by Sundeep Hans

My parents were ecstatic when I was born… or so I’m told. By virtue of being the first child, I was special — but there was no celebration of my arrival. They were happy, but nobody was in full Punjabi celebration mode. There was no party, no drinks (well, maybe a few uncles had a peg or two), and no ladoo!

Here I was, this bundle of joy — the first of what would ultimately be four children — and nobody thought to deliver some ladoos to celebrate? I made them both parents, for crying out loud! My sister was born a year later — definitely no celebration — so there was a pattern.

In many South Asian cultures, particularly in North India, the family of a newborn delivers ladoos (traditional South Asian sweets made of flour and sugar) to all their friends and family. Traditionally, however, only male births have been celebrated in this way. If you have a baby girl, at best you might expect a lukewarm “congratulations” followed by almost feverish reassurances that the “next time it will be a boy, you’ll see,” and at worst you might be besieged by people who could be mistaken for mourners, sadly “tsk tsking” at your fate.

When my brother was born a few years later, the celebration was epic! There were parties, champagne, whiskey, and ladoos. Tons and tons of ladoos. Ditto, ten years later when my second brother joined the party. I remember that because my grandma made them in huge batches at our house. Seeing box after box packed lovingly for delivery, my sister and I asked how many boxes they had filled when we were born. I remember feeling outraged when we were told that no ladoos were delivered at all because “we only do it for the boys.”

We were little kids, but even still, we understood the unfairness of this tradition. Both my sister and I issued our joint indignation at the unjust treatment we were given at our birth. We didn’t let up, either. We kept asking ‘why’ every chance we got, but there was never a good enough answer. It didn’t make sense to us, especially since in our religion, Sikhism, the belief in universal equality is one of the most important principles of the faith. In fact, gender equality is enshrined in the Guru Granth Sahib Ji (our holy scripture).

[Read More: The Brown Girl Template: How to Make the ‘Perfect Brown Girl’]

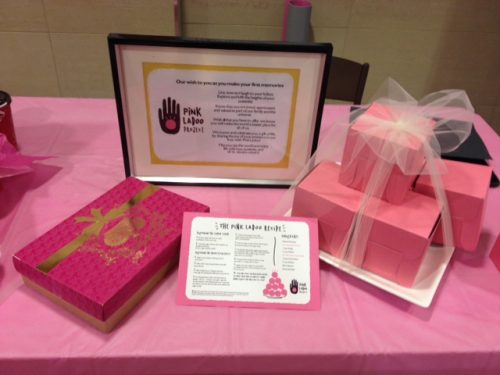

But the much-talked about, global initiative Pink Ladoo Project aims to break the gender biased custom prevalent in the South Asian community. It is celebrated on Oct. 11 every year to coincide with the International Day of the Girl Child. Through the delivery of pink ladoos (as opposed to their usual yellow color) to all families of newborns, both boys and girls, the goal is to plant the seeds of change in the community, literally “one ladoo at a time.”

This year, the project had its Toronto launch at two hospitals in the Greater Toronto Area — Brampton Civic Hospital and Etobicoke General Hospital. These two hospitals are a part of William Osler Health System (Osler) and serve a diverse population, which includes a large South Asian community. As the community and clinical partnerships lead for Osler, I had the pleasure of liaising and coordinating with team Pink Ladoo Toronto.

The army of volunteers, both women and men, were decked out in beautiful pink shirts were at both sites. For the whole week, they supplied our staff, physicians, patients, and families with a steady supply of delicious pink ladoos. People came out in droves and hung messages in support of gender equality on the ‘support trees.’ The week-long awareness campaign culminated on Sunday, Oct. 16, with volunteers visiting the women and children’s units at both sites and delivering pink ladoos to all of the families of newborns. It was a tremendous success, and it was profiled in the local news agencies, both print and monline. It gained a lot of traction on social media as well.

[Read More: Prime Minister Trudeau’s Thoughts on Feminism Will Make You Want to Move to Canada]

The conversation about gender equality that the Pink Ladoo Project started is proof that culture isn’t this static thing. We don’t have to rigidly hold on to something because “it’s always been this way.” We can change it. By asking why we can challenge these unjust customs because nobody can reasonably justify injustice.

I’ve seen this at work in my own family. The relentless barrage paid off because fast forward to about two years ago when my sister had a baby girl (my parent’s first grandchild), my parents were the ones asking “when will we do the ladoos” and “how many ladoos should we order?” We all celebrated this new life entering the world — and everyone celebrated with us! If the unfairness of a cultural practice is so blatantly obvious, it’s time for some self-reflection.

Learn more about the Pink Ladoo campaign at pinkladoo.org.

Sundeep Hans was born in Toronto, raised in Brampton, with a slight detour via Punjab. She has a great job, where her work involves collaborating with clinical and community leaders on initiatives around diversity, equity and inclusion in the region to reduce barriers for health care access in vulnerable populations. She has a Master’s degree in Global Diplomacy from the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, a Bachelor’s degree in History from the University of Southern California, and is almost finished with her post-graduated certificate in Ethics. She loves to read, travel and talk to anyone every chance she gets. You can follow her on her blog and on LinkedIn.