A few weeks ago, sitting in a packed theater in Seattle, WA, Rupi Kaur led me through one serious emotional journey. I could feel my body waking up to the words of “how we make up.” As she explained “unibrow,” I was transported back to an almost identical conversation I had with my own younger brother 15 years prior. I had to close my eyes as my own experiences with self-harm were reflected back at me during “self-hate.” And as she recited “broken english,” I was brought to tears by getting the clearest picture I’ve ever had of my immigrant mother’s extraordinary life. In these ways and so many others, Rupi is me.

In recent years, I’ve found myself more frequently reflecting on the multiple different aspects of my own identity. I am an American citizen by birth, a fact that feels so mundane that I rarely see the worth in mentioning it. I’ve also lived in predominantly white environments my entire life and surrounded myself with white friends who accepted my different skin tone with such ease that I rarely acknowledged my “otherness.” In many ways, I can relate more to white people I’ve never met than I can to my own first cousins, my flesh and blood, who grew up in India. Finally, as a teenager and in my early 20s, being a woman felt like the most important part of my identity, and as such, I identified with so many representations of young female experiences reflected back at me from the stage and screen. But there have always been limits to these representations – the image is no longer a full, accurate reflection of me, but of the white girl sitting next to me. And try as I might, I simply can’t relate. I wonder now if, at some point, I tacitly accepted that those limits would always exist, that parts of me weren’t worthy of representation in popular culture, and as a coping mechanism, I downplayed the importance of my cultural identity to myself.

I would like to be able to say that I am loud and proud to be brown. It’s usually quite the opposite. Many times in my life, I wished for the ability to crawl into my skin like a cocoon and butterfly—exit as a basic white girl. I even frequently asked my mother in frustration why she couldn’t cook chicken pot pie instead of aloo gobi with an odor so strong our neighbors could smell it. But after watching an auditorium full of white and black and Hispanic and East Asian women embrace and cheer for an artist who looks so much like me, I left that theater wearing my color like a badge of honor. For one of the first times in my life, I was proud of what my skin tone communicated to the people around me. I understood all of the implications of Rupi’s references to Punjab and Bollywood and Deepika Padukone. And I was not confused about the meaning behind her words, because I am intimately familiar with her experiences. They are my experiences, and the experiences of so many other brown females in America and Canada.

Once I let myself fully acknowledge this part of myself, it wasn’t hard to see how beautiful it truly is. I grew up watching Bollywood movies, subconsciously learning my parents’ native Hindi, and dressing up in lehengas for community weddings. I watched in horror as my parents mispronounced words like “adolescence” and “metabolism” and “pentagon” as they prepared for college lectures. I spent weeks in India during summer breaks fighting off mosquitos and drinking water from freshly opened plastic bottles. I even felt shame walking into a fraternity house my freshman year of college with my new Indian Student Association friend group and hearing two drunk white boys wonder aloud at “who invited all the brown people.” All of these experiences have added depth and color to my life, even when I have resisted them, even when I pretend some of them never happened. Only recently, through the eyes of peers and contemporaries like Rupi, have I begun to truly embrace these parts of me, to see how these ties that I tried to keep buried bind me so strongly and intimately to thousands of women.

To be fair, there are limits to how much of myself I can see in Rupi. I cannot, for example, relate directly to her experiences as an immigrant and as a Sikh, as the eldest child, a Canadian, and a poet, and most definitely as someone who can talk about her sexuality in front of her parents (seriously, nerves of steel). But these differences do not create a barrier to understanding her upbringing, her values, or her struggle with cultural identity. Instead, these differences serve to enhance both my understanding of myself and the Western world’s perception of what it means to be brown. We do not all fit into one bucket. We are not all quiet girls waiting at home for our parents to arrange our marriage or while our husbands make a living as doctors, taxi drivers, engineers, and hotel owners.

My generation of South Asian women is fighting against these stereotypes to define ourselves, to give ourselves representation on stages that reach audiences of all colors, so that we can start to distinguish ourselves from one another to undiscerning eyes. The most notable recent examples for me are Mindy Kaling and Priyanka Chopra. Seeing desi women star in American TV shows was, in every cliché way, such a breath of fresh air. But I probably have even less in common with Mindy and Priyanka than with Rupi, and it’s not fair to pin the hopes and dreams of diasporic representation on one or two people. There is an emergence of more and more brown female artists, with each new face and personality reinforcing the truth that I have subconsciously known for so long: that we are all beautiful, that we are all unique, and that the color of our skin defines only a portion of who each of us is as an individual.

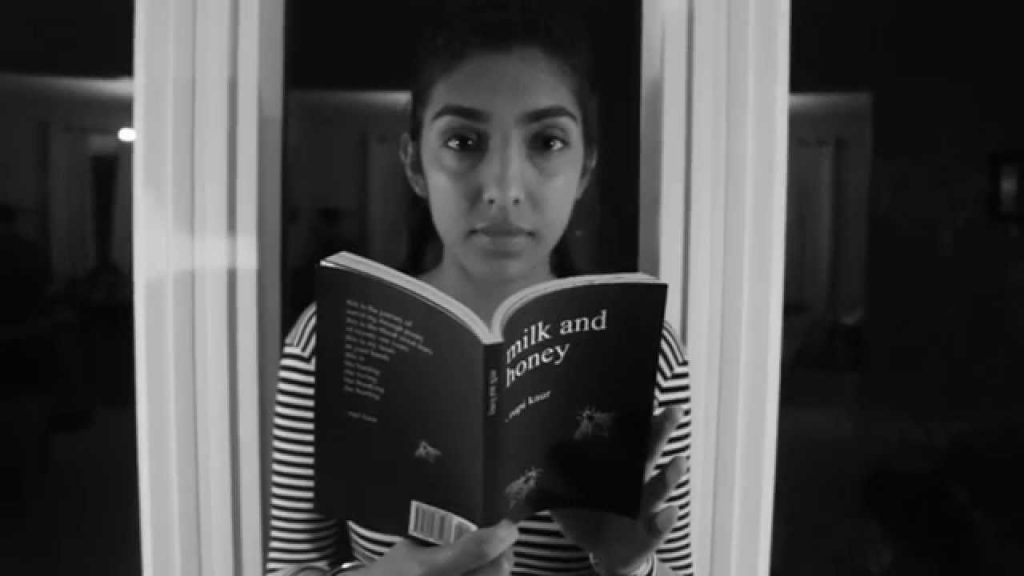

I am someone whose opinions about dating within her own race have gone back and forth, who had to balance having the quintessential American high school and college experiences with meeting the expectations of her parents’ culture, and who tries to blend in with peers’ personalities and wardrobes, but flaunts her brown-ness when it’s most convenient and appealing to be “different.” I’ve recently come to the realization that I will never have one clear path or a definite, permanent answer to “who am I” and “what am I,” questions that any immigrant or child and grandchild of an immigrant will inevitably ask themselves. All I can do is look for any hints and clues that I’m not wrong to be confused, not alone in wondering how to define my self-worth, and not misguided to be so proud of my cultural identity. Rupi’s words are full of these signs, and I plan to read them over and over again for years to come.