by Shefali Chandan – Follow @janohistory

Indians and African Americans share social and political connections that go back to the late 19th century. These connections, grounded in the shared anti-colonial and anti-racist histories of the two groups, and their impact on American politics and culture, are usually overlooked in historical accounts of Indo-US ties.

In addition to the well-known influence of Mahatma Gandhi on Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the American civil rights movement, there have been many other influential Indo-African American links–from W.E.B. Du Bois and Lala Lajpat Rai to Paul Robeson and Bhupen Hazarika; from Howard Thurman and Gandhi to Oprah Winfrey and Aishwarya Rai Bachchan.

African Americans feel a sense of solidarity with continental Africans, but it was during World War II that this solidarity was extended to all people of color. Black newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier, The Crisis and the Chicago Defender played a key role in informing African Americans about the struggles of colonized countries in Africa and Asia. These accounts, by writers such as Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, Paul Robeson and William Scott, linked the anti-colonial struggles in Ethiopia, Nigeria and India with the anti-racist struggles of blacks in America. Thus, these writers demonstrated the universalism of their goals and gained greater leverage in their own struggle for civil rights.

[Read More: Addressing South Asian Anti-Blackness: The Attacks on Africans in India]

One of the greatest proponents of solidarity between people of color was W.E.B. DuBois (1868-1963), an African American civil rights activist, writer, historian and professor. He was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909 and also served as the editor of the NAACP’s main journal, The Crisis. Upon India’s independence in 1947, he is quoted by authors Bill Mullen and Cathryn Watson in their 2005 book, “WEB Du Bois on Asia: Crossing the World Color Line” to have said:

“The fifteenth of August deserves to be remembered as the greatest historical date of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This is saying a great deal, when we remember that in the nineteenth century, Napoleon was overthrown, democracy established in England, Negro slaves emancipated in the United States, the German Empire founded, the partition of Africa determined upon, the Russian Revolution carried through, and two world wars fought. Nevertheless, it is true that the fifteenth of August marks an event of even greater significance than any of these; for on that date four hundred million colored folk of Asia were loosed …”

Du Bois also befriended Indian nationalist Lala Lajpat Rai during the latter’s five-year stay in the U.S. during World War I. They became close, collaborating on issues related to Indian Independence as well as American civil rights. Du Bois gave Lajpat Rai an introductory letter which enabled him to meet with Booker T. Washington and tour Tuskegee University in Alabama. Even upon his return to India, Lala Lajpat Rai remained Du Bois’ main contact and source for matters related to India. Du Bois wrote frequently about him in The Crisis, viewing Rai as his main source for Indian events and news. Many years later, even after Rai’s death, Du Bois said of him,

“Lajpat Rai understood and wrote about the Negro problem in America.”

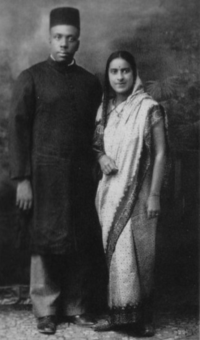

The very first African Americans to meet Gandhi were the Thurman – Howard and his wife Sue Bailey. They were key members of an African American delegation to India, Sri Lanka and Myanmar in 1935-36 called the “Pilgrimage of Friendship.” The delegation was organized by the Student Christian Movement of India. Accompanying them on that trip were Mr. and Mrs. Edward G. Carroll. It was upon meeting Thurman that Gandhi famously remarked,

“It may be through African-Americans that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world.”

Courtesy: Public Domain]

Other African-American luminaries who came to India include Mordecai Johnson who became the President of Howard University and Bayard Rustin, the famous leader of social movements in civil rights, gay rights and pacifism.

In his book, “Raising Up a Prophet: The African American Encounter with Gandhi,” author Sudershan Kapur remarked, “Long before the rise of Martin Luther King Jr., a growing number of African Americans not only grasped the relevance of the doctrine of non-violence to their own situation in this country, but also sought to experiment with its uses. Thus, the soil which had been prepared and nurtured for a generation and more by some of the key African-Americans was ready not only to receive the seed of non-violence but also to bear fruit as never before”.

In the excerpt below, taken from his essay. “What we may learn from India,” Thurman describes his meeting with Gandhi:

We arrived at the nearest railway station to Bardoli at three o’clock in the morning and were met by Mr. Gandhi’s secretary. He took us to a bungalow tent in a large mango grove to rest until daylight. While the other members of our party slept, the secretary and I talked about many things until it was time for breakfast. After breakfast, we left for our rendezvous in a model T Ford. In a matter of two or three hours we came to a large clearing, somewhat like an open field, in which there was pitched a tent before which was a flag pole flying the banner of the Indian National Congress. As the car approached, Mr. Gandhi himself came through the door of the tent to give us a personal greeting. We were escorted into the tent and seated ourselves on the floor and our conversation began.

(….) More than three-fourths of the time was taken by Mr. Gandhi asking many, many questions about Negro life in America, about human slavery and about the mental and spiritual state of the American Negro. He wanted to know about illiteracy in the various sections of the country, about how the laws operated in terms of civil rights, about education, the extent to which schools were separate and of what calibre they were. He was concerned about employment and living conditions, about the various forms of violence to which we were subjected. He was quite curious to what extent the American Negro had any communication with the native peoples of the great continent of Africa, how sympathetic we were to them in their struggle and to what extent did their students come to America to study and how they were treated.

One such influence has been jazz which, of course, has its origins in African American communities. Starting in the 1930s, Bollywood dance numbers were replete with jazz influences brought to India by African American musicians like Leon Abbey, Teddy Weatherford and William “Crickett” Smith.

[Read More: The Travel Ban Isn’t New: America’s History of Restrictive Immigrant Legislation – Part I]

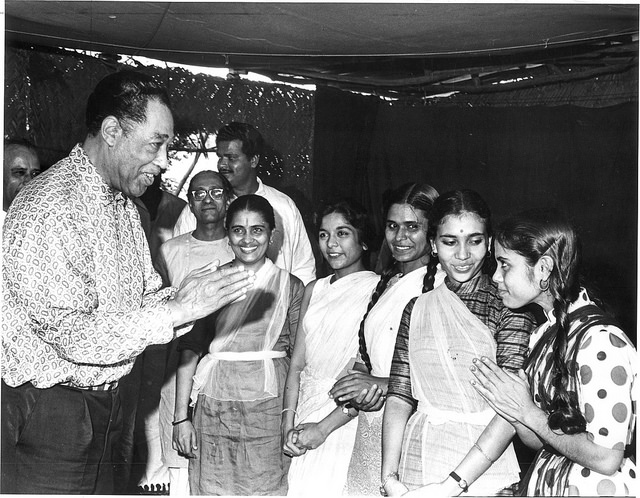

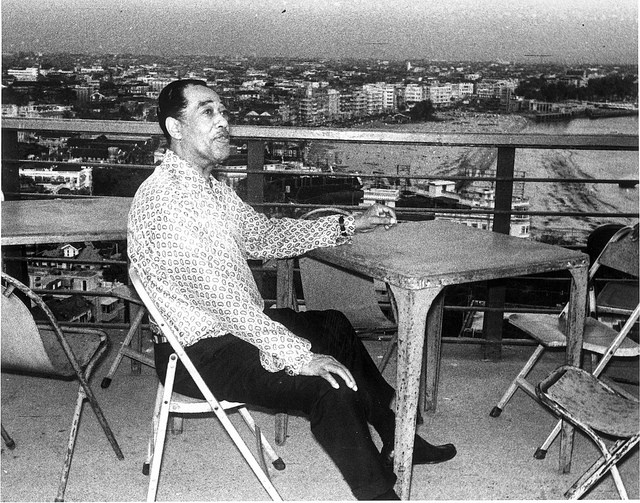

These influences were further integrated into Hindi cinema by Goan Indian musicians such as Frank Fernand, Anthony Gonsalves, Chic Chocolate and Sebastian D’Souza. In 1963, Duke Ellington, traveled to several countries, including India, as a cultural ambassador for the State Department. He toured many Indian cities and his popular album the “Far East Suite” was inspired by his travels there.

There remain many cultural exchanges between Indians and African Americans. Among the many African Americans who sojourn to India regularly are Jesse Jackson, Martin Luther King Jr’s children, Alice Coltrane (musician wife of saxophonist John Coltrane and founder of a Vedantic Center in California), Oprah Winfrey, Spike Lee and Tina Turner. Through this continued outreach, African Americans continue to pursue their dream of a global community of color.

Shefali Chandan is an educator and editor of Jano, the online history magazine for Asian-Indian families. She has worked for two decades in children’s media at organizations like Scholastic, Time Inc. and PBS Kids. Shefali has always been a history buff and now brings her extensive experience in education to craft high-quality content taken from stories in history for South Asians in America and elsewhere. Shefali lives in Reston, Virginia with her husband and daughter. She may be reached at editor.jano@gmail.com.

Shefali Chandan is an educator and editor of Jano, the online history magazine for Asian-Indian families. She has worked for two decades in children’s media at organizations like Scholastic, Time Inc. and PBS Kids. Shefali has always been a history buff and now brings her extensive experience in education to craft high-quality content taken from stories in history for South Asians in America and elsewhere. Shefali lives in Reston, Virginia with her husband and daughter. She may be reached at editor.jano@gmail.com.