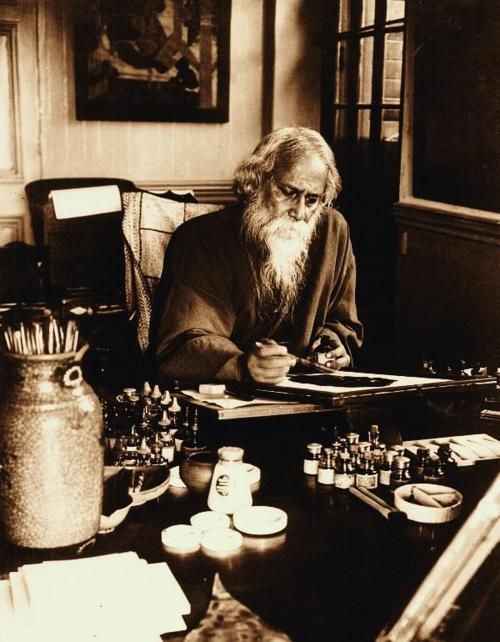

Rabindranath Tagore is one of the most prominent cultural icons of pre-partition Bengal and, arguably, India at large. He was a late nineteenth/early twentieth-century creative genius who penned scores of plays, short stories, novels and poems, as well as thousands of short songs, including the national songs for India (Jana Gana Mana) and Bangladesh (Aamaar Sonar Bangla). He was the first non-European to win a Nobel Prize in Literature and is one of the most celebrated proponents of the Bengal Renaissance. Tagore’s works have made their way into dozens of Bengali and Hindi film adaptations. Nothing, however, is quite as pure and honest as Anurag Basu’s “Stories by Rabindranath Tagore.”

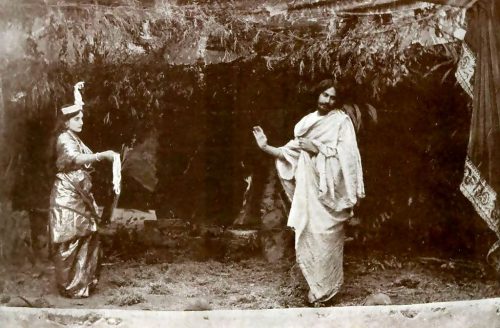

The series is divided into 26 episodes of some of his most famous stories, intermittently accented by his own musical compositions. Just a few episodes in, it becomes very clear why Tagore’s works have not been more widely adapted and produced beyond his beloved Bengal—the Indian Censor Board would surely never allow the controversial themes captured in his works to find new life on screen.

Specifically, he was highly critical of the Swadeshi movement that was prominent in Bengal in the early years leading up to independence—a movement that focused on national self-sufficiency, advocated for the boycott of all foreign goods, and became known for its violent protests. Tagore was horrified by the violent effects of Swadeshi demonstrations and rejected the economic resistance effort because of its ruinous consequences for Muslim traders throughout the country. Instead, Tagore’s brand of nationalism advocated for independence gained through education and reconciliation between the western and eastern worlds, rather than through blind revolutionary impulses and the rejection of all things British.

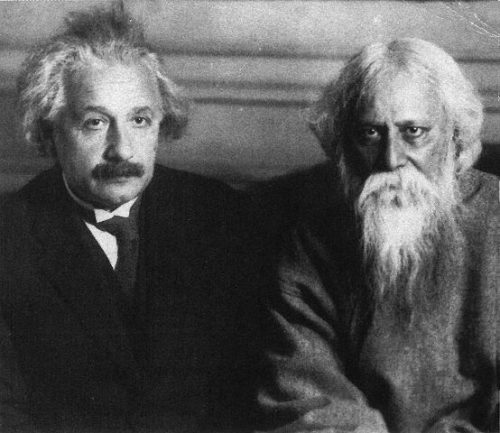

Notably, the feeling was mutual, as many of his countrymen (even today!) considered Tagore to be an anti-nationalist. Despite the popularity of his work, Tagore’s privileged upbringing among the Bengali elite, in addition to his contrary political stances, created friction among his readership. While prevailing nationalist movements centered their pride on remaining within India and rejecting foreign contact, throughout his life, Tagore traveled to over thirty countries, meeting dozens of dignitaries and intellectual icons in the process. Again, to refocus on the significance of his privilege, he simply was not an accessible writer for those who could not comprehend or connect with his lifestyle and largely counter-cultural convictions.

In its simplicity resides a beauty that will bring you closer to the genius of Tagore and his romantic sensitivities, as well as to his staunch political sensibilities and apparent disillusion with the societal status quo. Each episode is a testament to the brilliance of a literary canon that is worthy of veneration next to Tolstoy and Frost, yet somehow stifled and underrepresented. His characters are honeycombs of flying emotions leading lives filled with captivating commotion. They will stay with you long after you have finished watching.

Elizabeth Jaikaran is a freelance writer based in New York. She graduated from The City College of New York with her B.A. in 2012, and from New York University School of Law in 2016. She is interested in theories of gender politics and enjoys exploring the intersection of international law and social consciousness. When she’s not writing, she enjoys celebrating all of life’s small joys with her friends and binge watching juicy serial dramas with her husband. Her first book, “Trauma” will be published by Shanti Arts in 2017.

Elizabeth Jaikaran is a freelance writer based in New York. She graduated from The City College of New York with her B.A. in 2012, and from New York University School of Law in 2016. She is interested in theories of gender politics and enjoys exploring the intersection of international law and social consciousness. When she’s not writing, she enjoys celebrating all of life’s small joys with her friends and binge watching juicy serial dramas with her husband. Her first book, “Trauma” will be published by Shanti Arts in 2017.