Below is the second installment of the Brown Girl Magazine “Bollywood Social Consciousness” series, where we will examine our favorite B-Town films through a contemporary social lens.

It’s no secret that India has come under glaring international scrutiny with respect to sexual violence. This scrutiny has resulted in the bifurcation of interested minds—while some recognize the grim realities of sexual violence and speak out against the institutions that perpetuate them, others remain in denial regarding its significance by asserting the red herring argument that India is not the exclusive home of sexual violence, therefore, there is no need for heightened Indian scrutiny.

Quite famously, a journalist criticized Mallika Sherawat in 2013 for speaking on an international platform about the issues that Indian women face both culturally and systemically. The journalist’s criticism was incited by an ideology with which much of our BG readership is familiar: shame culture. Mallika was criticized not because of the accuracy of her statements about Indian society being regressive for women, but because she essentially made India look bad. The very stuff of log kya kahenge (what will people think?) that has been stifling valuable discourse with respect to social justice and cultural reform in many pockets of the world.

[Read Related: Mallika Sherawat Destroys a Female Journalist]

Although Mallika aptly rebutted this assertion by explaining that she simply would not lie about the regressive state of Indian society—evidenced by alarmingly high rates of female infanticide, honor killings, and sexual violence—I remained bewildered by this assertion that such issues should not be discussed on an international platform so that India’s reputation can remain unscathed. As though this is a bad report card that your parents want to keep a secret from your nosey aunts and uncles.

Concededly, it is true that India has no monopoly on sexual violence and that this issue is certainly one that ensues in its most horrific forms throughout the world. However, the realities of the disposition of women in South Asian societies, (and how these realities directly contribute to both misogyny and an evidently thriving rape culture), cannot simply be concealed for the sake of avoiding perceived international humiliation.

It is also of no benefit to dismiss these issues simply because they happen in other cultures as well. Resultantly, it is from the spirit of Mallika Sherawat’s commitment to truth that this month’s Bollywood Social Consciousness Series was conceived. What does Bollywood—the largest film industry in the world, consumed by tens of millions of viewers—teach us about rape culture and consent?

[Read Related: Is Bollywood’s ‘Khabi Khushi Kabhie Gham’ Socially Conscious?]

To be clear, rape has never been outright glorified in Bollywood and Bollywood did not birth rape culture. However, other behaviors that breathe life into rape culture are normalized over the 3-4 hours that it takes to get through a single film. The incorporation of item girls, for one, has been extensively discussed as one of these behaviors.

Item girls are essentially hypersexualized women, who appear mid-film for extremely racy dance numbers while male background dancers drool over them. These dance sequences, and their corresponding item girls, generally carry no significance with respect to furthering the plot of the film and involve tiny outfits, copious pelvic thrusting, and a sea of sexually entitled men. Ironically, Mallika Sherawat is one of these famed item girls. Awkward.

[Photo Source/Tumblr]

[Photo Source/Tumblr]

Now, women are entitled to their sexual agency. Wearing tiny outfits and reveling in being a sexual being is not the obvious issue with these illustrations. What is at issue is the behavior of the men in these songs that convey an overarching message of male entitlement to the female body.

These songs communicate that when a woman does choose to embrace her sexuality, it is for the pleasure of her male counterparts—the age old she was asking for it mentality. This normalization of male dominion over women in film lends itself to the daily menaces of eve teasing and harassment. Behaviors that can render a society inhabitable for its women.

There is a far greater evil, however, other than hypersexualized item girls, and that is the hypermasculinity that is devotedly attached to our Bollywood heroes. Men in Bollywood are seldom portrayed as anything less than aggressive and violent machismo oozing with excess testosterone, all while fighting off ten men with their bare hands and keeping their gelled hair in place.

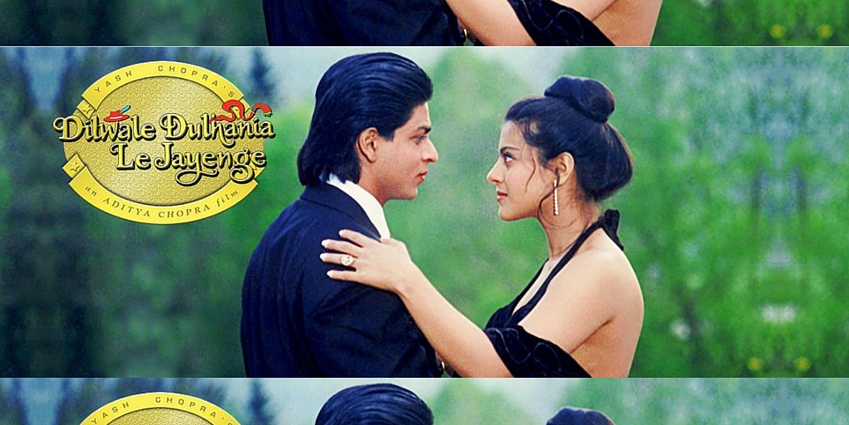

The cult classic “Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge” (DDLJ) exemplifies this depiction of glorified violence. When Shahrukh Khan’s character, Raj Malhotra, is first introduced in the film, the patriarchal implications of optimal manhood practically burn your eyes like acidic projectile vomit. Raj can outrun both a soccer team and a small plane. He swims, wins car races, and bowls straight strikes. In the film’s closing scenes, he is successful in thrashing a crowd of men within inches of their lives. He is the patriarchy’s wet dream and this is a dream that has been recreated a hundred times over in the Bollywood canon.

[Photo Source/Tumblr]

[Photo Source/Tumblr]

These repetitive depictions of masculinity paint a picture that equates manhood with violence and this violence and hypermasculinity largely translates into staggering high levels of violence against women in South Asia. If our cultural expressions legitimize these behaviors, why wouldn’t they infiltrate the basic tenets of daily life? The conflation of manhood and aggression is also extremely damaging to our men, as this sires tormented developmental years in pursuit of these unrealistic and outrageous masculine standards—a guaranteed byproduct of the patriarchal agenda.

The matter of consent interacts with these aforementioned hypermasculine behaviors for a dubious cocktail legitimizing rape culture. And in this culture consent means nothing. Nothing quite encapsulates this cinematic translation of steep social regression like “courtship” songs. We have all witnessed those musical segments in Bollywood films devoted to showcasing how the hero courts his lady. We have all probably enjoyed them, hummed them, and maybe even performed them for our third cousin’s sangeet. And yet they are the most nefarious instances of complete disregard for consent.

The hero follows the object of his desires. She shouts at him to leave her alone. He grabs her arm. She pushes him off. He forces her into his arms. She struggles out of it. In some films, his group of friends join in on the harassment and entrap her further. Yet somehow after this de facto molestation, the film has found a way to make this abused woman fall in love with their hero, thus imparting the harmful false truth that “no” doesn’t really mean “no.” Instead, a woman’s lack of interest is simply a challenge for a man to overcome, just as Shahrukh overcame the crowd of fighting men. This screams that if a man is proactive and consistent, he will conquer the woman he desires.

Courtship songs thus teach Bollywood’s male viewership that consent is theoretical. A theory that can be deconstructed with enough tenacity and stamina. Even worse, offensive displays like these are often packaged as comedy—something to laugh off heartily and not to be accepted as legitimate mechanisms for informing social behaviors. To return to our cult classic, DDLJ painfully jokes about rape immediately after the jovial “Zara Sa Jhoom Loom Main.”

In this scene, Simran wakes up with the mother of all hangovers and Raj thinks it would be funny to lie about taking advantage of her while in her chemically induced comatose sleep.

[Photo Source/im.hunt.in]

[Photo Source/im.hunt.in]

This irresponsible dismissal of the necessity of a woman’s consent epitomizes the groundwork for the diseased male privilege and the related rape culture that continues to thrive in South Asia.

As a result of these grim realities, South Asian women are heavily surveilled by their families throughout their lives, as it is easier to teach our girls how to prevent themselves from getting raped than it is to teach our boys not to rape them. The latter is concededly a hard lesson to teach when the world’s largest film industry teaches men that they have birthright ascendancy over the female form.

Again, Bollywood certainly didn’t conceive rape culture and all of its patriarchal implications. However, it does serve as a potent medium through which these behaviors are exaggerated and glorified on the big screen for mass consumption. Sex aside, rape is about power. And these films markedly and directly endorse the notion that male dominion is the climax of masculine power, thus necessitating heightened aggression toward women.

In order to break down the cultural structures that preserve regressive societies, our arts must emulate a more obliging depiction of love and romance—free of the glorified violence against women that has become normalized in our cultural consciousness. In order to inspire a change in our arts, we must be able to discuss these issues openly without fear of the proverbial shame that Mallika Sherawat was accused of inciting.

Rape culture is a lucrative venture. The masses fund these productions, all with their racy item girls and problematic courting techniques. It will only cease to be lucrative if, as a collectivity, we demand responsible cultural commodities—an ideological conclusion that is inspired by the concededly flowery doctrine of supply and demand. Without our voices, stagnation will reign over potential cultural progression. And our Brown girls around the world will suffer because of it.

Elizabeth Jaikaran is a freelance writer based in New York. She graduated from The City College of New York with her B.A. in 2012, and from New York University School of Law in 2016. She is interested in theories of gender politics and enjoys exploring the intersection of international law and social consciousness. When she’s not writing, she enjoys celebrating all of life’s small joys with her friends and binge watching juicy serial dramas with her husband. Her first book, “Trauma” will be published by Shanti Arts in 2017.

Elizabeth Jaikaran is a freelance writer based in New York. She graduated from The City College of New York with her B.A. in 2012, and from New York University School of Law in 2016. She is interested in theories of gender politics and enjoys exploring the intersection of international law and social consciousness. When she’s not writing, she enjoys celebrating all of life’s small joys with her friends and binge watching juicy serial dramas with her husband. Her first book, “Trauma” will be published by Shanti Arts in 2017.