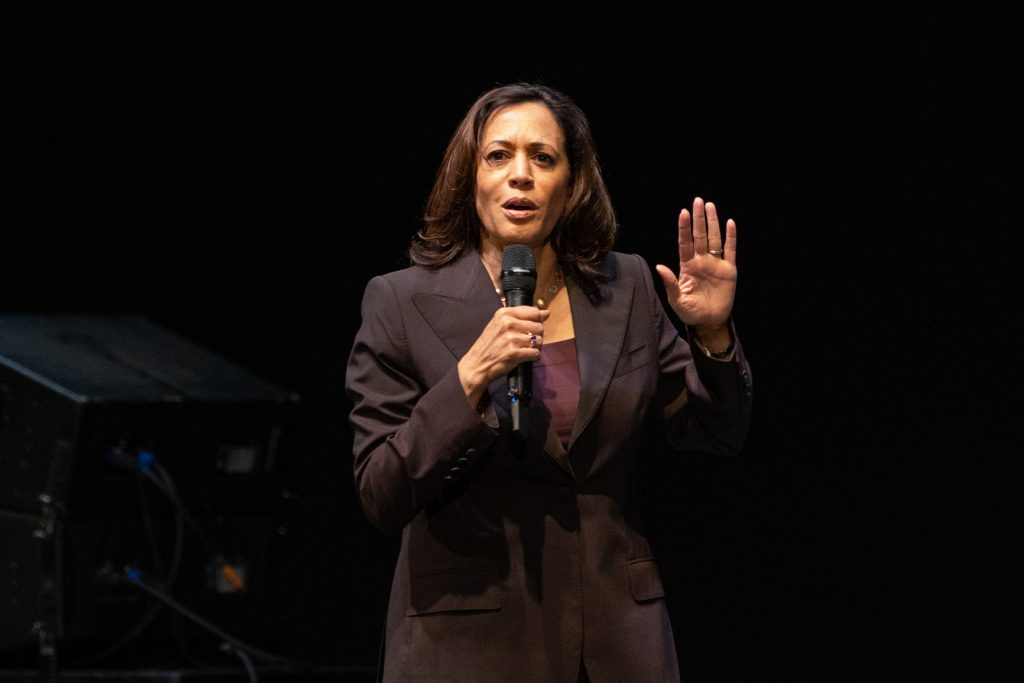

Featured Image Credit: Shutterstock

As a child of first-generation Indian immigrants, I am aware of the weight that names carry and their connection to people’s identity. Recently, Fox News’ Tucker Carlson repeatedly mispronounced vice-presidential candidate Kamala Harris’ name, replying “whatever” to a guest who corrected him. That seemingly small TV moment triggered many children of immigrants because we have heard and seen it before. We know that when a public personality unapologetically mispronounces a name and then voices their offense at being asked to open up their world view, our own experiences are painfully dredged up.

We experience an all-too-familiar discomfort of being pushed into “other,” not of this country, not of this place. Harris’ name, Kamala Devi Harris, is but one representation of that “otherness.”

Remarks like those from Carlson bring us back to the countless times when we acquiesced to someone who was too bothered to learn how to say our names. In fact, there is a presumptive, albeit unfair, notion that the majority of Americans never learn how to say or spell seemingly complex non-Anglo names. So, we preempt conversations by anglicizing our names: Ajay becomes AJ, Shailaja becomes Shelly. We trade in arguably the largest part of our identity to fabricate comfort for others, and, by doing so, acknowledge our “otherness.”

Growing up, I had too often submitted to the strangers behind the DMV counter who called me out of line with “Gandhi,” not bothering to use my full last name, “Ghandikota.” I, too, traded in the exhausting onus of correcting and teaching for the convenience of getting a task done or getting out of an uncomfortable moment expeditiously.

My husband, also Indian, abbreviated his name from Nikhil to Nik when growing up in New Jersey. His high school guidance counselor convinced him that no one would read a resume from a “Nikhil.” Some teachers would call him Ni-Hi. To avoid embarrassment, at roll call, he would cut those teachers off with “just call me Nik.” Today, he still recounts with remorse and anxiety the times he had to choose between his given name and the name that would allow him to fit in. Swap Nikhil with Ashoka, Malini, or Anjali, and you’ll hear the same story.

[Read Related: Say Your Name, Your Real Name: my Back-to-School Advice for Roll Call]

What’s in a name? Everything. Names are bound in genealogy, aspirations, and virtues. Given names carry great weight in so many communities around the world, including the Indian community. Many Hindu names are chosen with careful deliberation, as zodiac and genealogy charts are consulted by high priests and naming ceremonies are considered sacred. Kamala meaning “lotus” and Devi meaning “goddess” was clearly no accidental selection for a future political rising star, and, I venture to guess, is consequential for Harris. That’s enough of a reason for us to learn how to say it right.

Until Harris arrived on the national ticket, America, arguably, had little need to reckon with non-Anglo names in politics. As the only two governors of Indian descent, former Ambassador to the UN and Governor Nikki Haley and former Governor Bobby Jindal–born Nimrata and Piyush, respectively–have publicly renounced various elements of their South Asian identities. I don’t advocate discrediting members of our community for the decisions they feel compelled to make to be more accepted professionally. I also can’t ignore the inevitable conclusions the next generation are often forced to arrive at– their “Asian-ness,” by name and color, is too soon, too much, too different.

As Harris took the convention stage as the Democratic VP candidate, she reminded us of three things as it relates to the “other” syndrome. She catapulted to the national stage the name of a relatively unknown figure, Shyamala Gopalan. In recalling her South Indian mother and her influence, she, in effect, reminded us that identity and platform cannot be separated. She also boldly claimed her biracial Jamaican and Indian heritage, not succumbing to the pressure to choose one over the other, demonstrating to us that America does not have to choose either.

As she acknowledged her love for her “chitthis” (a South Indian term for aunties), she was creating a space to normalize language that may seem different for many and very normal to her. And, finally, as a person of consequence, she demonstrated to us that anyone can be taught. Indeed, as I hear Kamala’s name (Kuh-mah-lah) spoken correctly at the Democratic National Convention by former presidents and sitting senators, I hear my mother’s voice, as she used to say, “if people can pronounce Schwarzenegger and Tchaikovsky, they can surely say your name.”

We are human. We make mistakes. But let us all show interest and demonstrate effort by researching and asking for clarification when we are confronted with a name we can’t spell or pronounce. Let us also be persistent in ensuring our names and identities are showcased in the way they were intended to be so that the Ameyas, Kirans, and Sangeetas of the future can take the stage confident in their belonging.