by Shefali Chandan – Follow @janohistory

“GET out of my country” is what the white, Navy veteran Adam Purinton is alleged to have said before shooting and killing Indian Srinivas Kuchibhotla and wounding Alok Madasani in Austin’s Bar and Grill in Olathe, Kansas, on the evening of February 22, 2017.

A Sikh victim of a shooting on March 3, was also told to “go back to your country.” In the past few months, four Indians have been shot at, two fatally, sending shock waves through the Indian-American community. The 3.3 million Indian Americans have come to relish their reputation as a “model minority”. In 2014, the Smithsonian Museum feted the community through a special exhibit – “Beyond Bollywood: Indian Americans Shape the Nation,” highlighting the breadth and diversity of accomplishments of Indian Americans.

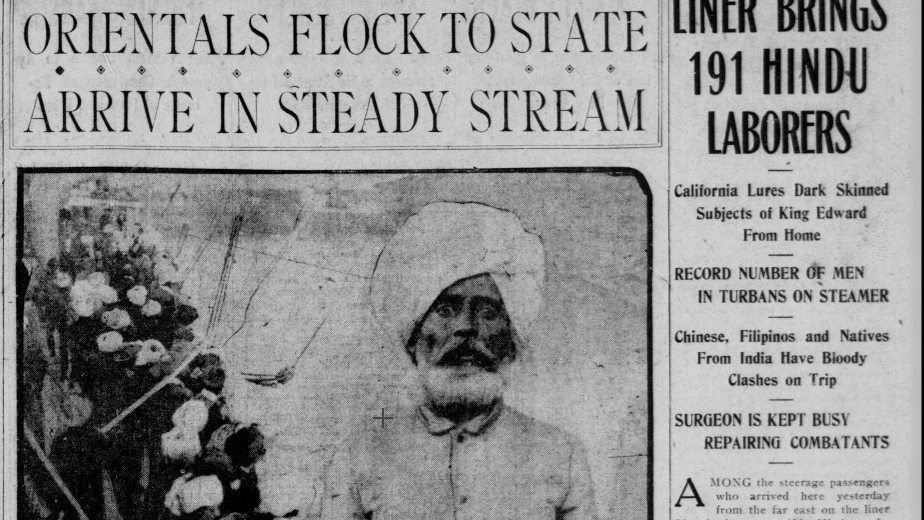

The Indian American story is a success story and desis and Americans alike flaunt it. It’s been easy to believe that America’s doors would always remain open to deserving desis. However, Indians are unaware that race and labor have coalesced many times in the past to influence and alter the nation’s immigration laws. Hostility toward “Hindu” immigrants was rampant at the turn of the century and immigration laws passed as an outcome of this hostility, stripped Indians of US citizenship and kept Indians out of the United States for 40 years.

Indians first started to arrive in the United States on the west coast in 1899. While they were primarily Sikhs, many Hindus and Muslims were included as well. India was under British rule at the time and Punjabis were, in effect, forced to leave in search of better prospects elsewhere. They were being impoverished by a colonial administration that imposed high taxes and forced this agrarian community to grow cash crops rather than food, to benefit the new industries of Great Britain. Punjabis, affected by drought and famine, looked abroad for better prospects. Many joined the British Army. Upon hearing of higher wages in America, several thousand Indians set out to find their fortunes in the U.S. over a period of about 20 years.

An article in the San Francisco Call on April 6, 1899, described the arrival of four such Indians:

“The four Sikhs who arrived on the Nippon Maru the other day were permitted yesterday to land by the immigration officials. The quartet formed the most picturesque group that has been seen on the Pacific Mail dock for many a day. One of them, Bakkshlied (sic) Singh, speaks English with fluency, the others just a little. They are all fine looking men”.

The Indian immigrants to both the U.S. & Canada (many went by ship to Canada’s Pacific coast) worked primarily as laborers in lumber mills and iron foundries. Many helped build the Western Pacific Railroad lines. Eventually, many Punjabis took up farming in the Sacramento, San Joaquin and Imperial Valleys of Central and Southern California. Between 1899 and 1908, about 150-200 Indians arrived every year. By 1910, a total of 4,713 Indian immigrants had come to America, including those who crossed the border from Canada (this number increased to 6,795 by 1920, by any accounts a small number).

The initial, bemused reactions to the Indian arrivals soon turned to hostility, discrimination, violence, and ultimately exclusionary immigration laws. Resentment toward the primarily laboring classes of Indians (as well as Japanese and Koreans) by the local European immigrant labor unions and leaders led to the formation of the Japanese and Korean Exclusion League (renamed the Asiatic Exclusion League in 1907). The stated goal of the Asiatic Exclusion League was to extend the Chinese Exclusion Act to all Asians. The Chinese Exclusion Act had prohibited the immigration of Chinese labor since the time it had been signed into law by President Chester Arthur in 1882. The law was repealed only in 1943.

On 14 May 1907, 67 labor unions including the powerful Building Trades Council (BTC) and the Sailors’ Union formed the Japanese and Korean Exclusion League. Based in San Francisco, the objective of the League was to bring about legislation to keep all Asian labor out of the U.S. Ironically, the leadership of the League were immigrants themselves. Patrick McCarthy, the President of the Building Trades Council was an immigrant from Ireland and Andrew Furuseth of the Sailors’ Union was from Norway.

The first president of the League – Olaf Tveitmoe – was also a Norwegian immigrant and the founding editor of the weekly newspaper, “Organized Labor,” the official organ of the States and Local Building Trades Councils of Califfornia. A letter from Olaf A. Tveitmoe, published in the April & May 1906 (combined) edition of the paper he edited – Organized Labor – states the fears and intentions of the League:

“The Japanese and Korean Exclusion League held its annual meeting Sunday and transacted its regular business as contemplated before the disaster.” (…)

“Attention was called to the fact that if it had not been for the efforts of the Japanese and Korean Exclusion League, assisted by united labor, the Foster bill would have passed Congress and thus the Chinese Exclusion Act would have been virtually repealed. It would have thrown down the bars and admitted every Chinaman to our shores who desires to come here.” (…)

“Thousands of fair minded and well meaning people who were biased and ignorant on the question of Japanese immigration have during the last year, entirely changed their views on the subject. They have learned the truth that the Japanese coolie is even a greater menace to the existence of the white race, to the progress and prosperity of our country than is the Chinese coolie. ” (…)

“The great calamity which befell San Francisco will furnish the Orient with lurid tales of opportunity for employment and profit. California, the land of fabulous wealth, revenue and mountains of gold, and San Francisco with its wonderful wages will be exploited before the ignorant coolies until they will come in ship loads like an endless swarm of rats.”

“Great as the recent catastrophe has been, let us take care lest we encounter a greater one. We can withstand the earthquake. We can survive the fire.”

“As long as California is white man’s country, it will remain one of the grandest and best states in the union, but the moment the Golden State is subjected to an unlimited Asiatic coolie invasion, there will be no more California.”

Shefali Chandan is an educator and editor of Jano, the online history magazine for Asian Indian families. She has worked for 2 decades in children’s media at organizations like Scholastic, Time Inc. and PBS Kids. Shefali has always been a history buff and now brings her extensive experience in education to craft high quality content taken from stories in history for South Asians in America and elsewhere. She lives in Reston, Virginia with her husband and daughter. You can reach her at editor.jano@gmail.com.

Shefali Chandan is an educator and editor of Jano, the online history magazine for Asian Indian families. She has worked for 2 decades in children’s media at organizations like Scholastic, Time Inc. and PBS Kids. Shefali has always been a history buff and now brings her extensive experience in education to craft high quality content taken from stories in history for South Asians in America and elsewhere. She lives in Reston, Virginia with her husband and daughter. You can reach her at editor.jano@gmail.com.