In a post-Trump era, the voices of the silenced and dismissed are roaring back with a vengeance, particularly the female voices. According to Rutger’s Center for American Women and Politics, six women serve as governors in 2018. Of those women, four are registered Republicans and two are Democrats. The recent surgency of women breaking into the traditionally male-dominated political space forces more diverse experiences to come to the forefront and be considered in full.

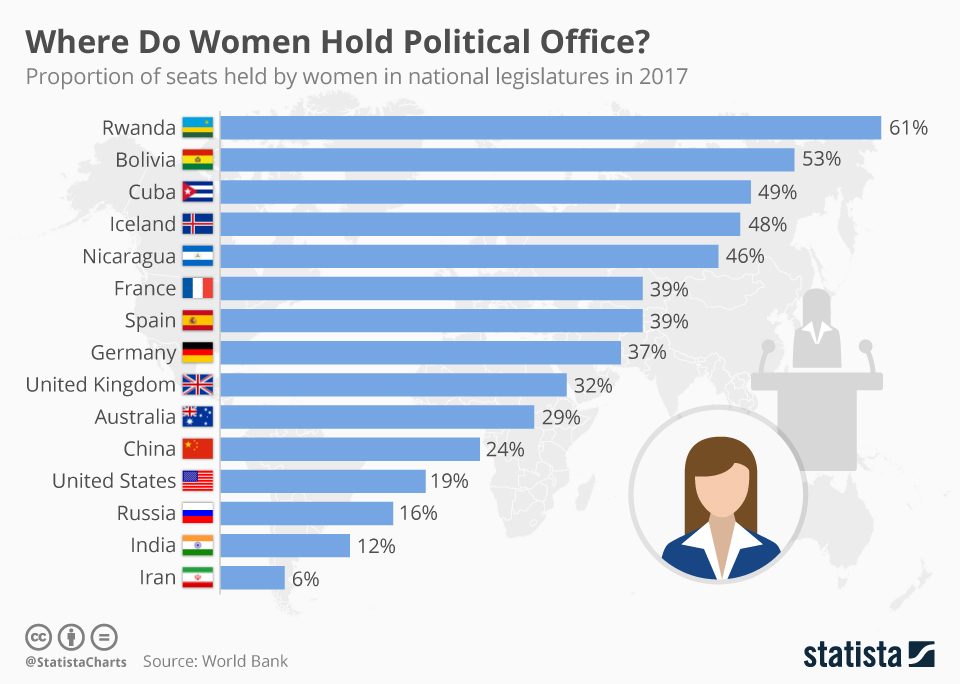

The impact of female voices and the political influence of women has become a pretty globally known fact around the world. In countries like Rwanda and Nicaragua, women holding office was more than 45 percent in 2017 alone. It’s no surprise that sexism has influenced the progression of women in political spaces. When we do earn these positions of power, we should also consider whether the voices of women that are included in these roles are inclusive and representative of all women. Based on the 2018 poll from Rutger’s Center for American Women and Politics, five out of six women represented in the poll were white women with the exception one being a Latina woman.

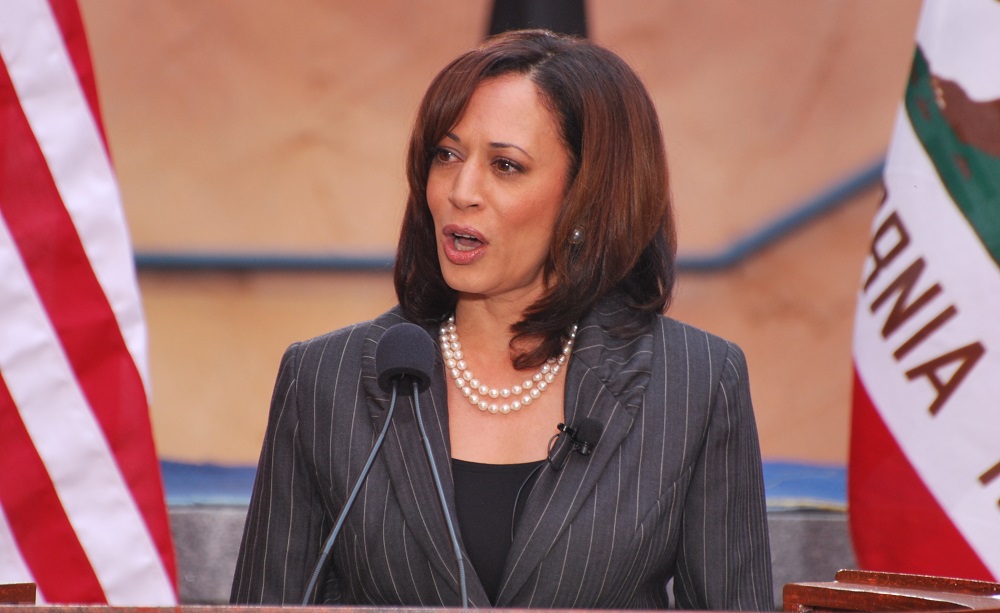

As we grapple with the overall concept of women’s lack of political representation, as a culture we should simultaneously wonder why South Asian women are underrepresented. Of course, there are notable exceptions such as Attorney General Kamala Harris (CA) and Nikki Haley (SC) but are these individuals representative of our distinct cultures, complexities, and diasporas? Beyond that, what is dissuading South Asian women from running for gubernatorial elections?

Though that question can stem from a series of different root issues and dynamics within the South Asian community, family dynamics and gender roles associated with those dynamics can shape the perception of who is considered powerful and who does not have the right to such power.

Most South Asian familial dynamics are aligned such that the father holds power over the family and is often the ‘final say’ in any major family decisions whereas mothers are there for the daily decisions and the everyday. With this dynamic as the norm, it speaks volumes to why South Asian girls, in particular, grow up to see these gender definitions as examples of how they should view power and who holds it. Even as young South Asian women, we were taught to not speak loudly and beat a man’s “beck and call” any time an uncle or man came to visit our houses. Additionally, we have pushed away from engaging in more “manly” activities such as sports and encouraged more to dance or play musical instruments. Growing up in that very gendered environment, why would South Asian women even consider politics as an option?

[Read Related: The Time is NOW: South Asian-American Youth Must Perform Their Civic Duty]

While this dynamic is not relevant in every South Asian family, it requires us all to deeply consider how we frame power and femininity. For too long, we have equated power and political interest with men and their capacity to see it forward. More recently, however, we have seen South Asian women rise stronger and smarter to the occasion through organizing and creating inclusive spaces for all communities to provide more fervent change to our political structures. The stereotypical, good desi girl is being repolished to fit a more realistic expectation of being a powerful, brilliant South Asian woman in a quickly evolving world where we are not raised to be an eligible bachelorette but an eligible representative of our community.