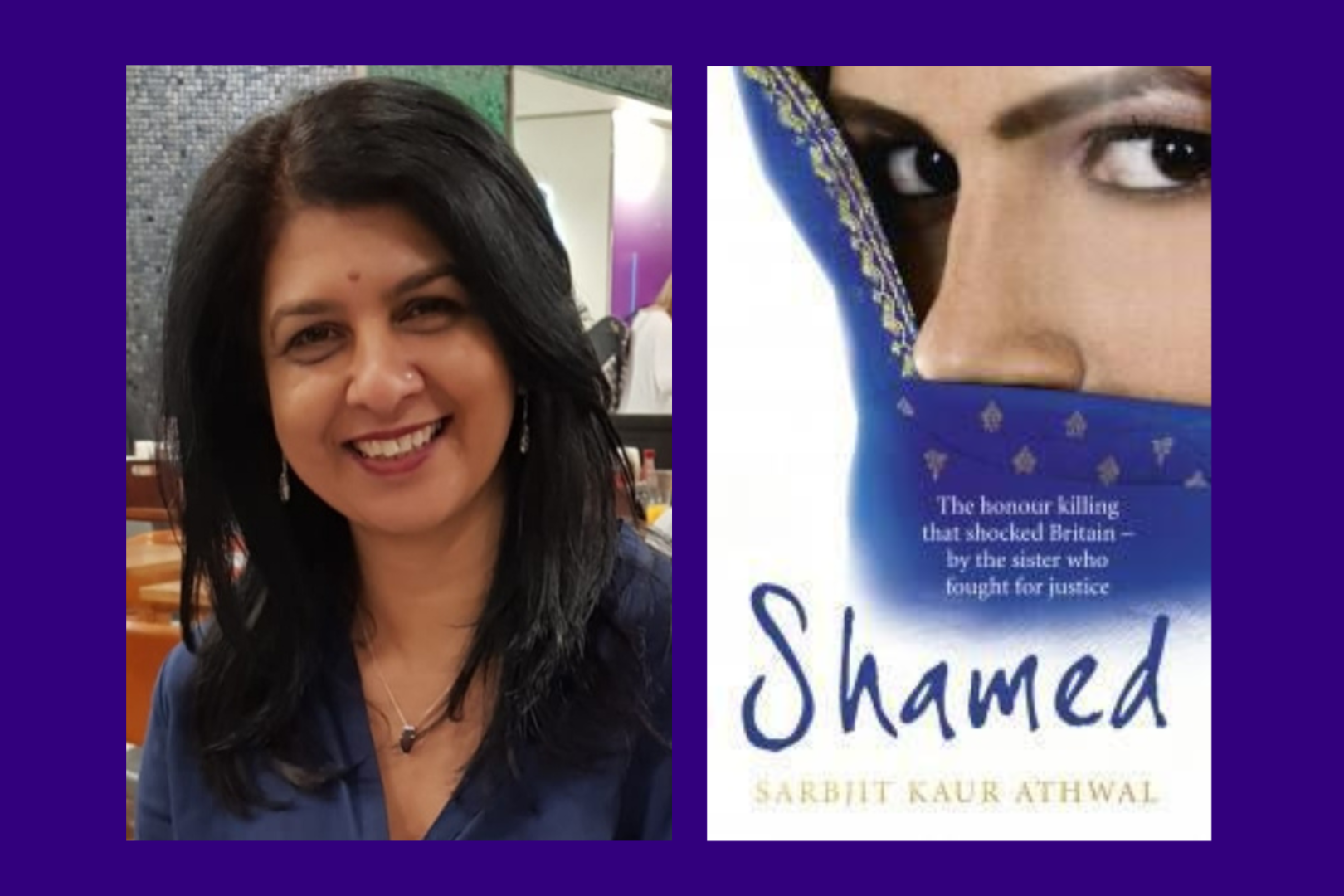

Choice and consent. Words that I subconsciously take for granted and exercise every day — whilst for many this remains a privilege to even have or simply recognise it as their right. Shame is a burden that lies heavy on our shoulders when a choice is eventually made, much to the dismay and scrutiny of others. When British South Asian Sarbjit Kaur Athwal chose her right to fight the patriarchy and speak her truth against gender violence, the aftermath that followed will leave many reeling.

“Shamed” is Athwal’s journey of the price for saying “No” to honour-based violence — the title of her book aptly speaks volumes. At the mere age of 19, she was married into a strict Sikh family. Her marital household also consisted of her father-in-law, mother-in-law, her brother-in-law and his wife. Raised within a conservative family, it had been ingrained in Athwal’s mind to obey her seniors and maintain family honour at all costs. Despite both daughters-in-law being treated no better than servants by their in-laws, with their every move controlled, it was still deemed as Athwal’s and her sister-in-law’s responsibility to ensure the family remained as a joint unit.

It was Surjit, Athwal’s sister-in-law, whilst merely standing up for herself, who was often beaten for being perceived as “disobedient.” Finally, she decided she wanted to eventually leave her marriage — a decision which cut her life short. In the name of so-called family honour, Surjit was tricked into a family wedding in India and never returned. Sarbjit soon discovered that her mother-in-law had masterminded Surjit’s murder and dumped her body into a river.

[Read Related: Op Ed: Murdered British Asian Sabina Nessa Deserves Louder Voices]

The fight for justice for Surjit was complex, and lengthy and met with systematic failures from the police, medical services and the local community. Sarbjit’s decision to stand up for herself and her late sister-in-law by testifying against her in-laws and her husband was met with disapproval from faith members and other close relatives and friends.

I used to go to the gurudwara (Sikh temple) and the faith leaders would tell me how I should be treating my mother in law as my own mother, despite the atrocities of what she had done. When I did try to leave many times, I had to think about the family honour. I was made to believe I was in the wrong. I was made to believe by professionals that I was mentally unstable.

Years on, when evidence came to light, she went behind her husband’s back, whilst suffering from a life-and-death illness in hospital, and worked hard to put all the missing links of the lead-up to the murder. Finally, her testimony ensured that her husband’s mother and brother were prosecuted for Surjit’s murder.

View this post on Instagram

Having moved on from her frightful past, Athwal was determined to do more for women who were still trapped in forced or abusive marriages. She realised that within the police force, there was a lack of awareness and cultural understanding when dealing with honour-based crimes. In 2012 she joined the Metropolitan Police Service and worked with the police where she helped many other honour-based victims come forward and then founded the charity True Honour.

On 12 November 2022, along with other survivors of gender violence, the Pearl Project Awards at Kingsgate Church in London, will be recognising and championing survivors like Sarbjit and the work they continue to do to empower others. Sarah Clay, CEO of Voices of Hope, said:

We want to champion survivors within our community, highlighting the challenges they face during and after abuse, alongside telling their inspiring stories of survival, restoration and triumph which will undoubtedly bring hope to other women and raise awareness of the prolific issue of gender based violence. Why pearls? Pearls form when a foreign substance, like sand, slips into an oyster, causing an irritation. The oyster secretes a fluid, called nacre, to coat the irritant. Layer upon layer of this coating is deposited on the irritant. Until eventually a beautiful lustrous jewel, a pearl, is formed. We want to show that the abuse women go through can result in the formation of a pearl. The difficulties of life can form something beautiful and be a source of hope and inspiration to others.

View this post on Instagram

Sarbjit discusses what True Honour’s involvement has been with the Pearl Project Awards in Kingston-Upon-Thames, London, which is made up of diverse South Asian communities.

True Honour is part of the Kingston Women’s Hub setup by Voices of Hope. We offer support to all those suffering from abuse and need help. By offering to share our story we aim to give hope to other women from the community and be their support to speak up. We understand the cultural and the issues women face when they are trapped in situations they feel they cannot leave. We are here to help because we know what they are going through and they are not alone. We will listen and support them.

Alongside True Honour, there is certainly a growing amount of awareness of honour-based violence, particularly with organisations such as the Southall Black Sisters. Established in 1979, SBS has been pivotal in fighting for equality for black and ethnic minority women and challenging gender violence, providing resources and a safe space for vulnerable women. So why are there still so many South Asian women afraid to take the first step away from honour-based violence? Speaking from her own experience of having felt unsupported, Athwal says,

Women are afraid to speak up or come forward because they feel they will not be supported, no one will listen or understand them. Professionals and the police have a lack of understanding around cultural issues and understanding which they must learn before the right support can be given to any victim.

View this post on Instagram

Does Athwal feel that the so-called shame on the community and society that women are guilt-tripped into is the real issue even today despite the generational shift in how family units coexist?

There still really is so-called shame on the community especially from certain age groups. They were brought up in a way where they were suppressed and had to follow rules and didn’t really have a choice and believed their way of living to be a normal. This behaviour is now being passed onto the next generations and can sometimes it is hard to break the cycle.

Read more about the work carried out by True Honour here. Tickets to the Pearl Project Awards on 12 November can be found here.

Photo Courtesy of Sarbjit Athwal