by Antara Mason

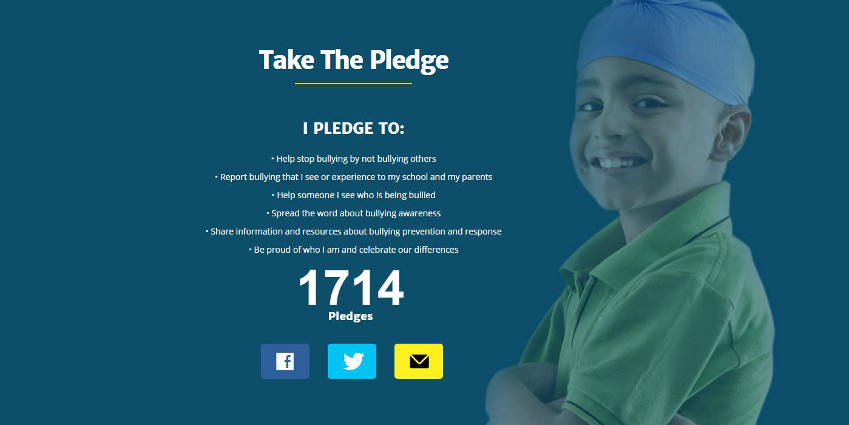

The following piece is a part of the “Act to Change” initiative, a public awareness campaign working to address bullying, specifically in the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community. The campaign website, ActToChange.org, and its social media tag #ActToChange provide AAPI youth and community members with platforms to share their stories, engage in dialogue around bullying awareness and prevention, and “Take the Pledge” to join the #ActToChange movement.

As a proud partner of AAPI’s anti-bullying campaign, we pledge to publish stories written by Brown Girl contributors on their experiences with bullying. In addition, we will host a Twitter chat in the coming weeks to empower young adults and their families with the knowledge and tools they need to help stop and prevent bullying in our communities.

My first encounter with bullying struck me when I was four years old. We lived in Sandpoint, Idaho. (Yes, that Sandpoint, the headquarters of a white supremacist group. Don’t ask me what my white parents with two brown Indians were doing there, because I honestly don’t know. Being adopted is tricky.)

Every morning I was dropped off at Miss Danielle’s daycare and I headed straight towards the playhouse in the backyard. Except the day that Spencer came to town.

I don’t know who Spencer was. I don’t know what kind of parents he had or his background. But I do distinctly remember being hit in the chest with a toy plastic orange. “Get out!” He had yelled and laughed as he tossed a banana at me. “Go away! You can’t come in unless you are not brown!” Confused, I went away crying. Of course, my daycare teacher raged at Spencer’s parents. But even now, I look at how young I was when the bullying started and I shudder.

What causes that kind of behavior in such small children?

From kindergarten to sixth grade, I was maliciously targeted for being proud of my race and various other personality traits. I was self-conscious about my infant abandonment, so I became clingy with the few friends I made each year. None of them ever stayed more than a year, so my mother and I began to refer to the reoccurring problem as my “friendship problems.”

[Read Related: One Sikh Girl’s Struggle of Becoming Accepted as an American]

During the sixth grade, I began to take Bharatanatyam dance classes and learn Hindi. My parents were so supportive! My friends—not so much. I couldn’t breathe when I found out that they had made a video depicting me hanging myself.

How cruel they were!

How often they told me to just be a normal girl, and stop talking about my homeland. I burst into tears and that night cried myself to sleep in my mother’s arms.

When I moved to Montana a year later, I was never aggressively bullied again as far as I can remember. But I wasn’t accepted by my classmates as an Indian girl, nor was I accepted by the Indian community. I wasn’t authentic enough. I was raised white, so that was all I was. I tried to introduce my family to the Punjabi family in town, but they wanted little to do with me after they saw my German mother and father.

As an outcast, I wandered the halls, and never had a solid set of friends. My identity has always been a force to reckon with and I still today am passively ostracized for the paradox it creates.

You see, being bullied isn’t always a physical action in society.

It’s sometimes just a quiet feeling projected onto you that you just don’t belong. Talk shows promote quiet bullying more than anything. How many times do we witness adults picking on other public figures for their clothes, ideas, body shape, and so much more?

I firmly believe that if part of our culture diminishes, the bullying will subside. Nothing can say, “This is a great idea,” more than a stand full of people laughing and clapping as Tyra Banks rips apart some poor girl’s posture on a reality show. Nothing promotes race separation like TV shows that portray races as being fundamentally different in every way. These quiet, subconscious messages from our media reinforce the idea that we must conform our identities to the correct category or face passive bullying, and loneliness until we do.

[Read Related: One Brown Girl’s Struggle to Keep her Indian-American Identity]

Today, I look back at my experiences of being bullied and I now realize how strong they have made me. I was forced to put my identity through hell and high water, which clarified what I valued in both of my cultures.

Now, I pride myself in being confident enough to be both an Indian girl and a daughter of two white parents. However, I will stand against bullying because no matter how much good bullying may have done me as a mishap by-product, no child should ever, ever have to cry themselves to sleep at night.

Antara Maso n is a freshman at Boise State studying secondary education. She enjoys pondering odd and unique thoughts in-between her favorite job being a barista. She’s a “SuperWhoLock” to the death and loves her friends even more! The sooner she can get out into the world and start changing things for good, the better! Tally Ho!

n is a freshman at Boise State studying secondary education. She enjoys pondering odd and unique thoughts in-between her favorite job being a barista. She’s a “SuperWhoLock” to the death and loves her friends even more! The sooner she can get out into the world and start changing things for good, the better! Tally Ho!