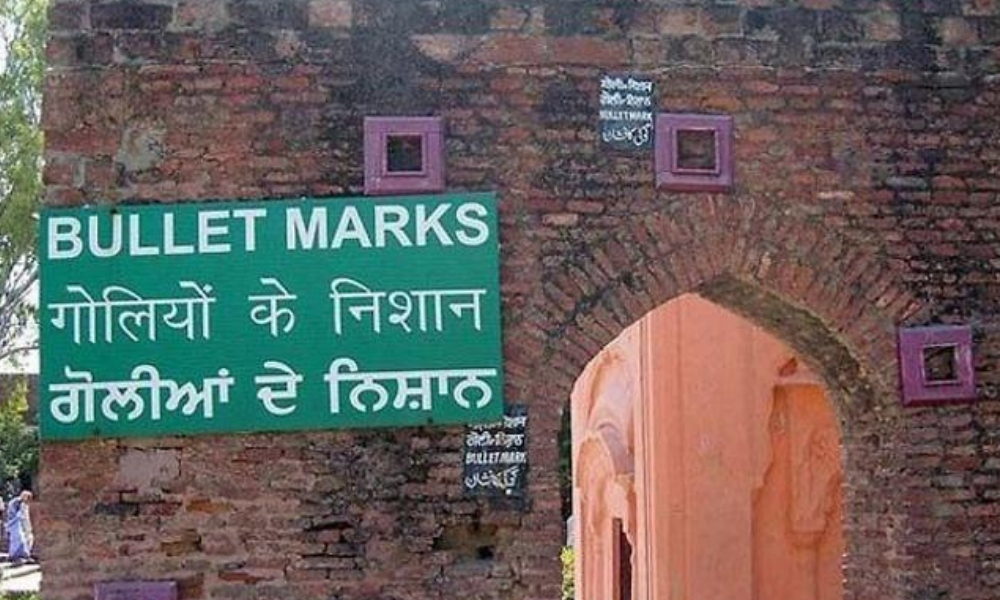

It has been 100 years since the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar, Punjab — when troops of the British Army under General Reginald Dyer’s command, fired shots at innocent bystanders at Jallianwala Bagh. The number of people whose lives were lost during those fateful 10 minutes — and later from wounds as the victims were denied medical treatment— is still unclear. It’s a sad and harrowing moment for South Asians worldwide, a reminder that such literal brutality and dehumanisation is only around four generations removed, only just beyond living memory.

South Asians possess a century-long relationship with Britain and those who came in the 1950s and ’60s onwards inverted the colonial hierarchies, placing decolonisation in the very heart of the ex-Empire. Britain’s lack of apology for the atrocities they committed on 13th April 1919 speaks volumes. Indians have made their mark in Britain, carved out their space and proved themselves to be a worthy and successful minority. We should be proud of this, but we can’t see this as meaning that our work is done.

[Read Related: British Royal ‘Splendours of the Subcontinent’ Collection Devalues India’s Fight for Independence]

Some may argue that we should stop living in the past, but Britain’s lack of apology signifies otherwise. Empire, massacres, violence, was not just something that was enacted out there far away from Britain’s shores. It is part of British history – our history. David Cameron issued a full apology in 2010 for the Bloody Sunday events in Ireland, the site of some of Britain’s other most shameful atrocities. An apology also needs to be accompanied by vast curriculum reform in schools and a change in the teaching methods of British history.

The Indians that live in Britain today built this country up again after the war, built the NHS, fuelled the factories and were at the heart of the genesis of modern Britain. Britain has always taken from South Asia what it needed. In the past, it was resources, and then it was people as they called for workers, even when India was no longer a colony. By colonising India, devaluing and distorting its own history, and telling its people they could, should and would be British, this country has to acknowledge that all that happened is as much part of Britain’s story as it is India’s.

[Read Related: How Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s Royal Wedding Represented Diversity in British Royalty]

The violence of empire is ingrained in the mindsets of the people, the streets of London, Manchester, Liverpool, and the ethnic makeup of the U.K.’s migrant communities. You only have to watch Satnam Sanghera’s Channel 4 documentary “Amritsar: The Massacre that Shook the World,” to see the mindsets that still persist in this country, still waiting to be confronted.

Many, including my own grandfather who went through so much at the hands of an insensitive, frivolous British decision to carve up the subcontinent, have asked what the point of an apology would be and what it would change. Many British leaders in the past including David Cameron and Theresa May have expressed “regret” and “sorrow” for the awful events — so what real difference would the addition of one word make?

Saying sorry cannot fix centuries of mistrust and unequal relationships — but it would restore respect. We are no longer the infantile inhabitants of an exotic land. We are here, on your doorstep telling you that after our ancestors were debased, humiliated, made to crawl down their own streets, therefore, one simple request deserves, indeed demands, to be heard, to give them their humanity and place in history back.

Satnam Sanghera’s documentary is still available for U.K. viewers, whilst the Partition Archive in Amritsar, with whom I have had the pleasure of volunteering with recently, are running exhibitions on Jallianwala Bagh in London, Birmingham, and Manchester for the rest of April. If you get a chance, I urge you to go and show solidarity.