The shortest way to teleport inside someone’s head is by editing their writing. I realized this was true in January of 9th grade when my mom peered at my laptop on the living room couch.

“Dikka*,” she asked me, carefully, “How should I tell your teacher that I am concerned about your grade?”

For most Indian-American children, what she just asked me would have been the sentence that begins all nightmares. But I was safe, for two reasons: 1) the crisp 89 that I had gotten on my English midterm would only merit partial death and 2) the word “how” meant she had no clue how to start. So what was the problem? I had no clue either.

Even as a grammar purist with perfect scores on the English and Reading sections of the ACT, I could not escape the enigma of a run-on sentence or a misplaced apostrophe. Like most teenagers, I had downloaded Grammarly to write my emails for me and was more versed in the art of a really funny text to my crush (that would then be left on read) than the email.

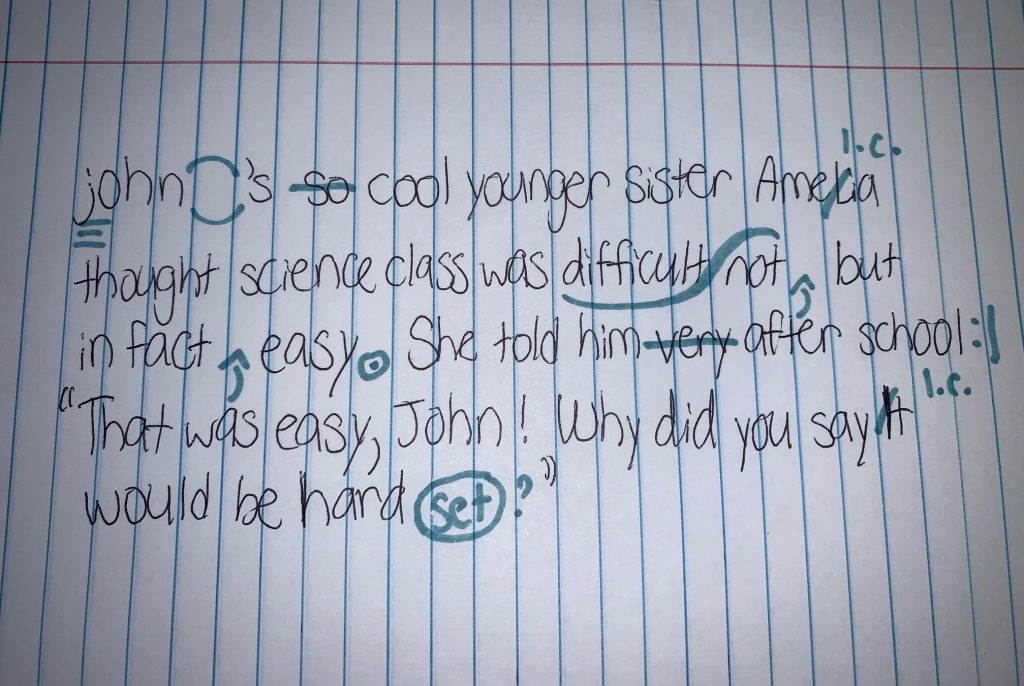

Determined to help my mom, I scoured the internet for tips and tutorials on how to write. Next, I made informal lesson plans for her. We started with “To whom it may concern,” moved on to “Please let me know if you have any questions,” covered the difference a colon or a comma could make, and even advanced to how active vs. passive language can completely change the tone of an email. We’d read it once, twice, eight more times until we’d spotted every incorrectly-placed apostrophe and object pronoun.

Her paranoia was my paranoia, and to us, our paranoia was part of the process, something we needed to overcome to push out a final product. It wasn’t until I edited my mom’s emails that I realized why she was so euphoric when we finally pressed SEND.

[Read Related: Living as a First-Generation Indian Immigrant Who Can’t Speak Her Native Language]

To err is human. But if you’re a woman of color, erring is inconceivable. Women of color can’t afford to make any errors, not just grammatical ones, because the room for error is so small. I’m lucky to grow up in a family that made me feel empowered as I am, but the pressures of grammar still persist: that the people I write to will never take me seriously because of how I write. These pressures are inescapable to those of us who are the only young woman of color in writers’ conferences or board meetings or speaking events, and the persuasion of perfectionism for someone like me (who has been all of those things) is too great to resist.

Grammar is a tool of structural violence that has historically weaponized articulation as a form of institutional power, from slave literacy tests to recent scoring guidelines for the English portion of the U.S. Naturalization Test, marginalizing the intellectualism of women of color in the process.

As a female minority student who has dedicated years to perfecting it, I think there are undoubtedly some things you have to be a woman of color in order to understand. The screaming in supermarkets to speak English, the terror that one misplaced apostrophe or one “who” instead of “whom” labels you as uneducated or incompetent or a diversity hire, the way our names on Word documents forever register as red-squiggle incorrect spellings of something else rather than just existing as what they are. Even within our demographic, women of color are constantly expected to perfect upon their English, and ourselves, in order to fit Eurocentric standards of professionalism. And though we Anglicize our identities to squeeze onto Starbucks cups and restaurant reservations, it is never enough.

I’m not alone, either. Millions of women of color seem to grapple with grammar every day, both in their home countries and America. In her first job as a manager in the United States, my mom watched non-minority women on staff with half her incredible work ethic suddenly double in leadership positions. She even made sure to ingrain in me the impossibility of failure, leading to perfect standardized test scores and glowing parent-teacher conferences at predominantly white schools where teachers meant, “She’s very articulate!” as a compliment, in the way that the other kids in the grade never usually have to be. We have to work twice as hard to stand out in the corporate world, and while our hypervigilance and perfectionism are valued, our articulation of English is often shamed for being unprofessional.

But in researching the art of the email, I observed that women of color are working around that by revolutionizing the rules of language in ways that previously were not available to them. Best Selling poet Rupi Kaur (of Milk & Honey and The Sun and Her Flowers) adjusted perceptions of unconventional lowercase grammar from being unprofessional to being expressive. In a statement on her website, Kaur explains that she did this to pay homage to the Gurmukhi script of her mother tongue, Punjabi, where all letters are the same, but also to represent the equality she wants to see more of within the world. Instead of reacting explosively, the Internet adapted to her massive mainstream success. Kaur may not have been fully responsible for the perception of ingenuity and informality associated with increasing lowercase use, but poets and other creatives today can certainly be seen experimenting with different spaces, shapes, drawings, and upper/lower/toggle cases of writing in conjunction with seeking to express themselves in more honest ways.

[Read Related: Living as a First-Generation Indian Immigrant Who Can’t Speak Her Native Language]

While Kaur has revolutionized the written word, other young women are revolutionizing the spoken word. Young women, often mocked for overusing modifiers, quotative ‘like’ and slang, are at the front of language progression. “Young women [dominate] those linguistic changes that periodically sweep through the media’s trend sections, from uptalk to ‘selfie’ to the quotative like to vocal fry,” says an article by The Quartz. “[They are changing] the distinctive /r/ pronunciation of New York City…the /aw/ pronunciation in Toronto and Vancouver, the ‘ch’ pronunciation in Panama…/t/ and /d/ pronunciations in Cairo Arabic, vowel pronunciation in Paris, entire language shifts like that from Hungarian to German in Austria.”

Inspired by some of these incredible women, I created a checklist for how and when to correct English-language grammar, by keeping in mind the following.

First, access to resources impacts good grammar. There’s nothing wrong with speaking or writing in a way that everyone can understand, as standard grammar makes sentences clearer. But not everyone has access to the same tutoring, college education, or grammar-checking software programs, and standardized rules of grammar only advantage those who have had the opportunities to learn them. This means that writers without formal education are disproportionately impacted when pitching their writing to and building connections within a predominantly white publishing industry.

Additionally, the intention is everything. There’s nothing wrong with the intention of correcting someone else’s grammar to better their speech. We native speakers shouldn’t feel ashamed that we know or use correct grammar, but we really should question if we find ourselves wielding it as a benchmark of superiority rather than a bookmark for someone else’s next chapter of learning.

Third, context matters. If you have a job that requires you to correct others’ grammar (editors, librarians, language teachers, English tutors), or if people ask you to correct their grammar, offering a correction is acceptable. But if no one is asking you to correct their grammar but you’re doing it with the purest intention to help, ask yourself: is now the right time? Is what they’re saying more important than the way they’re saying it, and will your correction only amplify that? Do you have difficulties understanding them without using perfect grammar? If you answered YES to all of the above questions, there are several polite and respectful ways to correct their grammar, like modeling what you meant by asking the person in question what they said using the correct sentence.

Lastly, effective communication is about understanding. If you write well but have awful grammar, your writing is able to effectively communicate meaning. Yet if you have good grammar without good writing, your writing is meaningless. And that is arguably the worst thing a writer can do: breathe life into sentences that make people feel…nothing. The words I tell my mom every day—I love you. I am here. I had a dream. I made it happen—would be so much weaker if I said them in their most grammatically correct forms. They would be just words, and words, no matter how perfect, do not give each other meaning. People give words meaning.

In teaching my mom how to write, I searched the internet to become a better writer. But I also searched inside myself to become a better person, because I remember a teacher criticizing a foreign exchange student’s English while complimenting mine, and even earlier, being at a friend’s house when her immigrant mother commented on how I spoke in a more sophisticated way than her daughter. So I’ve also been a part of the system to uphold this impossible standard of grammar perfectionism for other minority women.

I’m still unlearning shame from this. I’m allowing myself to document the narratives of the historically disenfranchised until my fingers hurt, to tell stories of the generational struggle until my throat is sore, to embrace writing everything completely by myself instead of running away from the cultural and grammatical nonconformism my work embodies.

And I’m still figuring out how to teach my mother how to write an email.

There is no remedial solution for this intergenerational struggle which defines countless socioeconomic lives: no spell-check which can substitute the importance of grammar in our lives, no thesaurus search that can suggest alternative explanations for how the articulation of English impacts both confidence and career trajectories of so many bright women of color. In fact, this problem of modern communication exceeding proper English grammar continues to increase as Americans conduct more and more business deals with women and ethnic minorities who articulate differently to them.

But even dissecting a societal problem as small as my email anxieties reflects a dichotomy in our society: about how one chooses to speak, and how one chooses to listen. Through their unique capability to revolutionize grammar, women of color have the revolutionary power of leading and healing this divide.

[Read Related: Bijoy Dibosh: The Birth of Bangladesh, its Mother Language, and My Mother]

I want to support the interest in language held by young women of color by equipping them with school supplies and a positive mindset to succeed inside and outside of the classroom. I want to teach more young girls to take risks in a conversation–whether using a dependent clause as a standalone sentence to pitch a new software program, or using modifiers while articulating to their boss why they should be paid the same wage as their male colleagues–so that they can take more risks in life. They are sure to build more relationships that empower and equip them to succeed, and we are sure to benefit from them. I love grammar, and I think there’s something inherently revolutionary about the malleability of grammar, in our infinite possibilities to explore solutions wherein grammar conforms to our everyday dialogue rather than us always conforming to it.

So far, I know two languages. I am practically illiterate in one and a published author in the other. As it happens, I never had a tutor, or a writing coach, or a copy editor in either of those languages, so there is an intercontinental volume of awkward phrasing and untranslatable jokes bridging them.

But I want to empower other people with my duality, not in spite of it. I want to inspire hope with my words so that girls like me will see in themselves the power to create. English may always be the language that houses my tongue, but every day I get to choose how to make it my home.

Some may ask, “What happens if we mess up?” Maybe we should swap that ‘if’ for a ‘when’. Because it’s not about if we mess up, but when we mess up—and we will. It’s about correcting our mistakes and learning from them, while also being forgiving of ourselves and others. Maybe young women of color like me can’t afford to fail right now. But when we do, there should be more space than the laptop space bar for forgiveness. And that’s on the most important grammatical tool of the English language: period.

*Dikka = sweetheart