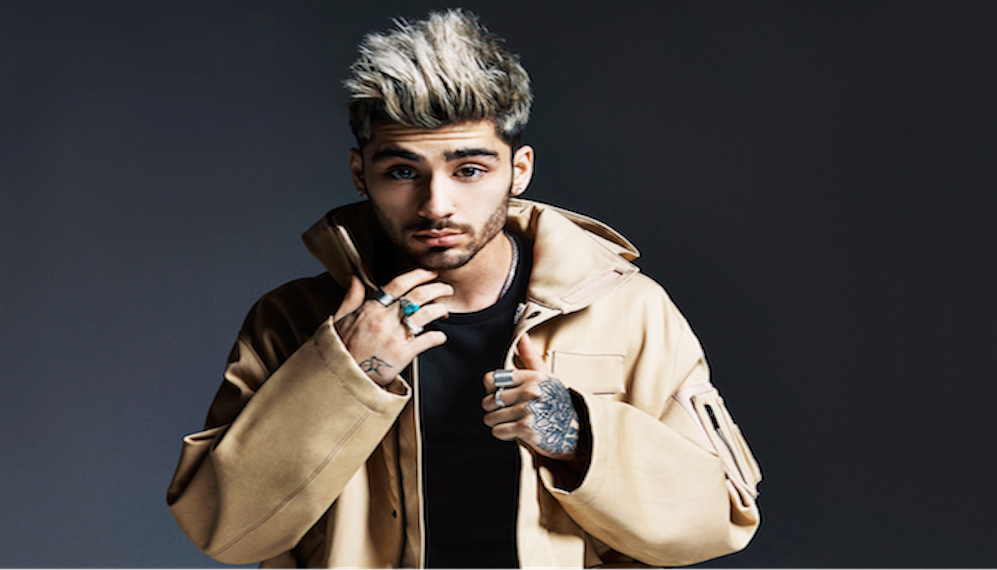

Since his ascent to boy band superstardom, Zayn Malik has consistently been defined by his faith, above all else, in mainstream media. The multi-faceted and complex identity of a mixed race, young, British male was watered down to a single signifier: “Muslim.”

Like all manufactured boy bands, the members of “One Direction” fit the typical cookie-cutter stereotypes. If Harry Styles is the heartthrob lead vocalist (aka, the one who can sing), Niall, Liam and Louis occupied their own spaces in the cookie tray. As a result, they were embraced by, and allowed to flourish within, the boy band paradigm. Malik, on the other hand, did not fit this mould. A heartthrob in his own right, and arguably the strongest vocalist, he was not afforded either role within the group. Instead, he was labelled “the mysterious one,” doublespeak for “the outsider,” “the one we don’t understand,” “the other.” The Muslim. To borrow from Boris Johnson, the band’s white members were “culturally the same” as their target audience (i.e., white UK and America), and thereby a cohesive unit. Malik, with his Arab name, brown skin and reluctance to dance, was destined to remain on the periphery from the very beginning.

A naïve Bradford teen suddenly thrust into the strains of fame, Malik initially wore his religion on his sleeve. He sent out tweets with Eid wishes, discussed Ramadan and proclaimed the Shahadah. These were not political acts — these were the embodiment of an 18-year-old British-Muslim boy narrating his life. But once spoken into cyberspace, we forfeit ownership of our words and the intentions behind them. Malik’s open declarations of faith catapulted him to “Muslim icon” status for millions of Muslim teens who, in him and his words, found the representation they lacked in mainstream popular culture. A noble but heavy and unwanted burden which was scrutinised and raised the question of what it meant to be a “good Muslim” and whether Malik fell within the parameters. People wondered: are Arabic tattoos a contradiction? Should he be dating? Drinking?

On the other side, Malik’s open faith made him a prime target for Islamophobes — be it Bill Maher shrouding him in the guise of a terrorist, the fear-mongering far-right indicting him as a preacher out to mass-convert their children to Islam, or his receiving of death threats for tweeting support for Palestine (a reaction that was not meted to the array of non-Muslim celebrities attesting their support). The incessant harassment and cyberbullying endured by Malik for simply being Muslim is unparalleled among public figures and compelled him into silence on his Islamic faith. Perversely, however, there was a silver lining. These tragic events provided a springboard for Muslims to publicly discuss Islamophobia and raise awareness, recount their experiences of verbal harassment, physical attacks, and begin a narrative towards finding a solution to put an end to Islamophobic hate crimes.

This month, in an interview with British Vogue, Malik revealed he no longer identifies as Muslim. Although his younger Muslim fans, who in him found a mainstream representation of themselves, are sure to be left disappointed by this revelation, for most it will not pose a major shock. At the very least, it has been clear for some years that Malik is not a practising Muslim. It is interesting, however, that since being barraged by Islamophobic abuse in 2012, Malik has only felt comfortable to explicitly discuss his religious beliefs now that he no longer identifies as Muslim. This is a consequence of institutionalised Islamophobia, which insidiously obstructs Muslims, who vocally identify with Islam, from popular media. It coerces self-identifying Muslims into silence on matters of religion to avoid impeding their success.