by Aradhana Gupta – Follow @browngirlmag

Author’s Note: The events following Indira Gandhi’s assassination on October 31st, 1984, changed views between Hindus and Sikhs in ways that are still felt today. Following is a first-hand account of my memories of those days from my memoir, “Beeba, The Good Girl.”

“We’ll all die someday. What difference does it make if it’s today or tomorrow? But I refuse to give up who I am while I’m still alive, I’m a Sardar and I intend to live like one until…”

Papaji said, with a crackling voice.

“Stop this cowardly nonsense.”

He tried commanding, but once again his voice gave away.

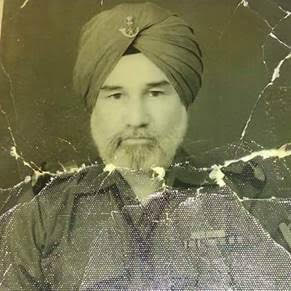

This resistance fit Papaji’s profile as a Sikh retired Indian Army officer. There was never a sliver of uncertainty that his love for India and pride of Sikhism were his only passions; they were his two eyes, and he couldn’t do without either one.

The country was in ruins by the evening of October 31st, 1984, just hours after Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination. The darkened mood of the nation was shrouded with blood stains and entombed in hatred. My heart brimmed with a yearning for what might have been had Indira Gandhi not been shot by her Sikh bodyguard.

“No Papa, don’t resist. We have to do this,”

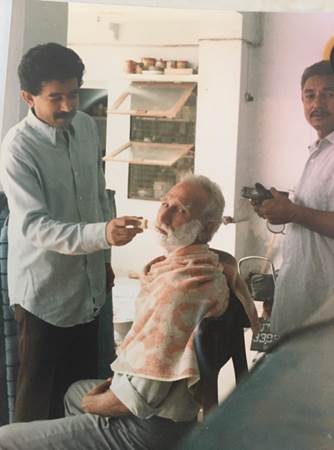

saying so, Tayaji irritably pushed Papaji into a stiff-backed dining chair, while Daddy forcibly held him in place.

“Papa, you better listen or we’ll have to tie you to the chair,”

threatened Daddy, patting Papaji with a slap on the shoulder.

Watching Papaji’s sons so harshly confine him to a chair, brought a flood of unending questions to my mind. I wanted to understand what exactly was happening, and why was it happening. All I knew was that Indira Gandhi was shot by Sikhs and there were blood feuds on the streets. We, being Sikh, were in mortal danger. We couldn’t risk stepping outside the gate of our own home.

In addition to this brutal chaos, I couldn’t make sense of whether or not to hate Daddy and Tayaji for depriving an old man of his lifelong Sikh identity or to admire them for being responsible sons. I had always seen these brothers in competition and verbal combat with each other. How could two brothers, who never saw eye to eye, collaborate so well when it came to stripping their father of his Sikh pride?

I felt ill and squatted onto the floor, loosely wrapped in a silk curtain made from a sari, as the room spiraled around me. Papaji’s resistance was feeble against his grown sons, and he had no choice but to surrender. At thirteen, I witnessed Papaji’s sons strip him of his five Sikh Ks. These five K’s; Kes, Kanga, Kara, Kirpan, and Kachh are the core of Sikhism, originated by Guru Govind Singh, our tenth, and last Guru.

In gaping horror, squatted on my haunches, I watched a long scissor zip through Papaji’s birth hair, dropping a white lock onto the floor, and then another. My heart throbbed with agony as I timidly observed the desecration of his first K, his Kes. In accordance with Sikhism, one vows to never cut bodily hair, Kes, but Papaji was forced to betray this vow. After his hair was chopped off and the beard was trimmed, his servant, Mali, glumly swept the tangles of Papaji’s severed Kes and condemned them to trash. Now it was the turn of the next K, kanga, a comb, which symbolized maintenance of the Sikh fetal hair, untouched by scissors. The kanga was broken in half and thrown in the dustbin with his discarded hair.

Next came the symbolic removal of the Kara and the confiscation of the Kirpan. Two more K’s gone! A Sikh’s Kara, a steel bracelet, worn on the right wrist is a reflection of Sikh oaths, as well as a visual reminder to restrain from evil. Kirpan, a dagger, an instrument signifying self-defense, was also discarded along with the steel Kara, as the two lay side by side shrouded with Papaji’s freshly orphaned Kes.

[Papaji: a proud Sikh and a Major in the Indian Army, in his younger days. Photo courtesy of Aradhana Gupta]

[Papaji: a proud Sikh and a Major in the Indian Army, in his younger days. Photo courtesy of Aradhana Gupta]

Papaji’s Pagari, ah, I remember it well. I can still feel its crisp starch on my hands, and remember its comforting smell from being wrapped around Papaji’s once long hair. But, it was of no use anymore. With the absence of his hair, the turban was purposeless, as a crown is without a head. Papaji had never allowed his turban to touch the floor or shoes. But now, it lay unraveled upon the floor by the dusty chappals, as a thing of the past. I watched as Papaji’s eyes flooded with tears that he refused to shed. I too, with tear-stung eyes remained speechless midst this unfolding world of horror.

Papaji was permitted only one K, his Kachh, the “soldier trousers” worn as an undergarment to promote freedom of movement as well as a reminder to control one’s physical passion.

[Papaji. Photo Courtesy of Aradhana Gupta]

[Papaji. Photo Courtesy of Aradhana Gupta]

Even through murky reception, the images of slaughter and fire were clear on the television, as a reporter informed about India’s plunge into devastation after Indira Gandhi’s assassination.

On November 3rd, the day after the massacre of Papaji’s Sikhism, neighbors who didn’t own a television, and servants’ families, spread out on the cold tile floor of the dining room to watch Indira Gandhi’s cremation at the Raj Ghat in Delhi. I too watched as her pyre flames raged, smoldering the nation’s peace.

I remember something about Operation Bluestar being mentioned on the television and over the transistor. Mama explained that this vicious circle of savagery was initiated by Indira Gandhi ordering the Indian Army to raid the Golden Temple at Amritsar, allegedly because Sikh separatist militants had taken refuge there and were hiding nuclear weapons.

“You know, Amritsar was my home. I grew up there and now it’s destroyed, barbaad ho gaya sabh. They entered our Guruduara with shoes on…can you believe it, with shoes on.”

Mama paused, put her hands together and mumbled a short prayer about forgiveness and then continued as she chopped coriander for chutney.

“They barged into a holy shrine, into God’s house with shoes, killing so many, even children… all because Indira suspected terrorists hiding there, but of course, kuch nahin mila, they found thing. Only dead bodies of innocent Sikhs were found. Chhi, may that woman never find peace.”

Mama quickly wiped her tears with the edge of her dupatta and went back to chopping.

I was stooped in shame for India. Approximately 400 innocent Sikh’s were killed in this bloody war. No terrorists were found, and the holiest shrine of Sikhs had been inhumanely violated. Indira Gandhi’s Sikh bodyguards gunned her down in retaliation. This resulted in a horrific backlash, as anti-Sikh massacres swept throughout India, with New Delhi and Punjab being the worst. The worsening conditions of India were reported on All India Radio, as we switched between listening to the news on our transistor and catching glimpses of the street riots on television, as long as the power did not go.

When finally the power did fail, as it frequently did for hours, especially during this plundering phase, we sat submerged in the yellowish glow of kerosene lamps discussing the downfall of India and the fate of Sikhs. At other times we sat in terrified silence by the dim candlelight, like stains of darkness. Papaji remained quiet, looking defeated. The shadow of those days never left him for the rest of his life.

“There was something about that woman I never trusted. I knew she’d ruin this country. It was just a matter of time.”

Mama had voiced her gut premonition during one of those lightless discussions.

Hours later when the power returned, the television resumed broadcasting the agonizing consequences innocent citizens were left to endure. During a radio broadcast, I heard that historical Sikh artifacts and literature were set ablaze by Hindu Indian officials. Sikh men were tied down with their forcibly unfurled turbans, as their wives, daughters, and sisters, anywhere from age twelve through sixty, were savagely raped before them. Some Sikh women slit their throats before being dishonored. Amritsar, the home of the Golden Temple was pillaged and burnt. Blood-stained walls witnessed uncountable Sikhs being shot and burnt alive in broad daylight.

Families were forced to abandon their homes or else they would be killed. They did as they were told and sacrificed their homes. Little did this matter. They were slaughtered on the streets anyway. Many took refuge in Gurudwara, but the Gurudwara’s too were ravaged and looted.

Though Agra wasn’t nearly as blood tainted as Punjab and New Delhi, the promise of slaughtering any man with a turban and beard still threatened the streets. In residential colonies, the bell of the milkman’s bicycle, as he rode down the streets delivering fresh buffalo milk, was no longer audible. Howling screams and faint gun shots in the distance had replaced this bell’s anticipated morning melody. The shrill call of the sabzi wala had stopped. All Sikh-owned stores were shut down, and if a Sardar dared to open his shop, he along with his shop was torched into flames. Schools were also closed since they were a prime location for abducting Sikh children.

Buaji, Mama, and I had to remove our Kara’s as well. Though my official name is Aradhana, on school assignments I used to write my name as Aradhana Kaur. This signified me as a Sikh girl. Likewise “Singh” pertains to all male Sikhs. Buaji, Mama and I had to refrain from being “Kaur.” These proud symbols of Sikhism had become a target for horror.

Pools of blood; gunfire; scattered, burnt and mutilated bodies; raging fires; curfews; adductions; rape; became India’s contour. The respect for Sikhs crashed worldwide. These lions of India, her protectors, and martyrs, were now considered the lurking phantoms of fear. Mothers grew paranoid and forbade their children to associate with other Sikh children. No longer was a Sikhni offered a seat on a crowded bus. Had India gone back to the seventeenth century when it was faced with the Mughal tyranny of faith conversion?

India’s inhumanity as viewed on television heard over the transistor, and seen spread throughout the newspapers left me deeply unsettled. Until then, I had spent my life ashamed of being part Anglo. The facts of British injustice caused my blood to steam. But, now, for the first time, I was mortified of being part Indian. I was revolted by the corrupted military and police. These officials watched their nation being ripped apart by its own people and did nothing. Political personnel filled their pockets with hefty bribes, hollowing them of basic humanity.

These repugnant images still resurface before me, as my mind hears the cries of the orphaned children’s echoes. Had I not seen the horror of all horrors when I had watched the rape of my grandfather’s Sikh dignity, the only identity I had ever known him by?

On the morning of November 4th, I heard Papaji wake up earlier than usual. Curiously, I tiptoed behind him, trying to rub the sleep out of my eyes. He lugged himself into the courtyard and stood there for many long moments inhaling the beauty that had now faded of the tricolored Indian flag and the saffron-hued Sikh flag, as they danced side by side, bathed in dewy tears from the heavens. Many silent minutes later he straightened his spine in attention, and then stomped his feet together like he had in the Indian army, and saluted the flags. Papaji stood at attention, saluting, for a long while as he memorized the flags’ glory before separating them from the pole forever.

My grains of sleep were quickly replaced by thick tears as I watched Papaji pull down the two flags that I had grown to love in Mama’s courtyard. Just a moment ago what stood as the present, now lay in a dark box as history, leaving behind two empty poles that no longer had a purpose. Both flags were folded and put away into a closet, never to be unfurled again.

Aradhana Gupta is a Sikh Anglo-Indian born and raised in India She pursued her education at Rutgers University. She currently resides in the United States where she is raising her two sons. Writing is a cathartic release for Aradhana. She has examined her life of abuse and survival in her multi-cultural memoir, Beeba: The Good Girl, which she is aspiring to get published. Aradhana is also a certified Yoga instructor and maintains her own multi-lingual poetry blog. She is passionate about sharing her stories of life growing up in India, as well as the adversities she has faced in America while raising two brown boys.

Aradhana Gupta is a Sikh Anglo-Indian born and raised in India She pursued her education at Rutgers University. She currently resides in the United States where she is raising her two sons. Writing is a cathartic release for Aradhana. She has examined her life of abuse and survival in her multi-cultural memoir, Beeba: The Good Girl, which she is aspiring to get published. Aradhana is also a certified Yoga instructor and maintains her own multi-lingual poetry blog. She is passionate about sharing her stories of life growing up in India, as well as the adversities she has faced in America while raising two brown boys.