It’s not every day that a film leaves you feeling completely overwhelmed with a flood of mixed emotions — from grief and hopelessness to fear and rage, all the while brimming with a sense of pride for the protagonist. This usually is a testament to the maker’s cinematic prowess; their ability to not just engage their audience but also invoke a response. In “To Kill A Tiger” however, this is a result of both the director’s unrestrained and incisive approach and the eye-opening reality that unfolds on screen. Emmy-nominated filmmaker Nisha Pahuja’s documentary, “To Kill A Tiger,” is not at all gritty or violent in its depiction; there is no blood and gore that compels you to feel the pain and empathize. It’s the trauma, collective suffering, and the almost sickening reactions that surround the struggle that makes it an eerie watch.

[Read Related: ‘Devi’ Review: a Short Film That Says Volumes About Rape Culture in India]

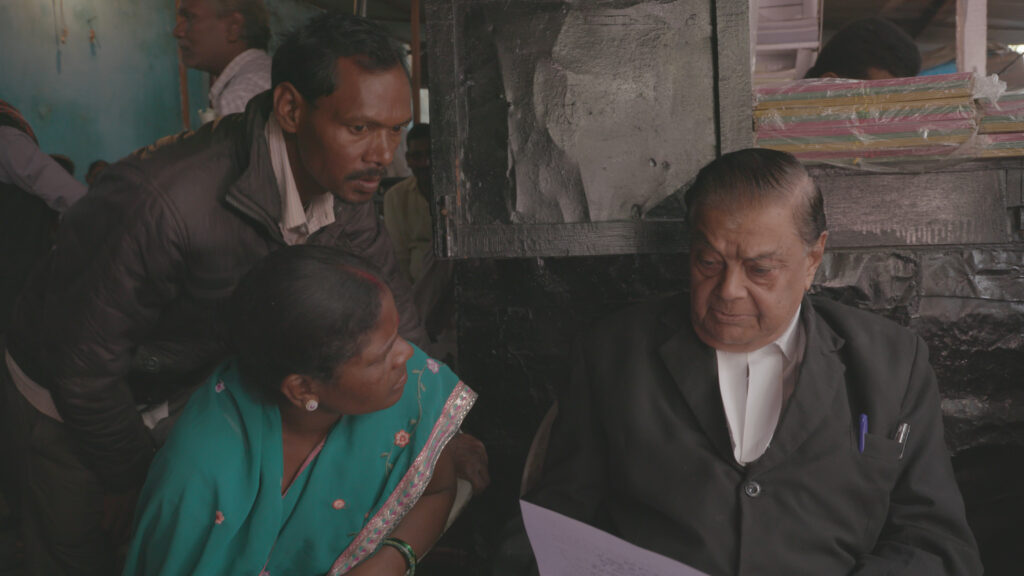

In essence, “To Kill A Tiger” is an unfiltered look into the aftermath of a horrific sexual assault in Bero, a tribal village in Jharkhand, India. The film starts off with Ranjit, a poor rice farmer and 13-year-old victim Kiran’s father, recalling the details of her brutal rape, at a family wedding, by three men including her cousin. After Ranjit files the case, the perpetrators are arrested immediately, but the road to justice is long and dreary, and the chances of getting it, woefully small.

In India, where a woman is raped every 20 minutes and where 90% of those rape crimes go unreported, Ranjit’s unwavering support for her daughter and her right to justice is a rare sight. He is joined by a host of activists including those from Srijan Foundation to further his cause, in the hopes that his unlikely win may bring some form of systemic and societal change. But in his almost 14-month-long, arduous journey, Ranjit and his family find themselves stuck in a destructive cycle of victim-blaming and the intense pressures of upholding the community’s so-called honor. Comments like “she should have known better,” or “she must’ve been a tease for boys will be boys,” and suggestions of marrying her off with one of her rapists so as to keep the village united and let peace prevail, are a harrowing reminder of how much of rural India is still so deeply entrenched in patriarchy and powered by toxic masculinity, which is what actually led Pahuja to this case in the first place.

Back in 2014, Pahuja started laying the groundwork for what eventually became “To Kill A Tiger” in the edit room. At the time, she had set out to explore Indian masculinity and “what creates these ideas that men, and the Indian culture specifically, need to dominate and oppress women.”

“After the Delhi gang rape. I decided I wanted to make a film on Indian masculinity. I spent a fair bit of time researching and raising funds for the early development phase because it’s such an abstract concept; how do you tell a story about masculinity?” Pahuja shared, while chatting with Brown Girl Magazine.

“Over the course of my research, I came across the work of a Delhi-based organization, Center for Health and Social Justice. They, essentially, are pioneers in the space around masculinity. They understood very early on that if there were any substantial, effective strides to be made to end the discrimination that exists against women, one would actually have to tackle masculinity, and give men a new way to be male. The film that I initially set out to make was following their work. They were running a program in the state of Jharkhand and Ranjit was enrolled in that program. And that’s how I came across this story. It wasn’t like I was looking for a story about a sexual assault. The incident just happened around that time.”

But shifting the focus to a deeply personal story with an uncertain future, and one that was highly sensitive to its surrounding environment (significantly volatile in nature), posed a series of challenges for both the family involved and the crew. For one, it was crucial to ensure that the fact that there’s a camera present does not, in any way, influence Ranjit’s course of action; and that both Ranjit and Kiran have room and the freedom to make decisions as they see fit.

“We always made it very clear that they shouldn’t do what they were doing for the camera, or for the videos. We told them we will support whatever decision they want to make and that they shouldn’t feel a compulsion to keep pursuing this. We wanted to ensure that they were pursuing justice, in spite of all the things that were going on. Because we were all worried for them. We didn’t want them to be in any kind of danger or to be in a position where they were unsafe,” Pahuja stressed.

As is evident in the film, there are plenty of moments when it seems Ranjit would jump the ship. Apart from the mental and financial burden of keeping up with innumerable court dates, and a system that does little to help the marginalized get justice, the threats to his family’s wellbeing were insurmountable. In one instance, we see this growing hostility veer towards Pahuja’s crew — the villagers question the filmmaker’s continued interest in the incident, warning her to stop meddling in their community’s affairs. Pahuja recalls the instance:

“It was a scary situation. We were aware that this eruption might happen; it wasn’t unexpected but when it happened, it was a shock. You know what I mean? We had been in that village for several months filming, trying to get people on our side, trying to create relationships, even with the boys’ families. And Ranjit was fine with that; he understood why we needed to do that. We made a lot of effort to not be a bull in a china shop; we were very careful. We were certainly aware of the sensitivity and of the possibility that there could be conflict, but not to the degree that [it] happened. I was shocked, I was afraid but the primary emotion that I had was also one of guilt. I felt very ashamed of myself for disrupting something very complicated.”

In the face of such adversity, with the world shunning her and with every possible witness jeopardizing her shot at justice, it is Kiran’s unblemished view of the world, her relentless faith in good winning over evil, and her fierce determination to see her attackers pay for their crime, even at such a tender age, that’s truly admirable. As a viewer, you’ll find yourself at your wit’s end watching Kiran constantly relive her trauma, repeating meticulous details of the incident to one legal official after the other, but she perseveres, also lending her father the courage and the strength to continue her fight.

[Read Related: Jia Wertz Advocates for Criminal Justice Reform With her Documentary ‘Conviction’]

Is “To Kill A Tiger” a depressing exposition of the inherently patriarchal, and significantly problematic, mindset of the Indian population that is in turn breeding rape culture? Yes. Does it leave you incredibly frustrated and disappointed over the bare minimum impact that Ranjit and Kiran’s defiance and eventual victory has over prevalent attitudes? Yes. With a plethora of rape cases in India suffering a fate worse than Kiran’s, was it a story that needed to be told? Definitely yes. Though a world where women’s voices are not silenced may still very much feel like a utopian fantasy, “To Kill A Tiger” is effectively opening a dialogue by laying bare the roots of it all. Through this profoundly resonant story, Pahuja is helping us understand why whilst taking the first step towards the ‘how’ for her work, and the scope of impact, doesn’t end with the audiences.

“Right now, we’re working with Equality Now; they’ve come on board as our impact partners. And we’re devising a kind of global strategy in terms of what are the things that the film can achieve? And the change that we’re seeking is both at the legal level and at a systems level. And of course, at a cultural level as well. For change to happen, you have to change culture, and culture comprises many different layers. So you have to have an approach that looks at all of these different layers. We have some very specific things that we know we want to do such as creating a fund for survivors. We also want to create a coalition of survivors in India. And then, of course, we want to work on masculinity. We’re really hoping that with Ranjit being the role model, the film can travel with [the] organization to have an impact on men and boys.”

“To Kill A Tiger” is currently showing in cinemas across the US.