Sign up for @happyherfoundation‘s virtual book club to discuss ‘Well-Behaved Indian Women’ on Saturday, Sept. 26th at 11am PST/2pm EST (co-hosted by @mamajotes and @zabina_bhasin).

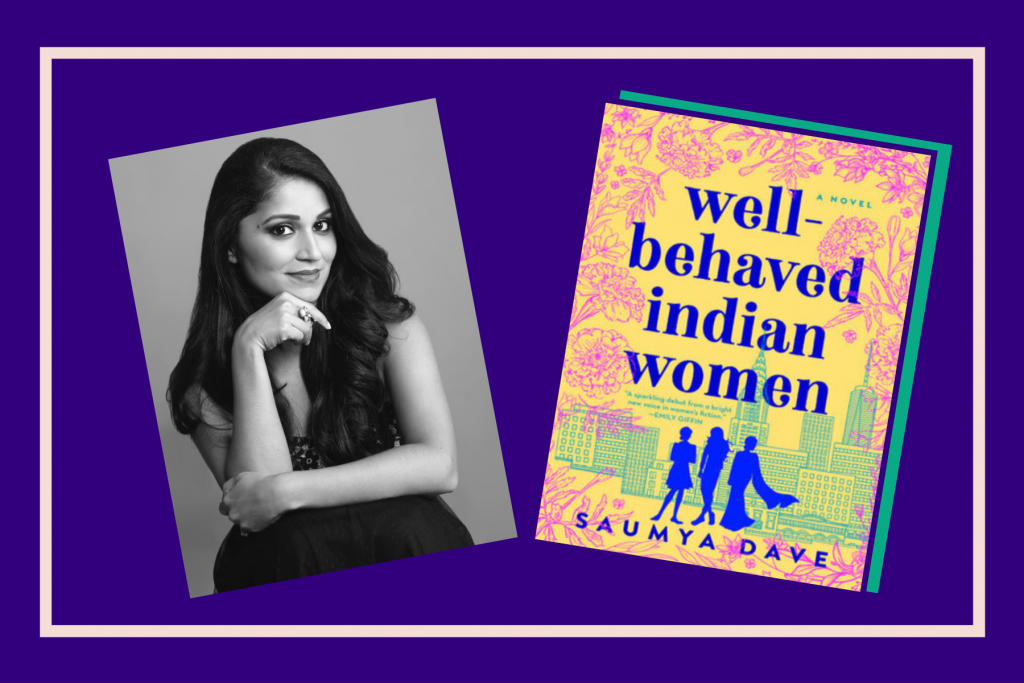

Saumya Dave‘s debut “Well-Behaved Indian Women” has been making waves in the publishing world and I was anxious to get my hands on a copy. When I began reading the novel, I was blown away by the multilayered storytelling and gripping plot lines.

We journey through time and geographic locations to follow Simran, her mom Nandini, and her grandmother Mimi. Simran comes from a family of medical doctors but finds her calling in psychology. She has it all: a kind, smart fiance, a prestigious graduate program, her own published book. However, she begins to question her seemingly picture-perfect life after a chance encounter with her writing hero.

On the outside, Nandini beautifully balances her personal and professional lives, but on the inside, she’s still struggling to find the happiness of her own. Years of compromise and self-sacrifice have left her worn out and feeling unfulfilled.

Mimi is the determined and witty matriarch of a family with multiple generations of intelligent and ambitious people. She has reached the highest levels of respect in Indian society, yet she feels as if she’s failed her family.

The multifaceted and even contradictory characteristics make these three women vivid, almost as if they are people we would encounter in real life. The story was especially relatable to me as I’m currently going through the process of applying to medical school while also balancing a grueling master’s program. I could see so much of my own life and family in this book. It was so refreshing to read about characters and situations that reflected my culture and immigrant upbringing.

After finishing “Well-Behaved Indian Women,” I wanted to learn more about the book’s development and the life of its author. So, I reached out to Dave to discuss her journey into writing and how she juggles her writing and medical careers. The culmination of our discussion is in the interview below.

*Quotes are edited for clarity*

[Read Related: Author Interview-Romance Writing and ‘Girl Gone Viral’ With Alisha Rai]

Tell us about yourself.

Hi! I’m Saumya Dave. I’m a writer, psychiatrist and new mom. I was born in Baroda, India and raised in Atlanta, Georgia. I recently finished my psychiatry residency at Mount Sinai Beth Israel Hospital in New York City. My debut novel, “Well-Behaved Indian Women,” was released on July 14th from Berkley/Penguin Random House.

When did you begin writing?

I always wanted to be a writer for many years, but didn’t believe it was actually possible. I was convinced I had to have a career that was considered more stable and also thought I could only have one job. But during my senior year of college, I realized how much I missed writing. I thought about what my future self would regret and the first thing that came to mind was writing a book. By then, I had struggled to find stories that represented the world I came from, and knew I had to try to write one myself. I went through twelve full rewrites and over one hundred rejections of the novel throughout medical school and residency.

Now, I’m an author and psychiatrist. I have a private practice and write when I’m not seeing patients. Both of my jobs are, at their cores, about understanding people. It took me years to learn that I can create my own path and that it’s okay to pursue more than one career.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CCzdyrQleL_/?igshid=1u7gpnh78uqhq

How do you balance being both a writer and a doctor?

It’s definitely been an adventure! This novel took me over 10 years from the completion of the first draft to the publication. In medical school, I wrote after my exams and usually spent weekends holed up in my apartment, in front of my laptop. During residency, I wrote during post-call and vacation days. The only way it worked for me was to tell myself I had two jobs and that when I wasn’t doing one job, it was time to do the other.

What is your advice for budding South Asian writers?

First, please keep writing! We need your stories more than ever. Also, if possible, try to create a network with other fellow writers. Writing can be a solitary journey and it really helps to have a place for mutual support and encouragement. Moreover, I wish my younger self knew that rejections are a part of the process. In total, I was rejected over one hundred times during my journey to get this book published. I was so used to the metrics of grades and evaluations because of school but writing showed me that feedback isn’t always that clear. It taught me to reevaluate my relationship with failure and seeing it as a learning opportunity, a place to grow from. Lastly, patience and persistence are imperative. Someone once told me to expect all creative projects to take much longer than I think they will. I had a romantic notion of having a book idea, writing it in my spare time, and seeing it on shelves within months.

[Read Related: Exploring the Highs & Lows of Medical School Through Poetry]

“Well-Behaved Indian Women” is so relatable to me as a Bengali-American because I’m going through the motions of applying to medical school while also trying to balance my personal life and writing career. There were so many little moments in the book that reflected my life and my family full of doctors. This begs the question, what inspired the creation of this story?

That is so wonderful to hear and your own journey resonates with me so much. I was always so inspired by the strong women around me, from my mother to my grandmother to my friends’ moms. They’ve demonstrated so much grit with everything they’ve done, whether that’s moving across the world to build a better life for their families, learning new languages, or caring for everyone around them. And I realized there were often mentions of the lives they left behind and the women they could have been if they didn’t feel the need to live up to certain standards. I really admired this mixture of strength, vulnerability, and resilience. I struggled to find stories showing these parts of their lives and knew I wanted to explore all of this through writing. The story of “Well-Behaved Indian Women” then started from three basic questions: What do we owe to ourselves and others? How much are all of us shaped by the roles we are placed in? How would my parents’ lives have been different if they stayed in India? All of these questions were in my mind during my clinical rotations in medical school, when I began experiencing some sexism and racism. When I tried to process those events, I often wondered what someone like Nandini would have done and what she must have experienced as a doctor training in an earlier generation.

It’s interesting to see how your protagonist’s story somewhat reflects and juxtaposes your own life story. She is an aspiring mental health professional and you’ve made a name for yourself as a psychiatrist. Was there a person or moment from your life that inspired her character?

I poured a lot of the confusion and fear I had in my early twenties into Simran. She truly is at a crossroads and feels this pressure to have everything figured out. In terms of the similarities between our careers, I’ve always been interested in mental health but initially wanted to be an OB/GYN when I went to medical school! It was only during the end of my third year that I realized my favorite part of each day was being able to talk to patients, learn their stories and see how I could have a positive impact, which is what psychiatry is all about.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CCEF1BYlS0X/?igshid=4j1ugf1mn41q

Tell us about your mental health advocacy.

thisisforHER is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit that provides mental health education through art therapy exercises. During a trip to Kampala, Uganda, my husband and I visited local nonprofits to learn more about their work. The heads of multiple different organizations asked us if we had any resources to help them incorporate mental health education into their existing initiatives. I was in residency at the time and after I struggled to find readily accessible materials to provide, I decided to design them myself. With the help of faculty members at my program, I created a curriculum that covered basic mental health education through group art exercises. One year after our initial visit, my husband and I went back to Kampala to pilot this with the organizations we had met with before. We were thrilled with the reception and hope to continue building more partnerships in the future. For anyone interested, there’s more information on the thisisforHER website. We are also on Instagram and Twitter.

Many times, South Asians feel pigeonholed into careers in medicine, engineering, or the sciences by desi immigrant diaspora culture and from our own families. “Well-Behaved Indian Women” touches on this a lot. How do we balance the desires of the people around us with our personal ambitions?

I appreciate this question so much and struggled with this for years. It can be so challenging to keep everyone happy and not want to let down the people we love. My parents were worried when I first started writing and often wondered why I was spending so much time on the book. I learned I had to to accept some level of disappoint in order to go after what I wanted. I also realized that my parents were coming from places of love and fear. They wanted to make sure I didn’t get hurt. It took some time, and there were many moments of doubt from both sides, but we are all now grateful that we were pushed out of our comfort zones. I appreciate my parents being open to learning about this new career path and way of life. The one thing that kept me going was knowing I was doing something truly for myself and I wanted to see it through. After a certain point, I became less concerned with whether I’d be published, and more with just wanting to pursue the work that sounded fulfilling to me.

My babies ???.

Samir surprised me with this onesie the week Sahil was born and we’ve been counting down until he could wear this. Shout out to @KristineESwartz for making sure the font is perfect! #wellbehavedindianwomen #wellbehavedindianbaby pic.twitter.com/7DQQFbesJR

— Saumya Dave (@SaumyaJDave) July 13, 2020

I loved how we have not just one but three protagonists in the book. Why did you want to make this an intergenerational story?

After Nandini’s storyline became clearer to me in medical school, I started thinking about roles, how often we put those we love into roles and how difficult it can be for us to see them outside of those. I thought an intergenerational story would be the perfect landscape to explore the idea of roles. I found old pictures of my own mother and wondered about who she is to her family of origin and how that’s different from who she is as a mother and wife. In “Well-Behaved Indian Women,” I wanted to show how Simran, Nandini, and Mimi straddle the blurry line between mother, daughter and friend, and how those relationships are such fertile ground for misunderstandings, love and connection. The most touching thing I’ve heard from readers is when they’ve told me the book inspired them to ask their parents about their former lives.

From the outside, Nandini is the perfect Indian wife. She’s educated, professional, balanced, caring and consistent. But when I would read the chapters that were narrated by her, I almost got the sense that she felt broken on the inside. What did you want to convey through her narrative?

There is such a divide with Nandini between what others see and what she’s really feeling on the inside. She feels so much pressure to show she’s accomplished everything that’s been expected of her. I wondered what would happen to a woman like Nandini if her regrets caught up to her, if she realized she didn’t fulfill the amazing potential she had in her career. A lot of her conflict comes from wanting to balance these opposing forces that have shaped her. But despite everything she’s gone through, she sustains this hope in herself, even when she doesn’t realize it. I wanted to show what it would be like if she finally went after the things she always wanted and stopped caring about what others thought.

[Read Related: Meet Lakshmi Devy-A South Asian-American who Chose to Pursue her Inner Movie Star Over her Career in Medicine]

Overall, what is the message that you would like our readers to take away from “Well-Behaved Indian Women?”

I hope readers find some solace and self-acceptance. I’m so grateful for the books I read growing up because of how they made me feel as though I both mattered and belonged. My wish for anyone reading “Well-Behaved Indian Women” is that they feel less alone and hopefully, more understood.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CBwJ2P_lEY7/?igshid=1j9s1ozywfqgc

Get your copy of “Well-Behaved Indian Women” from Barnes & Noble or Books A Million and keep up with Saumya Dave through her Twitter and Instagram.