We at Brown Girl Magazine are excited to launch our very own literary section featuring original work by South Asian writers from all over the world. With Nimarta Narang at the helm as editor, we aim to publish one piece of original fiction per month along with an interview profile of the author to discuss all things storytelling, writing and creating.

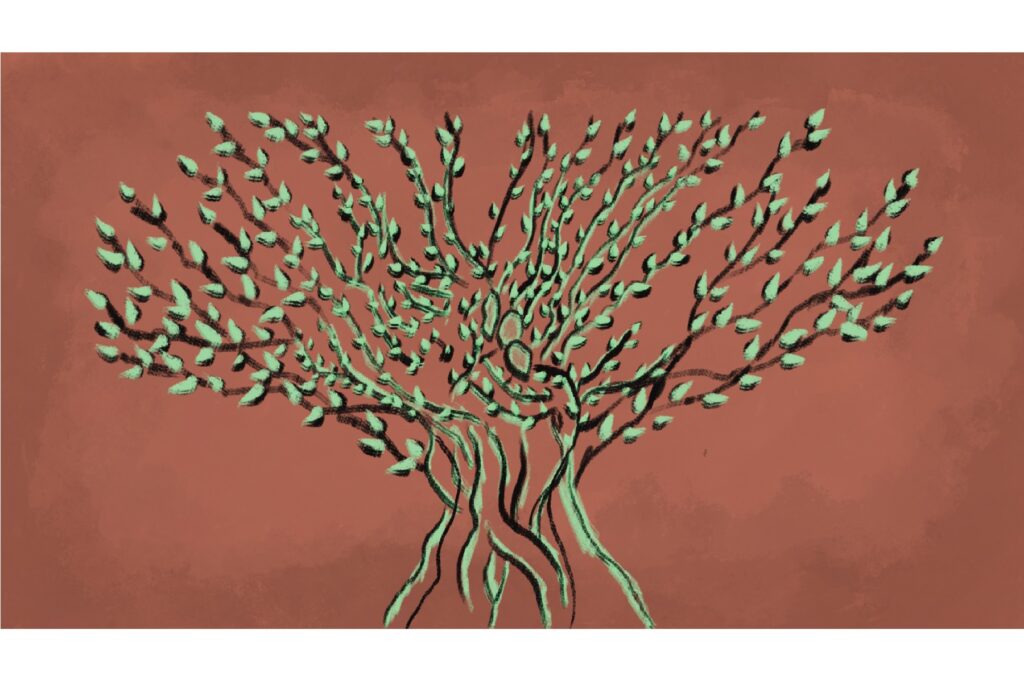

In this piece called ‘The Banyan Blooms,’ writer and activist Malavika Kannan delves into the folklore of generational curses and how it manifests in the relationship between a great-grandmother, mother, and granddaughter. In this story, Reena learns that her great-grandmother has passed away in India. She embarks on a trip with her sister and mother on a trip to Chennai from Cleveland to attend the cremation. Kannan’s thought-provoking and lyrical words about trauma, mental health, and family customs are presented with a level of honesty that will leave the reader stunned. The artwork is created by Aisha Shahid.

View this post on Instagram

- The summer Maaji curses me is the summer the banyan blooms, and so do I.

My hips swell wide like they’re trying to bridge the oceans between me and the motherland. My thighs become two continents clashing, stretch marks like a map of fault lines. So naturally, when news of Maaji’s death arrives, my little sister, Lavi, taps my belly and asks if I’ve swallowed her.

“Your great-grandmother,” Amma says at the dinner table, “was very old, and crazy too. It was only a matter of time.” It’s cold in Cleveland, and the thin apartment walls are starting to ache. I stare at steel skies through the window.

Lavi nods, but I know she doesn’t understand. I feel a shiver in my bones as she stabs pasta with her fork. She smells like salt, dripping with life, too boundless to concern herself with matters of crazy matriarchs. After a moment, she asks, “So did Reena eat her?”

Amma starts to sob. Lavi stares at me, Maaji’s devourer, for an explanation, but I have none. In my fourteen years, I’ve seen Amma cry countless times. She was diagnosed with depression the same winter Maaji was diagnosed with dementia. Her meds make it better, but last week I came home and found Amma in the kitchen, crying on the phone with nobody on the line. I didn’t even take off my shoes. I stood there, staring. The moment wasn’t meant for my eyes.

“I swear I didn’t swallow her,” I tell Lavi. But I bare my teeth at her so she knows I’m capable.

Amma slips into her bedroom, but I stay with Lavi at the table, arranging the flecks of food she spills into patterns on the plate.

Maaji has been lost for years—the fizzling of her pulse only sealed the deal—but it feels like she’s taken parts of me with her, leaving me hollow, boneless, scooped out like a melon. Without her, what is left?

“Reena,” Lavi ventures. “Do you think Maaji remembered me?”

[Read Related: Meet the 32 Authors Behind ‘untold: defining moments of the uprooted’ — Brown Girl Magazine’s First-Ever Anthology]

I look at my sister, her eyes bright. I can’t find the words in me to answer. The last time we saw Maaji was two years ago on a family trip to India. (Having immigrated before Lavi and I were born, Amma thought it important for us to know our motherland. But we never stayed for more than three weeks at a time. And no matter how much Maaji begged her, we never returned for good.) By then, Maaji could no longer name me, not even when I bled as a woman for the first time on her porch. Amma was mortified, but Maaji held me close. She unspooled a story about a queen so lovely she was besieged by demons and had to lock herself away in a tower. To defend her honor, a thousand strong suitors rushed into battle, but they were cut down like too-ripe fruit. The beautiful queen was out of options. So she prayed to her mother, and when the demons stormed her tower, she spread her legs wide, drowning them in her blood.

Maaji often told tales like these, weaving fact and fiction like the roots of banyans. Afterward, she warned me about curses: generational curses, paternal curses, fraternal curses, maternal curses, and everything in between. (Curses, she told me, were our ancestors’ insurance policy against being forgotten. If they felt angry, or even bored, they’d rebirth you as a tree, erase you from your lover’s mind, or slowly rot away your molars.) Amma did not approve of Maaji filling my head with lies: she made me swear not to repeat her words to Lavi. “She’s insane,” Amma said firmly, at my protests. “And I’m afraid she’ll take you the same way.”

Beneath the dinner table, I take Lavi’s hand. It’s warm, bird-like in mine. “I’m sure she remembered you,” I lie. “Who could forget you?”

Amma returns holding three slips of paper—plane tickets, dated for tonight. “Reena, help Lavanya pack,” she says. “The cremation takes place tomorrow. Our family is waiting for us.”

Family. I turn the word over in my mouth. To me, it tastes flat, all stiff American vowels, but when Amma says it, it feels bitter and complicated as sugarless chai.

“I don’t understand,” Lavi chirps. Amma sighs, and when she speaks, I hear it in her voice: an age-old fear, so dark and damp that a hundred people are drowned in it. “It means that we’re flying to Chennai,” Amma says. “We’re going home.”

- Home, as it happens, is 8,000 miles away, which means seventeen non-stop hours in an airplane with Lavi, who clamors for the window seat. She swipes through cartoons on the seatback screen with intense concentration. When the plane finally lurches off the runway, she still hasn’t picked one out.

“Lavi,” I whisper. “Look out the window.” If I look over her head, I can see the earth and sky colliding, our hometown slipping quickly from view—another instant, and it’ll vanish.

She doesn’t blink. “Lavi,” I hiss. “Let me see, then.” Lavi pretends not to hear me, busy with her cartoons. I look to my right: Amma is safely asleep, having taken her pills. So I pinch Lavi, and she shrieks, loud enough to make the flight attendant scowl. I cover her mouth with my hand.

“Why’d you ask for the window,” I demand, “if you weren’t even going to look outside?”

“Because I’m scared of heights,” Lavi pouts, shutting the window.

She ignores me again, and I simmer, but not for long—Lavi, predictably, falls asleep ten minutes into her movie, and I reach over and open the window. The sun’s set, but if I squint, I can make out thin streams of car headlights chugging like arteries from the heart of Cleveland.

“I have a question,” Lavi murmurs from under my arms—I thought she was asleep, but she’s been watching me all this time through slitted eyes, her breathing soft and steady. She hesitates. “How did Maaji die?”

It’s the first time Lavi’s used the word die. Six years of age—old enough to cut her own crusts, tie her own shoes—but she still skips the death scenes in movies, speaks of our dead hamster in the present tense. Maaji, however, spoke of Death at length: a lovesick god who quarreled with his human girlfriend, swearing never to return to her. He kept his word. For seven yugas, the lover roamed the earth, centuries-old and unable to die, waiting for Death to claim her once more.

“It didn’t hurt at all,” I say. Then I add, “Maaji died like a banyan tree.”

“Oh,” says Lavi. She’s comforted, because I wasn’t lying, not really. Once Maaji filled her mouth with seeds, knelt in the earth, and asked God to make her a banyan. And when she died, she was strong, unyielding until the very end. She held my world hostage in her roots.

- Nobody claps when the airplane lands, and that’s how I know we’re home. Lavi doesn’t open the windows, but I feel the land drawing us in: tempting, unruly. When we climb off the plane into the clay-baked sunshine, Chennai consumes us. “Don’t make eye contact with anyone,” Amma warns, peering nervously at the loitering men. She tugs us through the arrival area, clutching our American passports like amulets until we find our family.

They come laden with food: mango pickle, yogurt, Thermoses of tea, chapatis wrapped in foil so we can eat with unwashed hands. My grandmother marvels at my hips, well-cushioned for childbearing, and congratulates Amma for feeding me well. My uncle Raju pulls a shiny rupee from Lavi’s ears.

My grandfather pulls up in an enormous love van from the ’60s. The seven of us pile in and speed off in a cloud of gasoline. “How is America?” my cousin Hari whines. “Have you been to Disneyland?” He’s wearing a faded, hand-me-down shirt with a star-striped flag on it—possibly my uncle Raju’s idea, to make his foreign nieces feel more at home.

I want to tell him that we live in Cleveland, not California, but Lavi sits up and says, “All the time. Once, Mickey Mouse invited me to Disneyland for evening tea. It was simply divine.”

Hari is awe-struck—whether it’s her far-fetched story or her breezy American cadence, I can’t tell. But my grandmother laughs. “When this one speaks,” she says, “Maaji is reborn.”

“Maaji,” protests Amma, “was crazy like a bird.”

“Maaji,” says Lavi seriously, “died like a banyan tree.”

Amma scowls but says nothing.

The van chugs out of Chennai and into its rural surroundings, brick buildings giving way to clay huts and fields spilling with crops. We stop outside a low white building. “Where are we?” Lavi asks, but I don’t respond. I know the answer, because the women pull their shawls over their faces, locking hands like they’re entering a battleground.

“This is the rural hospital,” says my grandmother. “We’re going to the morgue to bring Maaji’s body home.”

“Stay in the van if you value your sanity,” Amma warns me. “Even the air here’s like poison.” Then she disappears. Her speeches are never complete without an omen of doom.

Still, I do not stay in the van — partly because it’s too hot, but mostly because Lavi has brought a Wonder Woman comic strip and is reading it aloud in perky English to impress our cousins. “Lavi,” I hiss, pinching her for attention, but she doesn’t even look up.

Something twists inside of me: anger, grief, I don’t know — only that I can’t watch Lavi for a second longer. I’m tired of how easy life is to her, how untouched she is by this sadness, how she treats even a funeral like her own personal talk show. Really, I need to breathe air that my loud-mouthed little sister hasn’t already exhaled. So I leave her behind. Lavi is too busy with her audience to notice when I slip out of the van and walk into the morgue.

It’s clean and dim inside, the fluorescent bulbs blotted by insects attracted to the light. At the end of the hallway, I find a room lined with curtains, so warped and membranous that I can’t see more than a foot ahead.

I push aside the curtain, but I don’t see my family. Instead, I see a young boy, his brow smeared with ash. He’s using a branch of reeds to fan the kingdom of death.

Maaji told me stories about it, but she couldn’t have prepared me for it: the womb-like morgue, heaped with darkened shapes, each wrapped beneath sheets as if simply asleep. Except these corpses are humming: sweetly, sadly, the sounds brushing my ribs before nudging aside my heart. Their voices ooze like jaggery, sticky with death, drawing me closer. Warning me.

The boy’s head jerks up at the sound of my footsteps. He yells something at me in a language I don’t know. His fan snags the veil on the corpse nearest to him, and I catch a glimpse of the face. It’s Maaji.

I feel my organs sink low. The corpses sing louder. The blood deserts my face. For the first time, I see Maaji exactly as she is: old, cracked like a glass dish, the fables stale in her cold mouth. “I’m here!” I want to shout, but I can’t find the words. She’s not inside that body, I realize. She never was. She’s not sane, she’s not alive, she’s not anything at all.

And it’s almost as if Maaji hears my thoughts: the woman who taught me about curses, who taught me that forgetting is the greatest curse of all. Because before I can react, I feel something rising up in me: something snarled, boundless, inscrutable as the marrow in my bones. I know what it is because she taught me. I know that it’s her curse.

“I’m sorry,” I gasp, too late.

The boy screams at me, this time in English: “Get out!” His voice is shrill like Lavi’s, not yet swelled into a man’s. I stand over Maaji’s corpse, my own body trembling. “The ancestors,” she once told me, “can curse you through mirrors, possess you through photographs.” Maaji even painted over the faces in our family portraits so that ancestors couldn’t escape through the frames.

The boy swats at me with the reeds, sending the curtains fluttering like open graves. He doesn’t need to tell me twice. I stumble out of the room just as Amma, uncle Raju, and three nurses appear in the doorway. At the sight of me, Amma’s face twists with rage. “What are you doing here?” she says.

She hates when I disobey her. For a moment, I consider telling her that Maaji has cursed me. But then she’d lose it, for real. So I stay quiet. Meanwhile, the boy wraps Maaji’s body back in the shawl and rolls her out on a gurney. My grandmother blesses him and gives him a rupee.

“Reena,” Amma hisses, once he’s disappeared behind the curtains. “I told you to wait in the van. It’s bad fortune to visit a morgue. Are you all right?”

I struggle to keep a straight face. Do I look insane? I certainly feel that way.

“I think so,” I lie, and she leads me back to the van.

I don’t say anything after that, because Maaji’s curse is burrowing into my blood, finding roots inside of me. To me, it feels like seeds buried deep, but to her, it feels like deliverance.

- Eight people are crammed into my grandfather’s love van: six living, one cursed, one dead, although it’s not immediately obvious who is which. Lavi, who’d shrieked at the sight of Maaji’s corpse, now sleeps fitfully on Amma’s lap, and my cousins are quiet, spellbound by the corpse in the trunk. Amma begins to pray, fear puddling in her words like glue. My skin feels ill-fitting like I’ve shrunk in response to Maaji’s curse.

My grandmother clutches her heart and sighs with relief when we reach Maaji’s ancestral homestead. “Now Maaji can rest easier,” she says. Through the window, I watch my uncles build a pyre beneath the banyan tree. “Seven generations of women were sent off to the afterlife in this home,” she adds, noting my gaze. “We’ve never missed a death.”

It’s going to be a full house—I can tell from the piles of shoes stacked by the door, as if on display. On cue, a woman in white spills out of the house, smothering me and Lavi in her shawl.

“My lost children,” she cries. “You’ve flown home like birds stolen from their nest.” She asks if we remember her: Lavi does not. “My poor bird-child,” she says. “I’m your perima, Preeti.”

Amma climbs out of the van with Maaji’s body. Preeti Perima gasps—not at the corpse, but at her living sister, our mother. “Lavi has forgotten my name,” she says, and tears spill out: monsoon season. “Did you let her forget her language, too? And that old woman in your arms?”

Lavi sulks, but Amma says nothing. She touches the feet of our elders, and I do the same. I expect someone to flinch, sensing my curse, but nobody does. Nobody notices that the seams of my body don’t match my insides. That I’ve been cut out of my soul and stitched back in reverse.

Inside, Lavi and I take turns hoisting each other over the toilet hole. While the adults build Maaji’s outdoor funeral pyre, we lay on the veranda to watch, Lavi’s arms crossed over her body like a coffin.

“Who stole me from the nest?” she asks. I can tell this has been bothering her.

“Nobody,” I say. “Preeti Perima’s a loon. It’s because you grew up far from India.”

“Well, I couldn’t be a bird,” says Lavi. “I’m too scared of heights.”

“Yeah, you couldn’t be a bird,” I echo, but I’m lying. In the twilight, Lavi looks just like the finches we studied in biology class: small, slender, bones light enough for flight. I wonder if we’ve evolved on our island across the sea. I wonder if it’s for our own good.

We sit for dinner with one empty chair. The women orbit the table like planets, refilling plates, nodding attentively while Lavi chatters, though I know they don’t understand her rapid English. I let her do most of the talking. Hello, I say occasionally. No, I’m not hungry. Nobody says the things I hear on American TV: God has a plan for her. She’s in a better place.

Preeti sniffles over the sambar. “Your little one is loud but forgetful,” she tells Amma. “Perhaps you’re not feeding her as well as the older one. Reena is larger than your new nation.”

“Lavanya’s only six,” says Amma. She is patient: Sisterhood, after all, demands that you keep your eyes steady when they cry and your mouth closed when they talk. But Preeti sighs.

“Maaji is dead,” she says. “When we die, will these children gather? Will they remember our names?”

Of course we will, I want to protest, but Amma leans forward in her chair. “My children live in two worlds,” she says, “but they remember everything. Their roots are as wide as trees.”

“Trees can be nipped in the bud,” Preeti says coolly. “And what about you, my sister? Home for the cremation, and nothing more. You know, Maaji went crazy because you left. You’d broken her roots.”

At the sound of Maaji’s name, the curse in me awakens. It roars inside my blood and Amma bursts into tears. I wish I could switch places with her, become her mother, wipe her eyes and comfort her. I open my mouth to speak, but Maaji is faster, and instead, I hear myself scream, loud enough to scrape my throat.

“Chellam, what’s wrong?” my grandmother asks, but I only scream louder.

“Reena, stop this at once,” Amma says. Her wet eyes gleam like coins.

“Something’s gotten into Reena,” Preeti shouts, gleeful. “She’s crazy like the corpse in the field!”

Amma, stronger than she looks, wraps herself around me. There’s terror in her eyes. She knows I’m done for, that I’ve gone the same way as Maaji. I curl inwards, but Amma pries me back open. She blocks out the world with her body, and into her body, I shriek. I shriek so loud I almost don’t notice the second voice harmonizing with mine.

Lavi is standing next to me, her eyes screwed shut, screaming in sisterly solidarity. She doesn’t know why she’s screaming: She doesn’t know I’m cursed. But the shock is enough to make me slacken in Amma’s arms and take a deep, slow breath.

“Amma,” I try, but she pinches my arm. She won’t look at me.

“Be quiet, Reena,” she says. “You’ve embarrassed us enough.”

To fill the taut silence, Preeti immediately starts talking, and soon she and Amma have apologized to each other. Together they clear the table, giving everyone an excuse to settle into bed.

[Read Related: 7 Women Afghan Activists and Creatives to Support Now]

But I do not sleep. In the darkness, Maaji sings louder in my ears. I think about the last time I saw Maaji over Skype. She’d asked for me, of course, and Amma had scowled: she was always wary of Maaji’s pixelated voice. But this time, Maaji was weak. She mumbled incoherently until Amma hung up. As the call ended, I saw Amma’s relief, and that’s when I knew: Amma’s always on the run. She trips over telephone lines, trying to escape her homeland and her lineage of mad women. But how do you outrun something that seeps through your own blood?

Something’s gotten into Reena, Preeti had said. She’s crazy like the corpse in the field.

At some point, it’s all too much. I stand up in the dark and tip-toe through the courtyard, careful not to step on distant family members sleeping on reed mats to stay cool. I stagger outside and let the fevered air wash over me. That’s when I see it: the old family banyan tree, replete with strangling figs. It’s next to Maaji’s funeral pyre, standing sentinel over her body. The tree that Maaji tended as a little girl, now grown warped and wide, its roots a forest of its own.

Shards of sky glitter through the branches as I climb the banyan tree. It’s been years since I’ve last climbed it, but my body remembers where the toughest roots hang, where it’s safe to trust my weight. For a moment I sit in the tree, mosquitoes whispering around me. Then I hear more rustling beneath me: A pair of luminous eyes peers up from the ground.

“Reena?” Lavi calls, and I nearly scream. How did she manage to follow me here?

“Go back inside, Lavanya,” I say, using her full name. I don’t say, I’m scared. Or, I’ve been cursed. Or, I’ve never felt more alone.

Lavi squints up at me. “Amma said you’re crazy,” she announces. “She told me I had to stay away from you. Why would she say that?”

“She said that?” My heart falls.

“She said Maaji ruined you,” Lavi says. “Was that true, too?”

Rage transforms me into a live wire. The words slide sharp and slick from my mouth.

“You’re just a stupid little kid,” I say, and Lavi’s face falls. “I’m broken in ways you can’t understand.”

I want to stop shouting, but I can’t. “Why don’t you stop following me around? You don’t know me. You didn’t know Maaji. That crazy woman died, and I’m going the same way, and all you do is chase me with your questions.”

Lavi’s lower lip trembles. She clambers on the funeral pyre and grasps the tree, but she can’t climb more than a few feet before she slides back down. I can feel her heart throbbing like a bird in a cage. She’s too afraid to climb, which means she can’t reach me. At that moment, I’ve never felt freer.

Eventually, Lavi gives up, and after I’m sure she’s gone to sleep, I follow her into the house. But when I finally fall asleep, Maaji doesn’t spare me. In my dreams, I see her. She hands me a knife and instructs me to stab Amma, Preeti, Lavi, and the other women. If I don’t, she’ll burn us to death. She tells me to choose our deaths between knives or fire. I still haven’t decided when Amma shakes me awake.

- Amma is stiffly silent as she dresses me for the cremation, but she cannot hold her tongue for long. She’s squeezing me into a sari—snow-white for mourning. “You don’t fit your Indian clothes anymore,” she complains. “I feel like I’m squeezing toothpaste back into a tube.” She tugs the zipper of the sari blouse, clearly too small—I heave and struggle. The zipper breaks, and so does she.

“This is my fault,” Amma says. “You could never control yourself, Reena.” Her arms hold me viciously tight. “You listened to her crazy stories, and now you’ve been disobeying me, screaming and mocking your Maaji’s deathbed. And what’s worse, you’re influencing Lavi. By the way, she’s telling everyone that Maaji’s not dead, just living inside the banyan tree. Did you teach her that?”

I feel small. “Maybe.”

Amma wipes her eyes, bangles clinking. “From now on, you keep your stories to yourself,” she says. “You know that madness runs in our family. I can’t let you bring your sister down with you.”

Words climb like vomit into my throat.

“Your sister Preeti was right about you,” I snap, tugging myself from her grasp. “Maybe you’re the one who broke the roots. And this madness?” I laugh, much too loud. “You’re the one who raised me, so far away from family. So if anyone made me crazy, it’s you.”

Amma gasps, but just then Preeti opens the door to the dressing room. “Hurry,” she tells her. “There’s too much wind in the air. We have to cremate her soon.” Preeti flinches at the sight of me. Her eyes look like demands: Be normal. Be good.

“You hear that, Amma?” I say before I can stop myself. “It’s time to burn her up. Nothing left but ashes. Lavi never even heard her stories—”

She slaps me, shocking me. “Get out,” Amma says. “I don’t know you anymore. I never knew you at all—”

At first, I can’t hear her voice. All I hear is the curse in my ears, rushing like a storm.

Then I rip my hand from Amma’s. For the second time, I find myself running towards the banyan tree. But this time, I’m ready. I know what I have to do.

[Read Related: Book Review—‘Girlhood: Teens Around the World In Their own Voices’ by Masuma Ahuja]

My relatives are gathered around the funeral pyre—Lavi, thankfully, is nowhere to be seen—stoking the flames where Maaji must burn. At the sacred hour, they’ll transfer the flames to her body. But there’s no time to wait. She holds me hostage in her roots.

Before anybody can stop me, I seize the nearest oil-rag torch, dip it in the flames—it catches easily, roaring to life like a great fiery paintbrush.

Then I set my great-grandmother’s body on fire.

To her, it feels like flesh turned to ash. But to me, it feels like deliverance.

The pyre crackles sharply, consuming her body, roaring, divining. I start to walk away. Somewhere, somebody begins to scream. I turn to see that the banyan, too, has somehow caught fire. Has Maaji’s funeral pyre blown in the wind? It doesn’t matter—I feel a thrill of power.

Amma is standing beneath the banyan, waving her arms, Preeti and the women gathered around her. Uncle Raju and the men are rushing past me to get water buckets, my cousin Hari chasing excitedly behind, glad to be let in on the action.

Meanwhile, the fire is catching, spreading through the tree.

Good riddance, I think, as the roots flame like a halo. Once, Maaji prayed to God to make her a banyan tree. Now, I pray to God she’s trapped in its roots forever.

Amma turns to me, and something inside her seems to break. “Reena!” she cries. “What have you done?”

The heat is coming from the tree, but I feel it most acutely inside my chest like the fire was lit inside. In spite of everything, the air smells sweet: smoky bark and loosened earth.

“Reena,” Amma gasps, and she points to the top of the banyan. And then I see her.

Lavi’s at the top of the banyan tree, clinging to its branches. At first, I can’t understand what I’m seeing—how did she get there? She must have climbed up when I wasn’t watching—to prove herself to me, to care for me, to burn with me? I don’t know. But when I look at her, I see all the places Maaji put herself to rest. I see her with more certainty than I’ve ever seen anything in my life.

“Reena!” Lavi reaches for me, eyes bright. She’s trapped.

Fear turns my bones to liquid, and I reach up for Lavi, but I’m too small, too far, and flames sear my hands instead. “Lavi!” I cry. Desperation pounds through me—no water buckets, no men, no savior, no deliverance but ourselves. There’s only one thing left to do.

“Reena, what are you doing?” shouts Preeti Perima, but I ignore her. There isn’t a choice.

I grasp the lowest branch and start to climb the burning tree. Amma screams as I climb through the corkscrewed roots, embers catching, skin burning, the eye of the storm. I feel the heat, I gag. Fire fills my lungs, but there’s no pain. I think of Death’s lover, roaming listlessly on earth, and isn’t it such a blessing, really, to have your love scorched into the sky? And then I wrap Lavi in my arms, my body shielding hers, and Maaji’s curse shielding mine. I surrender to the air, our bodies fluttering like candles.

But I don’t truly feel Maaji—all I feel is my sister, warm and airborne, blazing with life.

Because while Maaji died like a banyan tree—strong and unyielding until the very end, holding the world hostage in her roots—Lavi wriggles, soft as a sapling, unending in ways I can never understand. Her flesh buries me, roots me. Even the sky can see that these roots run deep, and they hold fast.

Artwork coursesy of Aisha Shahid.