It’s 1879 Calcutta, India.

The smell of sea salt rises as workers melt into crowded lines. A large ship towers overhead, churning along teal waves of the Indian ocean. You wait by the depot with fear and hope mixed in your eyes, envisioning a better life. It’s only 5 years, you tell yourself. Only an island 700 miles away.

Except 5 years turned into generations and 700 miles became 7,000.

On May 14, 1879, the Leonadis sailed through the warm waves of the Southern Pacific, marking the era of indentureship in Fiji. After the “abolishment,” of slavery, the British indentureship system reinvented slavery for cheaper labor. Indentureship first began in Mauritius with 39 laborers and continued throughout the West Indies and South Africa. While it ended in 1917, the lasting effects are still felt today. Over 60,000 Indian indentured laborers left their homes to never return. Some originated from areas of Calcutta and Madras, some stolen and manipulated into deceitful contracts. They were bound to this land and agreement for as long as 5-10 years.

[Read Related: Book Review: Two Times Removed: An Anthology of Indo-Caribbean Fiction]

Indentured servitude thus became a saturated attempt to reintroduce slavery in a new legal form. The workers referred to this labor as Girmit, which stemmed from their pronunciation of the English word agreement. This word was born from workers who did not speak or read English, struggling to understand the exploitative agreement they were involved in. Girmitya or Girmityas refers to the workers who carried out the Girmit (work).

With the resettlement of over 1.3 million indentured workers across British colonies, the culture and population of Indo Fijians grew significantly. Growing up as Indo Caribbean woman, I learned later on about the painful origins of my culture. I discovered that a greater community existed in the aftermath of indentureship, one that collectively shared histories and traumas of colonialism. Whether through manipulation or will, they were brought to different pockets of the world, becoming a diaspora of indentured laborers.

Female Girmityas

The ratio of male to female workers showed fewer women with 13,696 out of 64,480 laborers. Female workers were treated as inferior by their male workers and sardars (overseers). The notable story of Kunti, a worker from the Lakhuapur village in Gorakhpur, has survived despite a long history of facing cultural erasure. The story of Kunti is well known among Fijians as her experience amplified awareness of the horrors of indentureship. After escaping sexual assault by her overseer and jumping in a river, Kunti was rescued. Her story was published in the Bharat Mitra and publicized in India, encouraging the government to inquire about the treatment of Indian indentured women.

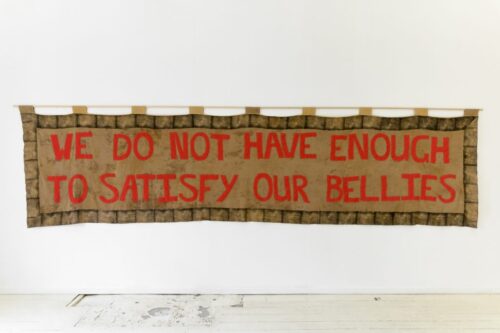

In 1920, after the abolishment of the indentured system, female workers led a rebellion in Suva to protest the lack of food provided for workers. The collective, Bad Fiji Gyals, a movement created by Quishile Charan and Esha Pillay pays close attention to the patriarchal narrative that dominates this retelling of history and minimization of women’s roles.

In “Undoing History’s Spell on Bad Women,” Pillay says “As we examine the 1920 strike, we find it impossible and unconscionable to ignore how female Girmitiyas resisted in different ways against many colonisations and patriarchies. The way female Girmitiyas have been historically underestimated and violently silenced is why we are so infuriated.”

The preservation of history through the lens of male narratives has hidden and invalidated the experiences of Fijian women. Bad Fiji Gyals has served as an educational platform to dismantle these Western accounts of history while attempting to accurately represent stories of indenture.

No Ties 1879: A Podcast for Indo Fijians

“I’m not Brown enough to be brown because we’re not directly from India, not Fijian enough to be Fijian because we grew up in Ladner.” – No Ties 1879 –

Sibling duo Angelene and Ashneil Prakash discuss Indo Fijian representation and pressing social justice issues in their podcast, No Ties 1879. “No Ties 1879 was born out of an assessed need by us to properly address every question that we have personally, and that we have received. To the best of our intention and ability, we strive to raise and amplify the profile of the Indo Fijian identity and expose the system that created it.”

The podcast exposes the reality of being Indo Fijian and the struggle to find a sense of belonging. Growing up as Indo Caribbean, I recall finding videos on Youtube of familiar music composed by Indo Fijians. I realized these musical traditions mirrored that of Indo Guyanese and shared similarities despite being oceans away.

View this post on Instagram

Navigating Identity

“We exist in a place and space that our upbringing consistently told us we shouldn’t,” says Angelene Prakash.

Through multiple migrations, descendants of indentureship had left the colony they were taken to. As a group of people whose value was reduced to the labor they produced, migration fueled this concept again.

Many of these populations have grown in Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States, the Netherlands and New Zealand. These siblings discuss their experiences growing up in Canada.

“We grew up in a very small predominantly Caucasian suburb of Greater Vancouver. We always corrected people when they referred to us as Black. We would then usually get asked, “Well then why is your skin so dark?” There was a very narrow understanding of culture in our town that existed in the binary of ‘white’ or ‘Black.’ This put us in a position to have to explain ourselves to white people. Amongst brown people, we needed to legitimize ourselves.”

Many Indo Fijians and descendants of indentureship face incidents of marginalization from other South Asian spaces. Our identities are consistently called into question and held to standards of South Asian culture. This invalidates our experiences and those of our ancestors.

“Being questioned on the validity of our heritage, culture, or ancestry is infuriating. In real life, it manifests as folx from other brown cultures judging the way we speak our dialect of Hindi: Fiji Baat. We’ve been told by brown folx that we’re not really Fijian because we’re not indigenous to the archipelago. They also say that our culture is watered down, therefore, is not authentic.”

The history of colonialism has allowed for the emergence of cultural groups that live within this paradox of identity. Neither Indian nor Fijian, neither English nor ‘Hindi,’ What results from a culture denied in its existence? Not ‘good enough’ to claim roots or a home?

Indentured worker, displaced migrant, Girmitya or Coolie — these words hold a connection to colonialism that has defined diasporas of South Asians. The struggle to feel represented in a world that doesn’t see you is both an isolating and challenging dilemma. Storytelling has become a powerful tool to preserve culture and facilitate conversations around indentureship.

For the sake of survival, our ancestors had to adapt to conditions that meant sacrificing their autonomy. The result was a culture of resistance that withstood the cruelty of colonialism.

[Featured Image Credit: Shutterstock]