“Ms. Ravindrababu, I don’t get it.”

“Oh, yeah, we did that in Ravindrababu’s class.”

“Do you have a pencil, Ms. Ravindrababu?”

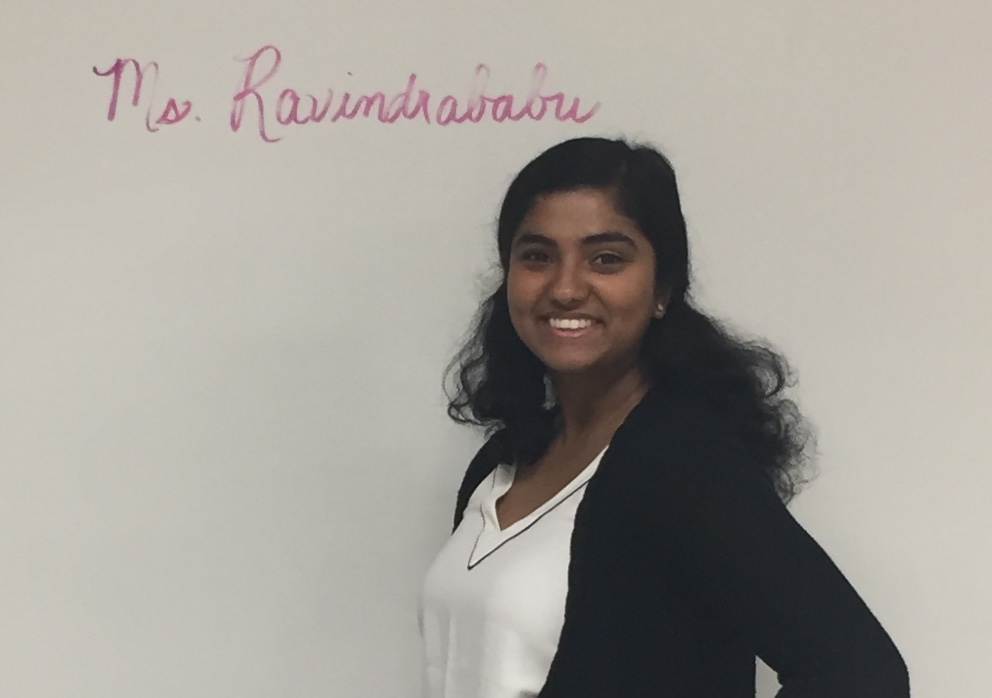

Ms. Ravindrababu

I smile every time a student calls to get my attention.

I became a teacher in August of 2018. I had no idea what my students would call me. I knew I had a “difficult” name. A name that was too long. A name that was too different. In addition to being brand new to the classroom, I was also brand new to my community.

I had relocated to the Eastern Kentucky region of Appalachia to become a teacher through the Teach for America program. The community I am now teaching in is vastly different than the one I grew up in just outside of Boston. My new community is 98 percent white. Only 10 percent of adults have a college degree. The primary industry here had been coal, but no longer. A full two-thirds of the population lives below the poverty line. Moving here, as a woman of color, as someone different, I anticipated that I may have a hard time fitting in. I didn’t want to make it any harder.

Until the week before school, I hadn’t even considered the thought of teaching the children how to say my name. I was toying with different abbreviated options during a professional development session when a colleague asked me the question I had been subconsciously dodging all along. “Why don’t you want them to say your full name?”

[Read Related: Say My Name, Say My Name (Or At Least Try, Dammit)]

I didn’t know what to say. I stuttered out something about it being too difficult, not wanting to go through the trouble. He advised that I try it and that I shouldn’t underestimate the students. Feeling respected in your classroom was definitely worth the trouble. He suggested that saying my name could be the first “lesson” I taught my students before diving into all the math content. Feeling suddenly empowered by this validation, I agreed. I wasn’t in Boston anymore. This would be the first time many of my students had ever encountered an Indian American in their lives, and definitely the first time they’d heard of a name like mine.

With my newfound confidence and sense of self-validation. I approached the first day of classes. I told the students about the syllabus, classroom procedures, and a little bit about myself. Then came the activity I’d planned to teach them my name. I broke it down syllable by syllable and had them repeat after me, stringing it together into more complete chunks as we went. Finally, I had them practice in pairs, seeing how many times they could say it in 15 seconds. The pair with the highest tally won bragging rights.

No one complained. No one made fun of me. There was the occasional query: “What if I just called you Babu?” or “How about Ms. Ravindra?” but nothing further by way of protest. And by the end of the first week, everyone pretty much knew how to say it. That was it. That was the first lesson I taught my students. The check for understanding that followed revealed nearly 100 percent mastery of the skill. All 110 of my students from Floyd County, Kentucky had learned how to say my name. They had managed a task that had eluded all of the educated, well-off folks back home, all of the teachers from my own high school. They’d bested my assistant principal who hadn’t managed so much on my graduation day. They bested the MCs at every event I was ever called on stage for.

[Read Related: Decolonizing the Minds of Indians Starts with Our Names]

After all of the years of incorrect pronunciation, I’d given up on the idea that others would say my name correctly. More importantly, I’d given up on respecting myself enough to insist that others get it right. In August of 2018, a classroom of 110 students gave all of that back to me. This experience has been an important lesson for me: The point is not that people are able to say my correctly name the first or even the 10th time they say it. The point is that I respect myself enough to insist that they will get it sometime anyway. The point is that I hold people to higher standards. The point is that now anytime someone says off-handedly “Oh, I’m never going to get that right,” I can playfully jab back “Well, if 110 high schoolers can manage it, I’m sure you can, too.” The point is that in a school building, in a part of America that many have written off as being too “redneck” or “ignorant,” with a name that’s been written off as too “difficult” or “different,” me and a group of kids got together and proved the whole world wrong.