Bright lights, late nights, glamorous gatherings with endless opportunities to preen and extravagant aesthetics; life in fashion is often assumed to be a grand soiree in itself. And when an up-and-coming designer is spotted hanging out with the likes of Riz Ahmed, at a pre-Oscars party celebrating South Asian excellence, it’s fairly easy to assume privilege and kinship. But they say, never assume the obvious is true.

In a recent sit-down with Brown Girl Magazine, creative head and designer Zain Ahmad used the following three words to describe his swiftly growing streetwear label Rastah: “identity, struggle, community.” There is no denying that fashion is a form of self-expression. Fashion is also a reflection of culture, community and politics and it has the power to challenge norms, initiate movement and pave way for social change. But for a South Asian label to unite these multi-dimensional abilities of the fashion realm in complete harmony whilst also being an extension of the founder’s own struggle with an identity crisis is not a common sight.

View this post on Instagram

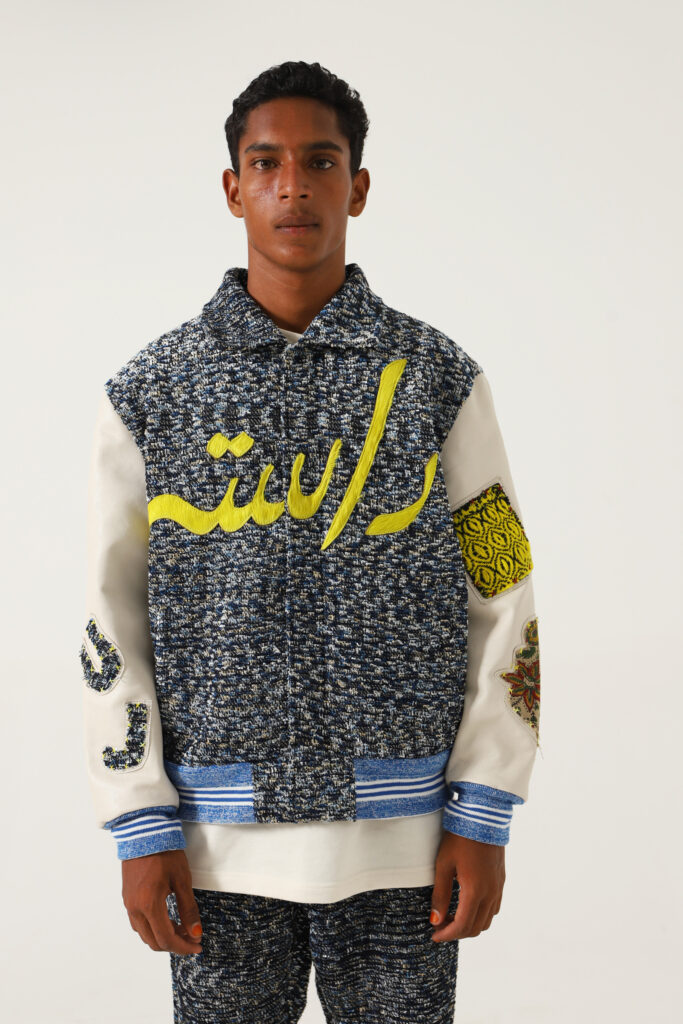

Having lived in multiple cities across the world, Ahmad, who now collaborates with celebs like Anil Kapoor, Harshvardhan Kapoor and Academy Award winner Riz Ahmed, always had a hard time fitting in. In a sea of quintessentially ‘white’ personalities, Ahmad would often find himself either defending his Pakistani roots and identity or dissociating himself from prevalent stereotypes and preconceived notions. Eventually in 2018, together with Adnan Ahmad and Ishmail Ahmad, he founded Rastah — a symbolic representation of the social struggle Ahmad overcame as a growing individual, finding solace and pride in his brown-ness. Since then Rastah has become a raging success; a hip, edgy, relevant streetwear brand that sustainably combines indigenous South Asian artisanship with a more contemporary design ethos. It has carved its own niche of admirers who look past its luxury price tag and find meaning and passion in the experimental and futuristic art it has to offer.

[Read Related: KiRu: The Indian Streetwear Brand Reshaping Fashion’s Gender Rules]

Our conversation with Ahmad delves into this intimate design process that Rastah follows, the narrative it has established for South Asian creators looking to smash the old rules of the establishment and the pathway it’s creating for local artisans by positioning and promoting their craft in the global fashion landscape:

We know Rastah is a brand reinterpreting South Asian culture, craft and design forms. But what more is to the label and its mission than just being a reflection of the local culture?

Rastah is pretty much a reflection of who I am as an individual, encompassing all my flaws, insecurities, things I appreciate about myself and even things I may not like about myself. And the sort of distorted, edgy aesthetic that people get to see is more a culmination of me as a brown person having lived in so many different parts of the world, struggling with my identity. I reflect on this now that as someone who lived in the UK and in Canada, I would often find myself in a situation where I would forcefully try to fit in. I’d be at a table with a bunch of white friends and would hear a passive aggress joke, that may have not been intended to be racist, but I’d still find the need to say that “hey, I am not like all the other brown folks you see out there.” So Rastah is an extension and/or a representation of me getting out of that shell; rediscovering my identity and celebrating and championing my heritage. And I feel this is something that many people can relate with. We are still stuck in a post-colonial hangover of sorts. We are still not fully rooted in who we are and who we want to be. So Rastah is for everyone out there who just want to be themselves.

On the modern, edgy aesthetic, when exactly did your love for urban streetwear began?

I used to live in Vancouver and Vancouver is a very multi-cultural city. I noticed that fashion is such an important means of communicating not just where you’re from but also who you are, what you’re feeling, what’s so deeply rooted inside you. I also found it very interesting what people like Virgil Abloh did within the streetwear scene, turning streetwear over its heels and giving it a new meaning. Over the last decade, we have seen fashion completely transform through the lens of streetwear and that’s when I realised that streetwear isn’t about the clothes; it’s about the narrative and the emotions behind it; what’s important is the story behind the clothes and I love storytelling.

Around that time, I thought to myself there’s so much more I need to discover about myself, maybe I should go to back to Pakistan and learn more about my country’s heritage and craft. That’s how Rastah came about. Honestly, I don’t think I can guarantee whether or not I’ll continue to do fashion in the future but what I can guarantee is I will continue to tell stories. I have aspirations in writing and in filmmaking so the story really is the main core of the whole idea.

You haven’t trained or specialized in fashion design?

No. I taught myself everything from scratch which I believe ended up being a blessing in disguise, because for me, there were no rules. In Pakistan, fashion practices are very boxed; there are rules to be followed. And then when you have this newcomer who is actually a political science graduate and knows absolutely nothing about the industry, you just throw yourself in and are of the mindset that I am just going to discover as much as I can. And that’s when you start to redefine the rules for yourself. Maybe it’s why Rastah caught people’s eyes. They were like, “oh, what is he doing? He’s using these prints that aren’t supposed to be used in this way. It’s interesting but strange.”

What’s the journey of establishing the brand in Pakistan been like? Bringing local craftsmen on board, setting up the business and making it lucrative; it’s a business at the end of the day. What have been some of the challenges?

The business side of it was definitely a struggle. I went into it thinking it would be a world of utopia and things would just fall into my lap and we would just be creating amazing things. But unfortunately the canary in the coal mine was hinting at it not being that way. One of the biggest problems I noticed was that craft, in general, in Pakistan was either dying or already dead. And so it was a struggle getting these artisans to trust the brand, its mission, its longevity and the creative process. Over the past two decades, these craftsmen had met many people who made promises but never really saw them through. So the first step was to be able to build an environment and a culture where there’s a symbiotic and collaborative relationship between artisans and the team.

[Read Related: Rootsgear: Streetwear that Makes a Statement]

And then turning this creative collaboration into a lucrative business has been very difficult as well. What people fail to understand is that when you’re trying to create a brand, you may not see the cash coming in right at the beginning, because building brand equity comes before making money. Now we’re in that phase where we’ve built a bit of brand equity which is transitioning into sales. It’s a balancing act where you create products that suffice your needs as a designer and work as an outlet and you’re also creating products that are easier on the consumer and easier to sell. For instance, the t-shirts and the hoodies we make, may not take as much time and effort in designing but for consumers they are easy pieces to not only wear but also to buy into the brand. Whereas I may take six months to design a jacket that looks absolutely crazy and I would personally want to wear it every day but not everybody’s going to want to wear it or love it for the same reasons.

Also it’s important to be very operationally sound and have a key component within your business that is able to manage all of the day-to-day hurdles. Luckily, we’ve built a team where everybody is able to work on every single role and we are also so closely tied to the supply chain. If I was living in Canada and trying to run Rastah in Pakistan, it would be an absolute shit show of a disaster. But because we are here and so closely knit, we are able to solve those problems in real time.

We’ve established that Rastah is an extension of your personal experiences and perceptions of the world, but where do the artisans and other members of the design team sit in the entire creative process of making a Rastah collection?

The process for every collection always starts with a narrative. It’s going to be me writing down a story; I’ll sketch, my team will make sketches and then we use those sketches to create a palette for the fabrics, for prints and textile. That’s when the artisans start to get involved where I’ll ask Aslam sahab (crafter) for suggestions on prints and designs that would fit into the palette. He’ll come back to me with his input and then we head to the weavers and ask them that this is the sort of texture looking for and what do they suggest should be done in order for us to achieve what we’re trying to achieve. So the design process is very collaborative. If you take even one person out of it, the whole thing would collapse.

And how do you come around to selecting the quotes and phrases that one can often see in Rastah’s pieces?

We’ve made this a practice at work where I tell my team that if they feel there’s a certain quote that would make sense — it doesn’t even have to come from a famous person; it could just be something sitting inside of them, let’s put it on the garment because there’s probably a chance that a lot of other people are feeling the same way too. For example, the next collection has a phrase incorporated through out the collection. It says that even the emptiness within your heart has a sound to it. So together we just see and gauge what’s really sticking with us and would also make sense to the consumer.

About your comment on designers making promises and then not seeing them through. Would you call Rastah a ‘fair trade, fair wage streetwear brand?’

Yes, absolutely! What I’ve told my artisans who have been working with us that this is going to be a process over many years. Around three years ago, we met this weaving family in Kasur and the Master sahab told his kids that this is probably just temporary, he’s (Ahmad) come to get this little swatch made and he probably won’t come back again. But that three yards of a swatch turned into 30, which then turned into 300 and is now close to a 1000. So, it takes a lot of time to not only be able to build that level of trust but also be able to pass on the confidence to the artisans that they have ownership involved within the products.

The other thing is that because of the way we have priced ourselves and because of our higher gross margins, we’re actually able to bear artists on five to 10 times more compared to what a normal brand in Pakistan would be able to afford. What we pay the artisans is what a normal brand would be retailing their products at. Our price point allows us to set aside a cushion to pay them fairly.

We are now incorporating an interesting element to the model. A lot of our artisans also have their own creations. It can be a tapestry, a rug, a tablecloth. What we are now doing is that we’re giving these artists a platform to sell these products on our website. The brand value allows them to sell these products for a lot more than what they would get locally and they get to keep the money. What it does is it instills this feeling of confidence and hope in a person’s abilities. It provides them another income stream.

View this post on Instagram

Circling back to our discussion where you mentioned that fashion in Pakistan is relatively boxed. And even with Rastah coming out and so many other young talented artists pushing the envelope, we still haven’t reached that level of global appreciation as our other South Asian counterparts. What do you think is lacking in the industry’s as well as the society’s overall approach?

The mindset of mass consumers in Pakistan facilitates a certain kind of a business. A lot of our big, fast fashion brands cater to this mindset. The consumers want to see the very cheesy campaigns and the same trends. And it’s making designers tonnes of money so they don’t feel the need to step out of their comfort zone.

The challenge is when someone in Pakistan tries to do something different they are completely disregarded and scrutinised, so challenging the narrative then becomes very hard to do so. In India, for instance, any start-up that comes up is championed locally before it gets championed abroad. Over here, it’s the other way round. Because we are still dealing with this post-colonial hangover, we first need to get the stamp of approval from the ‘white’ population before we get a thumbs up from our local audience. I don’t think Rastah would’ve been where it’s at, had we not been published in Vogue, had maybe Anil Kapoor not worn our clothes, had Riz Ahmed not worn our clothes or Karan Johar. All of these people have led to local consumers thinking that if they are saying it’s a cool brand, then it definitely must be. So we need to get rid of that mentality in order to make waves in the broader market.

[Read Related: Designer Arpita Mehta on her Craft, Artisans, and 2021 Trends]

Rastah — drawn from an Urdu word meaning path or journey — is definitely making waves with its pathbreaking business model and approach to streetwear and its unique, personalised reinterpretation of Pakistan’s inherent craft. And with global affiliations already underway, it’s set out on this journey of making a statement for Pakistani and South Asian representation on the global stage. In fact, the brand’s latest collection doesn’t even feature models. The label, with the help of a local 3D company, has created a whole universe where digitally crafted models can be seen wearing the pieces and resonating with the brand’s newest, rather trippy idea. It’s the sort of evolution that the local Pakistani fashion scene has been yearning for. It’s not just connecting consumers with clothes, it’s giving them an avenue to express themselves, define their sartorial identity and form an intimate relationship with fashion.

Photos Courtesy: Zain Ahmad