[Thanksgiving table in author’s home/Photo Courtesy: Elizabeth Jaikaran]

[Thanksgiving table in author’s home/Photo Courtesy: Elizabeth Jaikaran]

There are very few Americans who are unaware of the fact that their homes stand upon land stolen from this country’s indigenous peoples. It is a shameful and known truth, even for immigrants who arrived on this soil centuries after this tragic imperial genocide was perpetrated in the name of colonial resettlement.

To add insult to grave injury, our educational systems have reclaimed this narrative by glorifying European settlers and reducing the culture and lived experiences of Native Americans to slender chapters in our history textbooks that are more indicative of ancient societies which have since dispersed, rather than of struggling communities who continue to resist in the margins.

[Read Related: 3 Masalafied Recipes for Thanksgiving Sides]

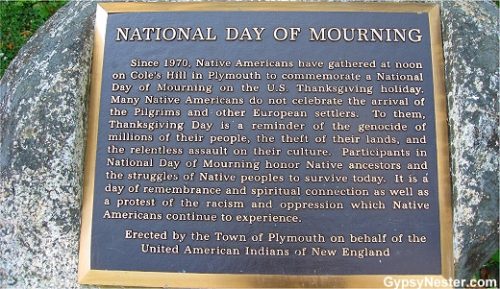

While, admittedly, Thanksgiving does not blatantly equate to the perverse celebration of the genocide and displacement of America’s indigenous peoples, it is representative of a celebration that is sinister nonetheless: revisionist history. It is a holiday that abruptly ends the historical narrative with a cut screen to a joyous meal shared between the Native Americans and the Europeans, and runs the credits without acknowledging the horrors that took place thereafter. It is a convenient way of avoiding discussion of the horrors that we already know about. While this intentional myopia is celebrated each year as a national holiday by millions of Americans, each year many Native Americans observe Thanksgiving as a day of mourning, with the joyous feast we venerate serving as their proverbial last supper.

[National Day of Mourning plaque located at Cole’s Hill in Plymouth/Photo Source: Pinterest]

[National Day of Mourning plaque located at Cole’s Hill in Plymouth/Photo Source: Pinterest]

Among the historically aware of the nonetheless celebrating populous—those who recognize Thanksgiving’s revisionist conditioning—are the inevitable apologists. They are the defenders of the observance of the autumn feast as simply a time to get together with loved ones and reflect on all the things for which we are thankful. To be fair, for many Americans, especially immigrants, the holiday really is as simple as that. It is an appreciated and highly anticipated day off from work and school during which they can gather with loved ones and reflect. Often, this is the only day when many families are able to get together in this way out of the entire year. To be just, however, the pursuit of togetherness and thankfulness is not a more deserving priority than standing in solidarity with our native countrymen who weep while we feast.

Contrary to the intuition that groups who have endured struggles and injustice would more easily recognize and empathize with the plights of Native Americans, bringing this reality to resonance is generally a difficult feat for immigrant communities. In fact, there is a fluid phenomenon throughout immigrant communities whereby newfound economic opportunities effectively silence any criticism of the American politico on the immigrant tongue. That is, both the promise and the actualization of social mobility is enough for many immigrant communities to disregard the past and ongoing struggles of other disenfranchised groups, including Native Americans. Money is often sufficient to beckon willful blindness among those who have never seen these financial opportunities before.

[Read Related: First-Generation Immigrants: Why It’s Okay To Pick And Choose Your Culture]

For South Asian and South Asian Diaspora immigrants, this is a far more peculiar phenomenon given that if not for Columbus’ pitiful navigational propensities, the subcontinent would have been the recipient of the very imperial murder and ongoing injustice that has fundamentally disrupted Native American existence. In addition to Thanksgiving apologists, there are even Columbus apologists who cite the fraudulent discoverer favorably as, without him, America would not exist as it does today. Indeed, the semblance of financial stability and democracy are even enough to beckon the glorification of a man who bragged about serving indigenous infants as dog food.

Even without contributing to these painfully flawed narratives (and despite how othered many immigrant communities may feel within the national landscape) these communities are joined with the majority in their complicity of normalizing Native American exploitation and abuse via their silence in a discourse which begs for their voices, and their subscription to harmful revisionist history. Acknowledgment of our role, even if completely passive, in Native American disenfranchisement is a crucial and necessary examination that is seldom undertaken and ultimately perpetuates their oppression and adversity. The time is appropriate to discuss the cost of our privileges.

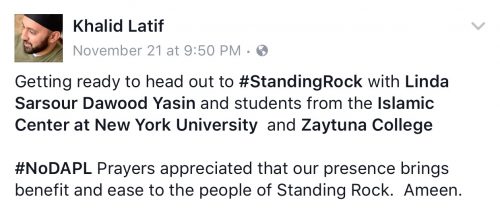

This year, the juxtaposition of Native American suffering and the general American celebration of Thanksgiving was especially striking, as the Sioux tribe of the Standing Rock Reservation protested for their right to clean water while we lined our tables, hearts filled with thanks, with all varieties of food and drink. The protests at Standing Rock have endured for months—and, aside from the modern day Plymouth-reminiscent opportunists who have treated Standing Rock as a music festival/cultural adventure of some sort, the protests at Standing Rock have overall illustrated the great power of solidarity and showing up for the interests of others. On Thanksgiving Day alone, everyone from Black Lives Matter to NYU’s Islamic Center joined the resistance as water protectors. Accordingly, the time is increasingly poignant for collective reflection with respect to the price of our thankfulness and the symbolism of Thanksgiving.

[NYU’s Muslim Chaplain before embarking to Standing Rock for Thanksgiving weekend/Facebook]

[NYU’s Muslim Chaplain before embarking to Standing Rock for Thanksgiving weekend/Facebook]

This kind of reflection summons discourse that is rife with questions and deficient in answers. What would optimal solidarity look like? What should it look like? Does it call for a revocation of the holiday altogether? Should we wipe it from the calendar and return to work and school as regularly scheduled? Sacrificing our day of togetherness to show support for those who hold the day as one of mourning and devastation? Or is a thorough rebranding of the holiday from the flowery Pilgrim-Native American narrative to one of unfettered honesty and reverence for indigenous peoples more ideal? Should we turn it into a day of joint mourning? Or would that be overstepping our involvement in their lived experiences?

At the very least, curricula throughout the country should be updated to reflect the salient reality of Native American suffering. But with respect to Thanksgiving Day, does solidarity mean we must end this long tradition of gathering with loved ones, or should it mean that we incite a new era of gathering together for a renewed purpose? Perhaps, now, we should gather for sobering introspection? How can the national consciousness be moved in either direction?

Despite these abundant questions that have, surely, been posited many times over the past decades, it is staunchly clear that the pursuit of solidarity is one to which all non-Natives have a duty to subscribe as we continue to live in a country that has sprung from indigenous flesh.

The growing solidarity at Standing Rock this Thanksgiving showed that the national consciousness is, in fact, willing to disrupt their comfortable traditions by no longer allowing Native Americans to grieve alone. Though perennially late as allies, the opportunity to do better is clearly open. We just have to start answering some very difficult questions.

Elizabeth Jaikaran is a freelance writer based in New York. She graduated from The City College of New York with her B.A. in 2012, and from New York University School of Law in 2016. She is interested in theories of gender politics and enjoys exploring the intersection of international law and social consciousness. When she’s not writing, she enjoys celebrating small joys with her friends and binge watching juicy serial dramas with her husband. Her first book, “Trauma,” will be published by Shanti Arts in 2017.

Elizabeth Jaikaran is a freelance writer based in New York. She graduated from The City College of New York with her B.A. in 2012, and from New York University School of Law in 2016. She is interested in theories of gender politics and enjoys exploring the intersection of international law and social consciousness. When she’s not writing, she enjoys celebrating small joys with her friends and binge watching juicy serial dramas with her husband. Her first book, “Trauma,” will be published by Shanti Arts in 2017.