immigrants or indigenous people who get vilified by our current administration.

How did you decide to go to the locations you chose? Why and how did you pick the cuisines and cultures that you did?

I wanted to show a good cross section of the different communities living across the United States. In this first season we obviously couldn’t showcase every culture that we wanted to, but we wanted an accurate representation of what America looks like right now. Many people love tacos or Pad Thai, but don’t often think about the hands that make their takeout. We wanted a balance of Asian and Latin cultures, as well as some older, more established ones, and also newer immigrant communities, too.

I thought it was quite relevant and poignant to start off the series in El Paso, TX and interweave discussions about border politics and what’s happening in Washington, D.C. Was putting that as the first episode intentional? Is there a reason the episodes are in the order seen?

We did not know the order in which the episodes would be arranged when filming. At that time, we were consumed with the themes of each episode — which are different from one another. The order of the episodes was a collaborative effort between me and my producing partner, and Hulu. You can jump around in whichever order interests you: we just wanted there to be an established flow — these are just our suggestions!

“Taste the Nation” is being released at a historical, stressful, and momentous time in our nation. How do you think the series fits into the country’s narrative and what’s going on right now?

I could have never imagined that the show would be released during such a tumultuous and painful time in our nation; there would have been no way to predict that. But I’m extremely proud that my team and I address many of the issues that have been bubbling up in our culture.

The very reason I did “Taste the Nation” is because I felt there was a lack of representation of the stories of many Americans, and that the stories of BIPOC people were not being given the platform that they rightfully deserve. I wanted to use my platform and my power as a filmmaker to address this issue because it is an issue that I have been dealing with my whole life. I am a brown woman working and living in a white man’s world. So of course that influences my point of view. And I take full responsibility for the fact that this show is completely, subjectively based on my POV. It is informed by my personal experience and born out of a genuine hunger to learn, understand, and celebrate the many contributions of immigrants across generations of people who have come and settled here. Early in my career, I was very frustrated that people in power weren’t interested in my existence. Now that I have some power in the media, I want to prove that many of us are indeed very interested, and that there is an audience for all of our stories.

On that note, one of the concepts that stood out to me from the El Paso episode was “food as resistance.” What does that mean to you?

Using food as resistance means insisting on eating traditional foods of a community, rather than commodity food that is dictated to us by the commercial food establishment. Those foods are often given to us because of the continued influence of colonialism. A great example of this is the notion of corn tortillas versus flour tortillas. Flour was brought here by European colonialists. It is also what’s used to make fry bread, a food item that many Native Americans now reject on principle because of what it signifies and its attachment to the genocide perpetrated by the American government of indigenous communities.

I especially loved the episode where you explore your heritage and upbringing in Jackson Heights and the showcasing of South Asian food. You ask Madhur Jaffrey, “Why hasn’t Indian food had its big moment in the West?” What is your answer to that question?

I think that Indian food is gaining traction on both coasts of our country. I think there are people making amazing Indian food in the middle of the country too, like Maneet Chauhan, for example. While the Indian American population is growing, we are still a smaller, if mighty minority (in sheer numbers, compared to say, Mexicans or other immigrant groups). I think a lack of easy availability of fresh ingredients like curry leaves and tamarind have to do with this as well, but I’m hopeful that the Kati roll will continue to proliferate among college campuses. In my neighborhood, near NYU, it seems that’s all college students eat.

Padma Lakshmi and DJ Rekha in Jackson Heights, Queens, NY. [Video Courtesy of Hulu.]

What was your favorite “Taste the Nation” episode to film and why?

My favorite episode to film was the Thai episode, because Lotus of Siam has always been, in my mind, one of the best restaurants in the country. But more than that, I was excited to do a female-centric episode and hear from their [the Thai women’s] perspective what it was like to come to the United States when they didn’t know the language or culture well at all. It gave me immense pleasure to highlight the story of how American in-laws embraced these foreign brides their sons brought back. It allowed me to show that America does have a history of being welcoming to immigrants. I wanted to remind the current administration, I suppose, that there is another way. One born not of hate, but of love and genuine curiosity about another person’s culture.

How do you see the restaurant industry changing or evolving in light of COVID-19? What advice do you have for South Asian businesses in the industry in particular?

I think restaurants will almost have to be reborn, like a phoenix rising from the ashes, because of the havoc COVID-19 is wreaking on the industry. I think that to survive in the restaurant business post-COVID, South Asian restaurateurs will have to lean in to the regionality and diversity of Indian food. We don’t need another Balti cuisine restaurant. There’s so much more to Indian food than Saag Paneer. I think one way to stand out is by highlighting the beautiful vegetarian specialties of Gujarati cuisine, for example, especially for the number of people who are becoming vegan. I would love to see an Indian restaurant that specializes just in seafood from our coastal areas, in the way that Marea specializes in coastal Italian seafood. I think specificity will play a large roll in differentiating from the pack.

The episode about the Gullah Geechee people was particularly eye-opening. How can people not part of the community support and sustain such minority food cultures and ecosystems?

To start, I’m very happy to share the following link for the organic farm of Bill & Sará Green that we feature on that episode so that anyone can support their great work. In general, I think focusing more attention on “mom and pop” businesses will not only help get the restaurant industry back on its feet, but also allow people to expand their own personal food knowledge. Be adventurous, try new cuisine. Support women-led businesses as well; they often don’t get the same attention male chefs do. Additionally, in our social media culture, restaurants gain popularity through Instagram and word of mouth. If you like your experience at one, be vocal. Share that on your platforms so other people in your respective communities can support them as well.

Is there anything else you’d like to share with our readers about “Taste the Nation?”

I hope that young brown women will enjoy watching this show and the fact that it was made as a love letter to this new generation of brown girls so that they could hear a different narrative than the one I was fed when I was a young woman coming up in the world. If you do like it, I hope you will help me spread the word because we need more shows like this that tell our stories, by our people.

I am so happy that an outlet like Brown Girl Magazine exists and I wish there had been something like this for me as a young person. It would have gone a long way towards giving me the self-confidence that I had to earn the hard way through my formative years.

“Taste the Nation” premieres on Hulu on June 18.

View this post on Instagram

*This interview has been edited for clarity.