by Jason ‘Jayology’ Jeremias – Follow @pos_theatre

The following post was republished from Indus Daily with permission from the author.

I woke up this morning next to a rape survivor. She was preparing for her first day in a new position. It would seem like a celebratory time. I looked at her getting dressed in the new clothes she bought for this special occasion, while she pointed out the parts of her body that she wasn’t happy with. I pointed back how great she looked in her confident resilience and excitement for the gauntlet she was about to run.

After all, she survived to live this moment.

Not only did she survive her rape, as if that alone isn’t painful enough, she survived the rape aftermath. The war that is fought every single day in memories of the ordeal of waking up and surviving that first morning, the morning after she was raped.

She survived going to the hospital and having a rape kit done. She survived climbing that mountain of sterile anxiety up to the police precinct in New York City, alone, where a detective told her that if she could get her rapist to maybe send a message, or corroborate her story, they might investigate. They might investigate. If she couldn’t get her rapist to corroborate, then she could be arrested for harassment. Is that a gamble you want to take right after living through the unthinkable? Imagine…a man robs a store, but the thief doesn’t corroborate the story, so the owner is arrested. Sounds unthinkable, unless you have survived rape in the United States. Yet this is the upside-down world of so-called justice that women wake up to survive every day. And today, she was surviving knowing that for her there would never be justice.

Justice would have been not being raped, because it isn’t a store, it’s your physical being. It is the murder of autonomy and physical self-determination. It is the genocide of agency. You think invoking “genocide” might be going too far. You might reserve the word “genocide” by its legal and international normative standard. Yet, how many women’s agencies must be invaded en mass, self-determination murdered annually, to confront this reality and turn the world right-side up in the direction of women’s inherent dignity?

Yet she survives and so does her dignity, unscathed.

Unscathed despite seeing her rapist on the cover of New York Time Out. She survived and survives. She survived the seconds of panic attacks, anxiety attacks, crushing depression, and dissociative episodes where seconds are infinities. She walks that tightrope between falling off the edge of a world that offers no comfort and she remains. These battles aren’t a one-time war, they are daily fights. Losing one can mean anything from plummeting into spirals of depression, where tides yank the entire consciousness out into the middle of the ocean, to drowning where there is no more waking up, no more surviving.

This, these words, they are not one of those celebrity male feminist “hey guys we need to be actively involved in this battle” mantras that trend for a day, then disappear till the next one appears on social media after the next woman who the media chooses to care about has been raped. If this rally cry hasn’t been muddled and muted by industries constructed to make media, where fights to end a culture should exist in definitive actions, urgently needed, which they haven’t, we will loose the humanity of a generation.

Never before has rape culture been so conspicuously illuminated to a generation, nor has it ever been so damningly placated to by false demagogues of industries and institutions who perpetuate it. You have to love the comedian who speaks to women’s equality on the late-night talk show, but then refers to women as “bitches” in his set. You have to love the so-called industry recording artist who speaks at the political rally, but then refers to women as “hoes” in his recording. You have to love the activist who speaks in glaringly powerfully academic terms in Tweets but then laughs at the comedian and dances along to the recording artist because they just like the beat. You have to love the politician who acknowledges that rape is part of our culture – our national and global culture of inhumanity that targets more than half of the human population in terms of statistics of violence and mortality that make any plague, health crisis, and conflict seem like improvements in the human condition when measured against violence against women.

I wonder, if apartheid in South Africa — fought tooth and nail, life and death, sustained action and movement, rally after rally, boycott after boycott — were fought as passively as gender and sexual apartheid are being fought, how much worse the indigenous peoples and tribes of South Africa would be today?

Yet she survives gender apartheid and sexual terrorism. She survived this weekend in a hospital bed. Her unconscious body murmuring, “Don’t let my rapist get me…” as confused nurses looked on trying to offer comfort. She survived looking in the mirror and through the memory that incessantly haunts her reflection of looking in the mirror after that night. She survived the shower. She survived the shower again today. She survived, but the scratches were traced down the memories of her skin where she scrubbed so hard, too hard, as to wash away those memories.

Last week at work she received a phone call. A man who, in all his inadequacy, thought it fun to reply to her “can I help you” with “you can help me rub my d*ck.”

How triggering that must have been. In fact, I know how triggering it must have been because I got the message, “There’s been an emergency.” Unconscious in the hospital, but she’ll be okay. The x-rays show no organ damage. Her vitals are good. Though what is going on in the parts of her that the most sophisticated imaging machines can only show in waves of activity?

This is the brutality of rape not shown, not recorded, on popular blogs by male celebrity activists.

No words can measure the energy of courage against the weight of currents when she places her feet down on the floor to start her morning. Good morning, I survived.

She strides. She strides as a woman of color. She strides as a Muslim woman. She strides as a powerful advocate. She strides as a human being. I sit back and smile, not relaying all of this, just in love with her resilience, her determination, her intellectual and emotional intelligence, as she embodies in her unique and only life on this earth a lineage of historical memory of masses of women’s experiences.

I, as a man, cannot begin to comprehend this marrow that is the only real determining chromosomal difference between her humanity and man’s humanity, my humanity, or inhumanity.

This isn’t one of those “I woke up next to a rape survivor, pat me on the back, let’s confront the stigmas” rant. I am not sure if I correspond my position on that thesis that the editors will publish these words, but in the spirit of womankind, fuck that.

I am the lucky one. We are the lucky ones. Our “luck” though, while conflicted by “man-made” battles of mazes of historical oppression in privileges of economic status, tribal affiliation, caste, race, and birth-determined locations of our existences, can never comprehend the determination of the existence of woman within these intersections and outside these intersections.

Imagine opening your news feed once a week to millions of men having their sexual organs cut off, sewn shut, so they wouldn’t engage in sex outside of marital “bonds,” so that they will be pure for their wives, wives who will be chosen for them. That sounds outrageous to the point of not being publishable, but when it’s a girl or a woman, it’s to be expected.

Rape affects men is its own thesis, but I guarantee you, if it were a pandemic of mass proportion the way it targets women without distinction of “man-made” and socially designed borders, it would have promoted a type of unity in man unprecedented to human his-story. There would be a holy war the likes of which would end every single so-called sacrosanct tenet of man’s entitled history in social lingua. If words give birth to perceptions of dehumanization, and dehumanization ushers violence, and the linguistics of misogyny were conversely inverted to describe man—Sharmuuto, Gintu, Slet, Slut, Bitch, Hoe, Kutya, Zona, Prostitute—they would be devalued from the sociocultural and economic depositories of masculine capital.

It’s amazing how, in a unique and diverse world of so many identities and languages, man’s lexicon of violence against women is so diversely the same. Guarantee you though, as a man, if these words could in any way be associated with mass unprecedented violence against man, you wouldn’t find man “reappropriating,” nor finding these words as empowerment. You wouldn’t see them re-circulated into entertainment. We wouldn’t be searching for the lowest common denominator to the problem, we would be looking for the consummate solution. We would have found the consummate solution in the reflection staring back at us in the mirror of inhumanity that is our own reflection of cultural agents of misogyny.

We don’t though. We don’t because we don’t wake up as women. We don’t think—as we shout the lyrics, sing along, dance to, reenact the porn we consumed, embodying Bollywood and Hollywood film bravado, the street capital to the boardroom capital, the street harassment to the workplace harassment and every single space in between insulated with microaggression and all out violence.

In the years I have worked, from my place of privilege as a cisgender male in efforts to end violence against women, I have read and discoursed so many theories. I have organized on the streets and spoke in classrooms. I have worked in art spaces and collaborated with women from around the world. I honored the term survivor as a distinction of courage. I have empirically noticed and noted the more than a conspicuous reality that when mass injustice against a girl or woman happens locally, you never, NEVER, ever see man respond the way women respond when injustice targets man. Not in the his-story of movements have we, as a gender, ever responded to a single woman with the response that women have historically responded to the cause of man. It is this reality that the term survivor became a distinction of empowerment and courage. Yet it wasn’t until I woke up next to a survivor that I became aware of what it means to be a survivor. What I have learned is that I will never know.

Thank you for allowing me into your world. Never stop surviving.

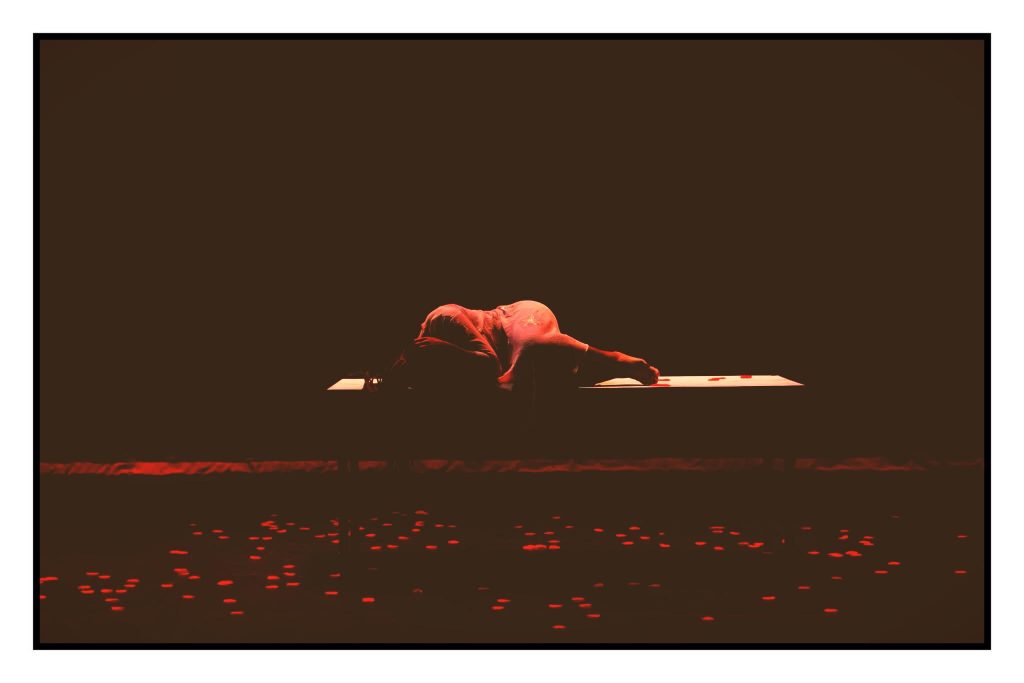

Jason ‘Jayology’ Jeremias is the artistic director of the performing arts collective for women’s rights, Price of Silence. Price of Silence is a grassroots performing arts company bringing the global struggle forged by women for equality to life on stage and action to the streets.

Jason ‘Jayology’ Jeremias is the artistic director of the performing arts collective for women’s rights, Price of Silence. Price of Silence is a grassroots performing arts company bringing the global struggle forged by women for equality to life on stage and action to the streets.