The following post is originally published to SurjMagazine.com and republished here with permission by the author.

Brown boys my age engage in the most violent projections of the patriarchy. The diaspora in New York City represents a microcosm of south Asia — its vibrancy, its colorful culture — but it rears the ugly head too often, whether it be divisions of religions, nationalism, or of course, a very carefully constructed misogyny. It doesn’t come from Islam, and yet religion is used as a defense from accountability. It doesn’t come from Hinduism, and yet tradition is used as a facade to get away with it. Stop using God as your security blanket to justify your suppression of women. It has stretched from our homelands that are desperately trying to reform to no avail.

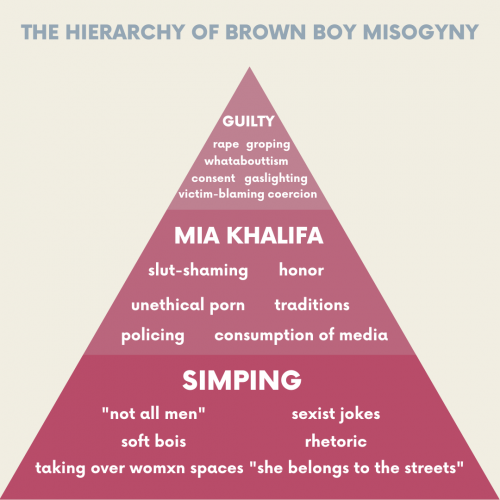

I’m going to break this down into three sections: guilty, Mia Khalifa and simping to make it easier to comprehend. It’s like a pyramid, top to bottom — the hierarchy of brown boy misogyny.

I. Guilty

In the past week or so, brown girls in New York City have been coming forward in what can be called an intense second wave of the #metoo movement. This time, it’s coming for the brown boys who thought that our culture’s taboos would keep them safe. It’s not just random brown men either. It’s friends, it’s classmates, it’s family, it’s Khan’s tutorial. accounts like ‘telling my truth,’ which was the first to go viral, are anonymously sharing the victim’s stories and urging their followers to hold the brown boy accountable for his actions. and they’re listening: In the past two days alone, there are thousands of comments tagging the said perpetrator’s school and employment in an effort to call attention to the specific story. Although telling my truth has now been deactivated, to be a survivor and anon.co17 are still actively posting stories.

[Read Related: Madame Gandhi Envelopes us in Her New ‘Visions’ Energy and it’s Worth Every Minute]

However, in classic brown culture style, we have men and even women deflecting the issue, but let’s be honest, did we expect anything else? Instead of cutting ties with known rapists, these people are insisting that somehow it is still the girl’s fault. She was drunk. She was showing skin. She was hanging out with a guy late at night. “It’s haram,” they say. But what about forcing yourself onto someone? Is that not haram, too?

Prophet Muhammad (saw) swiftly punished a rapist when a woman came to him. He did not try to convince her otherwise, he did not blame her, so who are you to gaslight a survivor? There is no link between rape and sexual desire. don’t tell us to dress better — become better men. When the stories started to gain traction, brown boys claimed that these girls were ruining the man’s reputation. Did you not stop to think that he ruined her in every way imaginable? And what reputation are you talking about? Instead of standing with the victim, you’re out here defending your boy and asking her what she was doing. Who cares what she was doing? We know what he did.

Over and over again, we are seeing the brown boys named defending themselves by insisting that while they are definitely assholes, they are not rapists. They’re saying they had consent from someone who was drunk. how dare you. How do you expect someone who is intoxicated to give you the same answers as she would if she were sober? You were waiting for her to be drunk enough to have your way. Their excuses are: “She was wet, too!” “I know she wanted it.” “She was feening for me.” “She’s a clout-chaser.” “She continued to be friends with me after I did it.” “How come she didn’t report it to the police?” “How do you not know when you were being raped?”

Their pathetic excuses won’t work on us. Tell me, do you know that physical arousal isn’t consenting? If she wanted it, why are you so scared? Was she really feening for you, or are you gaslighting the trauma you caused her? I hate to be the one to ask, but tell me, what clout could a rape survivor possibly get when our own president is a rapist? Since you’re so smart, you must know that thousands of rape kits go untested at police stations, right? You must know that police do nothing to protect women. and you, of course, know the lengths a brown family would go to convince their daughter not to report her abuser. It is not the job of brown girls to educate you on how survivors process rape differently; there is no ‘correct’ way to react after being assaulted. But since I’m on the topic anyway, let me tell you that 70 percent of rapes are committed by someone known to the victim and continuing a relationship with an abuser is a common way of repressing the memory. It does not, in any way or form, negate the fact that the rape happened.

It is not the job of brown girls to educate you on how survivors process rape differently; there is no ‘correct’ way to react after being assaulted.

And the friends of these boys? They’re defending them. They’re writing love letters in their DMs as proof of character. News flash: Just because he held the door open for you once in third grade doesn’t absolve of him of rape. Brown boys have collectively come together to force the victims to prove their rapes countless times. One girl even had to screenshot her rapist’s “apology” and refuted every single thing he said because he tampered with evidence and screenshots. Brown girls don’t owe it to anyone to prove a single thing, yet they’re being pressured to do so, thus reliving their trauma under a harsh spotlight. These are brown boys that we might not know personally, but they run in our circles. We have heard these stories before. It could have been any of us, and it is imperative to stand up for all brown girls. break the damn bro code. Call out your boys.

Our culture downplays sexual assault because we are trained to believe that men are in control, and even if we know that men are the problem, we place the blame onto women because brown girls should compromise, be careful, and protect themselves. The shortcomings of brown men are somehow still our fault and ours to fix: jab iski biwi aayegi, toh yeh sudhar jayega (when he gets married, his wife will fix him). we rarely teach brown boys to not rape; we don’t teach them the word no. We let them get away with so much, and it culminates into an explosion like the one happening right now. Our culture already makes women so vulnerable from the very moment they are born. The very first thing we’re told to do is close our legs, sit like a lady, cover ourselves. brown girls are already guilty from the time we enter this world. This is the very same reason why it is so frustrating and difficult to even say anything against an abuser, predator, and rapist — we are told to keep quiet because it won’t get anywhere.

Our culture downplays sexual assault because we are trained to believe that men are in control. We place the blame onto women because brown girls should compromise, be careful, and protect themselves.

And the thing is, it doesn’t start with rape. men view rape as aggressive, forced upon sex, but ignore the cat-calling, groping, and casual touches we deal with while we walk down Sutphin Boulevard in Jamaica, Queens. I don’t know who needs to hear this but saying “mashallah” won’t cancel out the fact that you tried to grab a girl’s ass. Every time I try to explain rape culture and its consequences, I am hit with the same answer: “I don’t care, it’s a joke.” These are the same boys that turn around and victimize themselves when they are finally called out for their extremely perverted behavior. Rape is not limited to extreme force, and brown boys are the quickest to victim-blame. Save for a select few, so many brown boys are now saying that there are two sides of the story and that we should all wait for evidence — were you not paying attention? How much more evidence do you need? If your first instinct when hearing about sexual assault is to automatically discredit the victim, or start to talk about how women “lie,” — as if that false equivalency even makes sense — unlearn your own misogyny. Growing up in a close-minded household isn’t an excuse to not educate yourself. Brown boys fail to keep this same energy for the 98 percent of rape allegations that are true while hounding to death the 2 percent that are false.

I don’t think it’s just our culture that’s failed us for being inherently insensitive to gender-based violence — it’s also the men. They lack empathy, they lack remorse, and they want us to “stop the cap.”

II. Mia Khalifa

Brown boys are more often than not desensitized to violence — baba beats ammi, he slaps your sister across her face, but he doesn’t hit you because you’re a mard (man). You may get angry at him and shout at him to stop, but the violence seeps into your veins. It runs through you so viciously that you watch media that inflict violence upon women, and you don’t even notice — be it your video games, the Netflix shows you watch, and the unethical porn that you consume. Suddenly, all the sharam (shame) that you speak of dissipates.

Let me make it a tiny bit more specific: Let’s talk about Mia Khalifa. Let’s put a pin in the conversation about Islamophobia and her Lebanese forces cross tattoo — yes, the same armed forces who allied with the IDF and led the sabra/Shatila massacre. It was not her active decision to partake in hijabi porn although it disrespectfully sexualized Muslim women, and sure, let’s hold her accountable for calling the scenes satire, but let’s not pretend that’s where the sexualization of Muslim women by brown men started.

[Read Related: Why Dismantling Patriarchy is Good for Men]

She was coerced into her contract with Pornhub during a low point in her life years ago and was never compensated properly. Pornhub refuses to remove her videos, but brown boys don’t know that. All they know is that she’s the ‘Muslim’ girl from porn and crack a joke about her every time they see a brown girl wearing glasses. She lost her family, she doesn’t get a second chance at first impressions and gets shamed every day because brown boys have an extremely exploitative obsession with her. You call her a disgrace, but you actively watch her videos — special shoutout to Muslim-majority countries for always ranking at the top for porn consumption — and then take pleasure in picking her apart in your little locker rooms. And it’s all because you have been taught — and you choose to believe — a twisted culture that allows you to belittle any woman for any reason. Brown boys have the audacity to say that she chose to do porn, that it was her fault for ignoring how our traditions work, and then say it’s not a respectful job to have. Why does it irk you when girls profit on their own sexualization?

- Learn the difference between coercion and consent, and

- Our traditions are deeply rooted in the patriarchy — brown girls are not bound to them. Sex work is valid work, you can acknowledge that while still knowing that porn is violence against women. Both exist at the same time because rape culture is so normalized in our communities.

Slut-shaming is especially prevalent in our communities; brown boys love calling brown girls hoes, feens, and sluts for existing. Everything we do is a threat to their izzat (honor). Brown boys will get off to naked women on their screens and then go tell their girlfriends and sisters what to wear. They police the women in their lives because they know that all men are, indeed, trash. they know because they happen to be one of them. You tell your sister to wear her dupatta (scarf) because you are the same man who looked at a woman lustfully as she walked down the street. You tell your girlfriend to button up her shirt because you know how predatory the male gaze is.

You tell your sister to wear her dupatta because you are the same man who looked at a woman lustfully as she walked down the street. You tell your girlfriend to button up her shirt because you know how predatory the male gaze is.

III. Simping

The simplest form of sexism — and I say “simplest” lightly because it is incredibly harmful and helps in climbing the sexist mountain — is literally rhetoric. Our generation has a lot of good things going for us: We advocate on TikTok, we take care of our mental health, we’re pretty woke. But for some reason, we’re the same generation that let go of cigarettes (only for nicotine in a USB instead) faster than we let go of slut-shaming. Brown boys don’t realize that slut-shaming doesn’t have to be heard; it’s not just cat-calling or calling a girl a whore to her face. You just have to laugh at the rape joke your boy just told. You just have to turn a blind eye to your friend cheating on his girlfriend. You just have to say that she belongs to the streets. Think of what that means. You think just because a brown girl shows some skin, just because she is sexually liberated, and just because you can’t stand the fact that you can’t have her that she should be thrown out? It’s not just a joke. It’s suggestive of another ideology at play. Brown boys will do the same things that they think is “hoe behavior” but will never apply this double standard to themselves. Because they know they are immune to any type of backlash. so if “simping” means respecting women, then so be it. Be a fucking simp. Stop being nice to girls you want to sleep with and then throw all moral decency out the door. You belong to the streets, not the girl who rejected you.

[Read Related: Traveling the Long Road From Patriarchy to Freedom]

Some brown boys hide their own sexism behind a soft boy persona. You can brand yourself a leftist and be an ally, but that performative behavior doesn’t do anything when you’re only doing it to appeal to women. You’ve built your base on the free labor of your female friends who taught you all the right things. The subtle sexism that exudes from self-labeled soft brown boys is typical — it’s quiet but it’s seething. You support your girlfriend being a feminist, but you want her to hold your hand while she’s saying men are trash? That’s not how it works. you are not exempt. You’ve done the bare minimum for women, congratulations.

That performative behavior doesn’t do anything when you’re only doing it to appeal to women. You’ve built your base on the free labor of your female friends who taught you all the right things.

So many brown boys like to speak over women because they think it’s a personality trait to be sexist (and they like that their friends cheer them on for it). Brown boys have made up their minds that women’s struggles don’t even exist, so how can we ask them to be educated? You can’t sit here and tell us what you think real feminism is — don’t you dare talk over those who are trying to create change within this stubborn society. You say that “men need to do better” but put in zero effort to make the women you know comfortable. You don’t get a cookie for thinking you’ve never been even moderately violent towards a woman. Because chances are, you have, and your girlfriend ignored it because brown girls are told to compromise since isli mard aisi hi hotay hai (that’s just how boys are). Say it with me: Being nice to your mom, girlfriend, and wife isn’t being a feminist. If you still hate the ones that you think stepped out of a line set by the patriarchy, you’re a misogynist.

Thank you for coming to my TedTalk.

When brown boys are born, they suddenly become the center of that household, even with daughters — and yet Islam preaches the exact opposite. brown boys are coddled; they are taught that they can do anything, and they will still be defended. They are told that a woman is something to step on for their own purposes. In the city where it seems so easy to be educated and respectful despite growing up in such a household, brown boys aren’t, and they refuse to be. They want their girlfriends and wives to exist solely for them because that’s how their parent’s relationship worked. Brown boys are quick to deem this as an unnecessary gender war because nothing affects them. It’s because you don’t care since you think you’ll continue to get away with it. Well, I’m here to tell you that you won’t.

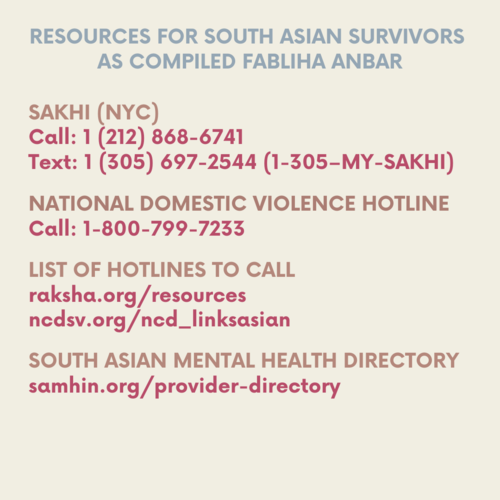

To South Asian survivors seeking resources, please access the following links and numbers below.