by Salwa Tareen

Late one night in December, Suraiya Ali, or @iranikanjari, tweeted a photo of her torso and brown boys everywhere lost their minds.

Although Suraiya, an 18-year-old student of Irani, Indian, and Pakistani heritage from Texas, had already gained a loyal following on Twitter, she said—in an exclusive interview with Brown Girl Magazine—she did not expect this kind of attention:

“This has been the biggest shock of my life. And at the beginning of 2016? This year will be crazy.”

Instead of ignoring the trolls, Suraiya chose to fight back and have a laugh along the way:

“…these boys are IDIOTS. I’m smart. I’m not going to sit here and say I don’t have a knack for rhetoric. Being bullied and being smart in real life—it’s hard to clap back since the bullies will physically shut you up. But on Twitter? Man, they can’t do anything. And I can say whatever I want back. This is my platform. And I’m going to use it.

Half these boys think I’ll ignore them, but if I can exploit their ignorance to reach more women and make them laugh while helping them love themselves—why wouldn’t I? Being carefree, to me, means I will take your insults and make them work for me. I’m not here to be docile, you come into my mentions and I will notice you. Brown men especially. We come from the same place, I’m not letting anything you do slide. If your mother won’t hold you accountable— I will.”

[Read Related: One Brown Girl’s Perspective on What it Means to be Carefree]

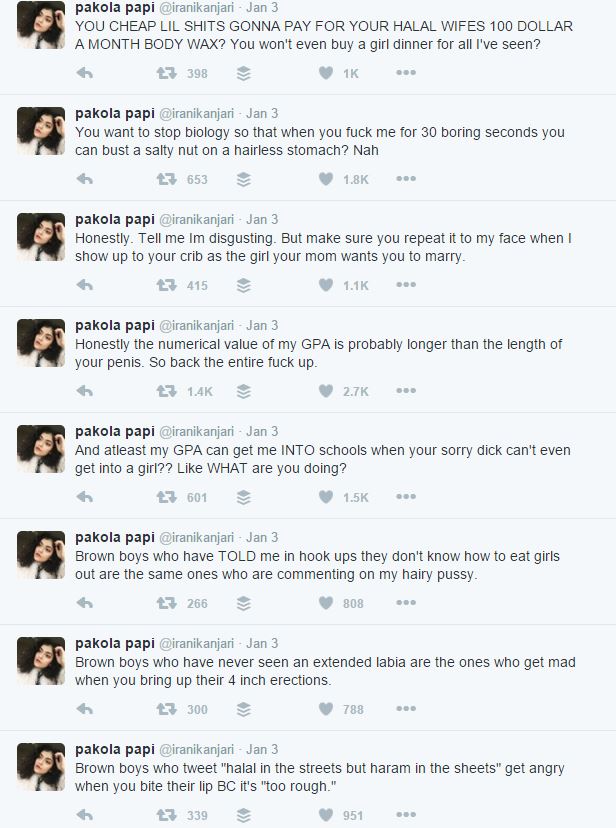

What followed was a glorious 23 Tweet-long clap back putting brown men on blast for criticizing the natural beauty of brown women, to uphold sexist double standards.

According to Suraiya, the reasons brown men are threatened by the idea of brown women accepting themselves are rooted in a history of inequality:

“Well, if they can’t subjugate us, what use are they? I mean, honestly, I can’t think of anything more powerful than a woman of color. And I think men know this. Now, that’s the poetic answer. Men have upheld power since the dawn of whatever creation you believe in, and homeostasis isn’t something the powerful like to see disrupted.

You can boil it down to power, to money, to greed, to religion —whatever. They don’t want to see us as equals because then they’re forced to face every atrocity they ever committed against us. We talk about white guilt, but male guilt? Rarely said. ‘I’m a nice guy’ = male guilt. They don’t want to see us win because then they have to admit they played dirty.”

As for her self-care routine and how other brown girls can deal with haters both on and offline, she has a few practical tips:

“[I] recently became a fan of Lush shower jellies and Vatika hair care products. Also, ask your mom for the remedies she did back home, those never fail to work. Dealing with haters: know how to cuss them out in your mother tongue. If that’s not an option, be as humorous as possible. When you’re funny, they panic.”

Now that the excitement of the first photo and subsequent rant has died down, Suraiya hopes people following online realize she’s only human:

“I’m a giant nerd who is constantly spilling things. I’m so human. Like I want them to know I’m beyond human. I mess up so much. And I’m only here to learn more to help everyone be an amazing version of themselves.”

We love how awesome-ly human you are, Suraiya! Continue empowering woman to love their bodies! <3

Check out some of the love she received from women around the world:

Brown girls, stay tuned for Suraiya’s blog post next week!! (We can’t contain the excitement!)

[All images are screenshots via Twitter.]

Salwa Tareen is a recent college graduate, community organizer, and writer from Kalamazoo, Michigan. Through her work, she seeks to explore the intersections of language, identity, and politics whether it’s in the form of a poem, dialogue, essay or literature review. In her spare time, as a Pakistani-American woman born in Saudi Arabia and raised in Canada, Salwa enjoys crafting clever quips to the question: “No, where are you really from?”

Salwa Tareen is a recent college graduate, community organizer, and writer from Kalamazoo, Michigan. Through her work, she seeks to explore the intersections of language, identity, and politics whether it’s in the form of a poem, dialogue, essay or literature review. In her spare time, as a Pakistani-American woman born in Saudi Arabia and raised in Canada, Salwa enjoys crafting clever quips to the question: “No, where are you really from?”