Prakash Churaman’s journey from the carceral system to freedom lasted seven years, five months and 28 days. On December 9, 2014, he was a 15-year-old boy who’d been through too much – abuse from a parent, school suspension, juvenile detention and living in a group home. He was arrested that night after his friend, Tarquane Clark, was killed in a robbery gone wrong. NYPD detectives interrogated Churaman and coerced him into a false confession.

NYPD officers brought him into custody because Clark’s grandmother thought she heard Churaman’s voice saying “mama, me not kill you,” and alleged that he pointed a gun at her head.

Though there was no physical evidence tying him to the crime scene, Churaman faced a state jail, Rikers Island and home confinement for six criminal charges.

[Read Related: Op-ed: I’m Tired of Brown Women Being Raped, Beaten and Killed]

He maintained innocence, refusing to take plea deals throughout his trials.

In prison, Churaman says, “I woke up everyday telling myself ‘I’m not gonna stay in here and just admit guilt to a crime that I know I did not commit, just to appease a system that relies on conviction rate.’”

View this post on Instagram

Years later, under pressure from community and district leaders, the Queens County District Attorney, Melinda Katz, dropped all charges against Churaman on June 6, 2022.

Churaman, now 23, has told his story several times; detectives Daniel Gallagher and Barry Brown fed him false information to make him confess that he was present at the robbery and dug into his childhood traumas, using his mother’s presence to compel him to finish the session quickly. After three hours of interrogation, 15-year-old Churaman, who had a learning disability and mental health conditions, told Detectives what he thought they wanted to hear—he was at the scene though never had a weapon or any part in the murder.

Yet, under New York’s felony murder rules, if a person commits a felony and someone gets murdered on the scene, that alleged felon can be charged with murder as well, even if they had no part in it. So when he went to trial in 2018, the jury found him guilty of six charges — the highest, second-degree murder.

Thinking about his experience with the criminal justice system, he says, “I get really angry, really, pissed because I know that they’re doing this to hundreds to thousands of innocent black and brown teenagers just in this city and state.”

Churaman spent four years on Rikers Island, New York City’s largest, most horrendous jail while awaiting trial because presiding Judge Kenneth Holder denied him bail.

“All I can say about that place is that it’s a catastrophic disaster,” Churaman says, straining to find the words. “They got to shut that place down. It’s just pure wickedness and evilness that is on that island.”

New York City officials have long faced backlash over Rikers Island and the inhumane conditions inmates face. In 2021, 16 inmates in the Department of Corrections custody died, and in August 2022, the DOC reported the 12th death of an inmate for the year. In fact, as of August 2022, 85.57% of detainees in NYC jails are awaiting trial, not convicted of a crime.

Churaman met countless others who maintained innocence or were awaiting trial.

How this is possible?

In an interview, Churaman’s attorney, Jose Nieves, says, “in every interrogation that they [NYPD officers] do, there’s going to be a level of deception, manipulation and coercion,” he says.

Once a suspect has their Miranda Rights read to them, they have few protections if they waive their right to remain silent. If the waiver is found invalid, either from coercion or inability to waive, the courts can’t consider the statements. But statements made through coercion by officers are often not picked up by the courts.

“I would say in every case that a juvenile is in a situation of being interrogated by the police and they don’t have a lawyer present, it’s going to be highly likely that a certain level of manipulation and coercion and deception will be used,” says Nieves.

According to Nieves, introducing a learning disability or a mental health issue makes a person even more vulnerable.

Churaman’s mother was present during his interrogation but did not understand the Miranda Rights. Neither did Churaman, who only wanted to go home.

Every factor worked against Churaman — he was 15, had learning disabilities and psychiatric conditions, was gravely uninformed and previously incarcerated.

When Churaman was 14, NYPD officers arrested him for criminal possession of a weapon. They were answering a call from his mother, who worried that her son may have taken her cellphone when they found a gravity knife in his dresser.

“I already had a rough upbringing here in Queens,” he says, detailing previous experience in a group home and a desire to protect himself.

Despite being unaware of the consequences of owning a knife, he was sent to a secure juvenile detention center in Brooklyn.

Several months later, he was arrested again for the murder of Tarquane Clark.

He describes the aftermath as “waking up everyday in a living nightmare.”

Grieving for his friend was impossible when incarceration was tangled with it.

Churaman had few resources while incarcerated — he told the Asian American Writer’s Workshop about a close friend he made in prison, the Muslim inmates at the “masjid” and later, the law library.

Motivated by, in his words, “years of unjust incarceration,” he taught himself about case law, subpoena laws, and criminal procedure law. He began to understand his experiences he says, and how “cruel and immoral the system is,” says Churaman. To him the system is flawed. He describes it as conducting “wrongful prosecuting” and lying to people by “promising us these rights.” “They just manipulate and coerce and use deception in any way they can. That should not be the laws of the land; that should not be how society is regulated,” he says.

Now free and empowered by supporters through his grassroots organization the Free Prakash Alliance (now called Prakash Churaman Free), Churaman plans to sue the city for $25 million for false imprisonment, malicious prosecution, denial of a fair trial, false arrest and other related claims.

“It’s the only right thing left that they can do,” he says, “after all the torture that they forced me through.” But, knowing that the money would be coming from taxpayers, not those involved, leaves him wanting.

Despite his exoneration, because the Queens DA’s office dropped the charges on a technicality of an “infancy defense” motion filed by Churaman’s team, officials continue to defame the 23-year-old. In a statement released that day, the DA says, “the People continue to maintain defendant’s guilt of the very serious charges in the indictment.”

Though Churaman and his supporters celebrated the case closing, he sees the outcome as a loss for himself.

“I lost my childhood, I lost a large chunk of my young adult life,” he says, listing things he knows are irreplaceable. “No price tag, no dollar amount, will ever equate [to] what was stolen from me.”

But Churaman’s case extended beyond himself, through those who raised awareness and helped fight for his freedom.

“All the comrades, all the activists, advocates, people that are fighting for exactly what I was fighting for alongside me, that is what I consider a victory,” he says.

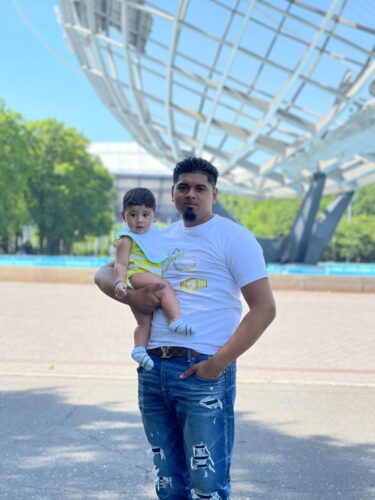

Churaman has been free for several weeks. As of June, the former Rikers inmate is left leaving picking up the pieces of years lost… Churaman’s circle now consists of those who fought with him and a few family members: his mother, his partner and his infant son.

When asked about his hopes for his son, he pauses to think. “I hope [my son experiences] the exact opposite of what I was forced to live.”

Churaman plans to teach his son about his constitutional rights, the knowledge that he didn’t have until it was too late. (He says that if he knew about the 5th Amendment at 14, he would’ve remained silent.)

“I hope, I pray that God just gives me the energy, the blessings to be there by his side, to watch over him, to protect him, to guide him, to educate him.”