by Priya Arora – Follow @ThePriyaArora

Faraz Arif Ansari still remembers the cold winter day in 2013 when India’s Supreme Court reinstated Section 377 of the penal code. He was working on the screenplay for his feature film, “Ravivar,” a mainstream semi socio-political satire with a homosexual protagonist.

“Suddenly, the image on the television in this quaint little café caught my eyes and I remember, as I got up from my chair, walking towards the television, I couldn’t feel my legs. I was numb. I was trembling, I was breaking down. I wanted to tweet, I want to write a Facebook post, I wanted to disappear. It was like the oxygen from our chests was pulled out and you were left bleeding on the walkway.”

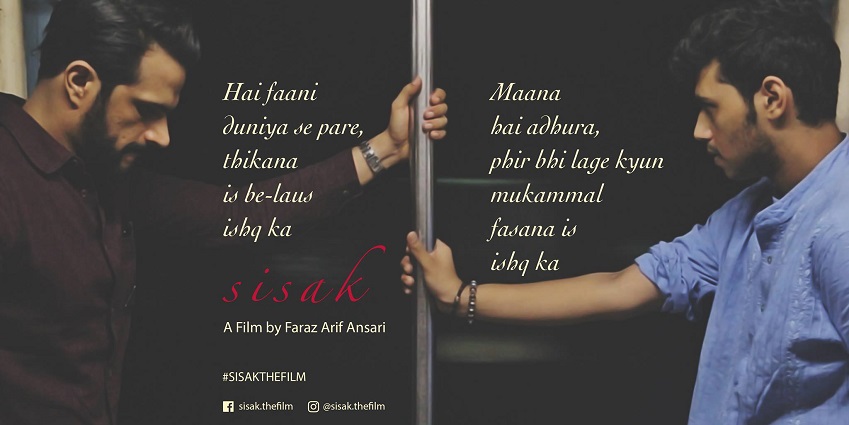

In one swift moment, Ansari faced the gruesome reality of being declared a criminal—and the moment inspired him to make (direct, write and produce) a new film with a powerful story that resonated beyond labels. Ansari has now made India’s first silent LGBT film, “Sisak.” The title An Urdu word mean

“Sisak” is a 20-minute silent film about two men who meet each other, over a period of many nights, on a Mumbai local train. Without a single word spoken, and without the possibility of physical intimacy, a strong, wordless romance blooms between the two. The title captures this aptly—sisak is an Urdu word describing a sob that is stuck in the throat.

Ansari knew when the film was born, he said, that it had to be a silent film.

“Silence is the most piercing sound,” Ansari said. “Other than being a political statement about the state of the LGBTQI community in India, there exists a state of immense need to be heard by the community,” Ansari explained. “As a filmmaker and a storyteller, I feel we use too many words to convey what we feel. People need to feel what you are feeling and when there are no words to support the visuals, [this happens] by default.”

The power and intimacy of transporting the audience into the minds of the character, Ansari said, is the kind of roar the community needs. Despite examples of solidarity such as Pride marches, almost every LGBTQI film is about people’s struggles with their families, with themselves, about coming out, etc. But at its essence, the story is not seen as between two men as men but instead as two individuals who are yearning to love and to be together—but because of society, and law, they are unable to.

“We want people to know that ‘Hey, we are just like you!’ and I feel that with ‘Sisak,’ that has somewhere been achieved. We are all the same. What binds us all together is our similarities, our likings and that is how we understand each other. Once that barrier of difference is broken, we shall flourish.”

The story of “Sisak,” is indeed universal. The intrigue, excitement, and power of unspoken romance are alluring and relatable. It is a film for anyone who has ever loved, or been loved, or never had the courage to walk up to someone and express how they feel. As Ansari put it, the characters’ own simplicity is what makes their complications and vulnerabilities all the more powerful.

“There’s no running around the tree, no Swiss Alps, no Dolce & Gabbana clothing, heck, not even a camera track! Just two lost souls, on their way back home, when they discover a home in each other.”

According to Ansari, ‘Sisak’ is a return to the unspoken, unsaid and universal expressions of love, on the path of subtlety and humanity.

“‘Sisak’ is the result of the belief that if love knows no bounds, it need not be bound by words, either.”

And “Sisak” has indeed found success, albeit after its own challenges. Ansari, having already worked as a writer and producer in the film industry for 8 years, including 2011’s “Stanley Ka Dabba,” faced challenges in finding funding for “Sisak.” He put half his life savings into making the film and combined with a successful crowdfunding campaign, completed post-production.

“I remember sitting in front of my bank statements and thinking, if I could truly invest more than half of my life’s savings into making this film happen. They told me “It’s a gay film, no will watch it!” – and then, I remembered all the times that I have been laughed on, heard homophobic slurs thrown on me, sometimes, been abused emotionally and physically for being who I am. It was like a quick montage of imagery and emotions that flashed in front of me and then, I knew it, that I have to make ‘Sisak.’”

Ansari remembers this moment, the decision to make this film, as his best memory of the production. And despite its challenges, that of production and silent filmmaking and low budgets, the film is here and creating a roar, as intended. The response to the film has been overwhelming, Ansari said.

“On a regular day, I get about 30 messages on Facebook from individuals who are in the closet and now want to come out after watching the trailer. It makes me think how powerful 2 minutes of honest & truthful cinema can be.”

[Read Related: “‘An Unsuitable Boy’: On Karan Johar and Coming Out“]

“Sisak” also received an endorsement from Sonam Kapoor earlier this year—she launched the film’s trailer—which has been a big step in catapulting the film into the consciousness of audiences around the world. Ansari said they call Kapoor “Sisak’s” fairy godmother.

“Sonam Kapoor has been extremely wonderful for coming forward and supporting Sisak,” Ansari said. “When you are such a huge influencer and have such powers to inspire so much young minds and you use your powers wisely in actually giving sunshine and attention to what is the dire need… it speaks volumes of Sonam as a human.”

And, of course, not all responses have been so positive. Ansari said that he has received countless hate comments and emails filled with threats. He recalled once being approached by a man at an airport shortly after a group of fans had taken a self with Ansari. Asking him if he was the “gay guy who made the gay love film,” the man called Ansari a derogatory name and spat on his sandwich.

But, Ansari said he doesn’t let the hate get to him. He said he feels an immense amount of love and support, especially because of the important message his film carries.

“I am just glad that people are talking about Sisak and indirectly about the LGBTQIA+ community. I was attending the National LGBTQ Conclave at IIM Kozhikode, India’s Premiere Leading Business School and the first question I was asked was “What is LGBTQ?” You see, that’s the problem. Most people are fearful because they are unaware. What they don’t realize is that we are their children, their siblings & their friends. When they see that, the differences will fade away—but for that to happen, a dialogue has to be opened and Sisak is doing just that.”

Ansari is now taking the film on a worldwide tour, featuring at film festivals in the U.S., Greece, Mexico, France, and much more. He is also in talks to find distribution as well as create a crowdfunding campaign to travel around India with free public screenings n both rural and urban areas.

Ansari also divulged to Brown Girl Magazine that beyond the scope of a 20-minute silent film, Sisak has inspired him to make a silent feature film based on the film.

“It will be called ‘Sifar’, an Urdu word, which means ‘Void’. In this film, I want to explore the backstory of Dhruv’s character (the boy in the Kurta) and Jitin’s story from where we begin Sisak and beyond. Maybe we will never see them together again. Maybe we do. But the film is going to be about the piercing loneliness in the life of a homosexual and the everyday battles that one has to fight, be it inside the closet or outside. For us, every day is a coming out day. Imagine a life like that where acceptance doesn’t exist and love is crime and so it should be forgotten. It will be about that yearning for that fleeting sense of belonging that all of us crave for. After all, aren’t we all lonely, always? Millions of people, looking for others to fulfill them, and yet isolating themselves.”

At its core, “Sisak” is a universal film about love. But “Sisak” is not just that—it is also a strong social and political statement about a part of the population that has been denied the right to love openly and honestly—and so it is silent. Sisak is also about a redundant, inhumane law that isn’t against love. Some also call it an allegory to Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. And truly, that’s how cinema should be – everything, and at once.

Upcoming screenings of “Sisak” include Harrisburg, Penn. on April 16. and the New York Indian Film Festival in NYC on May 2. You can catch “Sisak” at a film festival near you—check out the film’s official Facebook page for more information.

Priya Arora is a queer-identified community activist, editor, writer and Netflix enthusiast. Born and raised in California, Priya has found a home in New York City, where she currently works as a Web Editor at Hearst Business Media. When she’s not working, Priya enjoys watching old school Bollywood movies, performing at open mics, laboring over NYTimes crosswords, reading books she never finishes, and eating way too much of her partner’s homemade Hyderabadi biryani.

Priya Arora is a queer-identified community activist, editor, writer and Netflix enthusiast. Born and raised in California, Priya has found a home in New York City, where she currently works as a Web Editor at Hearst Business Media. When she’s not working, Priya enjoys watching old school Bollywood movies, performing at open mics, laboring over NYTimes crosswords, reading books she never finishes, and eating way too much of her partner’s homemade Hyderabadi biryani.