by Richa Das – Follow @dasricha44

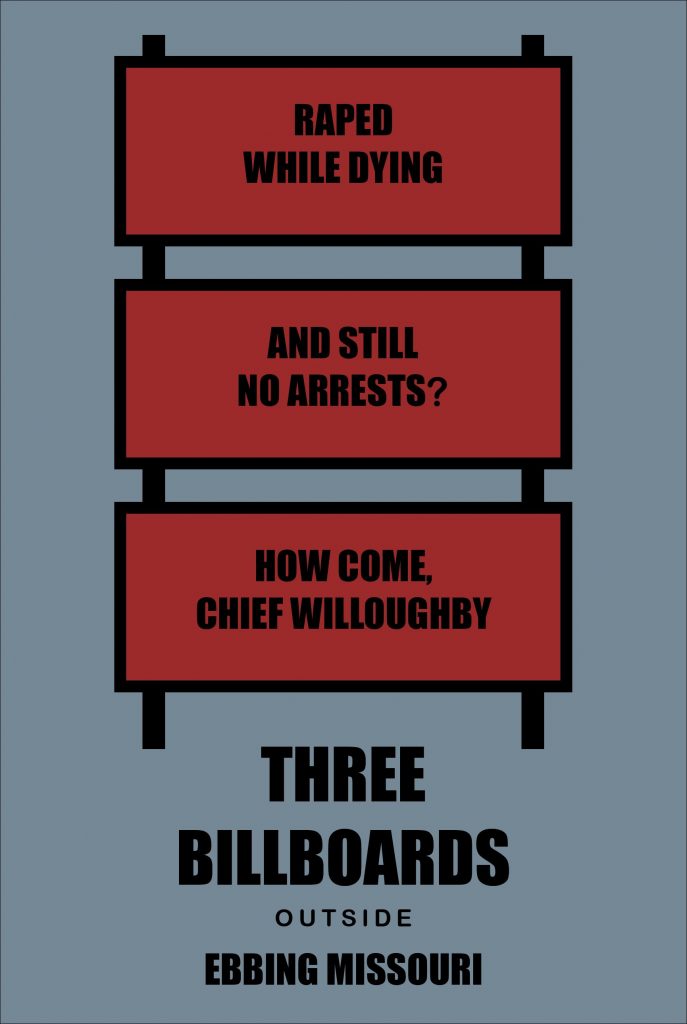

I would like to indulge in the good kind of cliché, one with which I join the herd that can’t stop praising the creators of “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri.” As someone preoccupied with context and an urge to constantly find meaning beyond the obvious, the film is an intellectual treat. It becomes clear in the very first few moments of the story that this isn’t going to be about conventional womanhood and treating issues that have become the norm in our world. It’s going to be about a “b*tch,” one that barks loud, clear and persistently.

As someone who has been an audience to several understudied and over-consumed revenge-dramas in India, “Three Billboard”’s take on the subject of violence against women is overwhelming. A clearly drawn narrative of the rape and murder of Mildred Hayes’s daughter in comparison to her own history with domestic violence becomes the very pivot around which I see the entire movie. The plot offers several distractions—from discussions of race to men that were bad and yet not that bad—everything is bound by Mildred’s tenacity, her questioning gaze over morality, legality, and femininity. It was essential for me, as a young woman traversing the contemporary film world, to look at characters that barged right through these boundaries in their discussions of the trauma of rape, violence, legal “blindsidedness” and the unnerving need to punish the culpable.

The hysteria surrounding the rape, for once, isn’t saddening. Maybe Mildred owes this to the black comedy genre that she is written in, but she never saddens me. She cries when you would have already expected her to and laughs not till the end and yet when she does, it is not lovely or resonating, it simply reminds you that she laughs because she has been denied every other aspect of her sanity. It frightens me how much I could relate to her will to get every man in Ebbing to testify, to prove his innocence.

Amidst racist and sexist characters, the story finds the space for subversion in more intimate, domestic spaces. Mildred, though separated from her demonic husband, is still shadowed by him and a fear of what he might be doing to other women in his life. Through the course of the narrative, even when Mildred spirals, she embodies the temperament and astuteness of a man. Her necessity to hunt down the perpetrators becomes her final cry, her final act within the parenthesis of revenge.

“Three Billboards,” though set in a different political American climate than the present, caters to very relevant policies of today, questioning authority and institutions. Thank you, Frances McDormand, for building one of the sharpest, smokiest female characters I have ever seen. She moves, talks and threatens exactly enough to tell you that she is crazy and not becoming crazy, that she will have the blood of all that have wronged her—stirred but never shaken.

Writing makes Richa Das jubilant and reminds her that mere existence is a cause big enough to celebrate, especially in a country like India, where there is no passing moment in which you aren’t contributing to something beyond yourself.

Writing makes Richa Das jubilant and reminds her that mere existence is a cause big enough to celebrate, especially in a country like India, where there is no passing moment in which you aren’t contributing to something beyond yourself.