As a first-generation South Asian American girl, I remember questioning ways my culture didn’t fit into the worldview my parents were raising me in.

“So why do women need to serve men their dinner first? Can’t we all just eat and enjoy together?”

“Why would people ever drown their infant girls in other countries?”

My mother, aunties and the strong South Asian women around me often understood these questions. Yes, it is unfair. Yes, it‘s not right. It’s why we are raising you here, beti.

The sacrifices my parents made, like so many immigrants who came to America on the cusp of the Civil Rights Movement in the ’70s, are what awarded me and many of my fellow brown first-generation sisters the freedom to question openly. To aim high.

It’s why days like The International Day of the Girl Child are important for WOC writers, creators and artists to rise up and support those who are speaking up and advocating for many girls that are just like us; just like our own daughters.

International Day of the Girl Child, declared a decade ago by the United Nations, celebrates the importance, power, and potential of girls around the world. It also highlights the barriers they still face to get there.

[Read Related: #InternationalWomensDay: What Does it Mean to be a Girl?]

Did you know that up to 10 million girls will be at risk of child marriage and girls are primarily victims of sexual exploitation as 72% of detected girl victims globally?

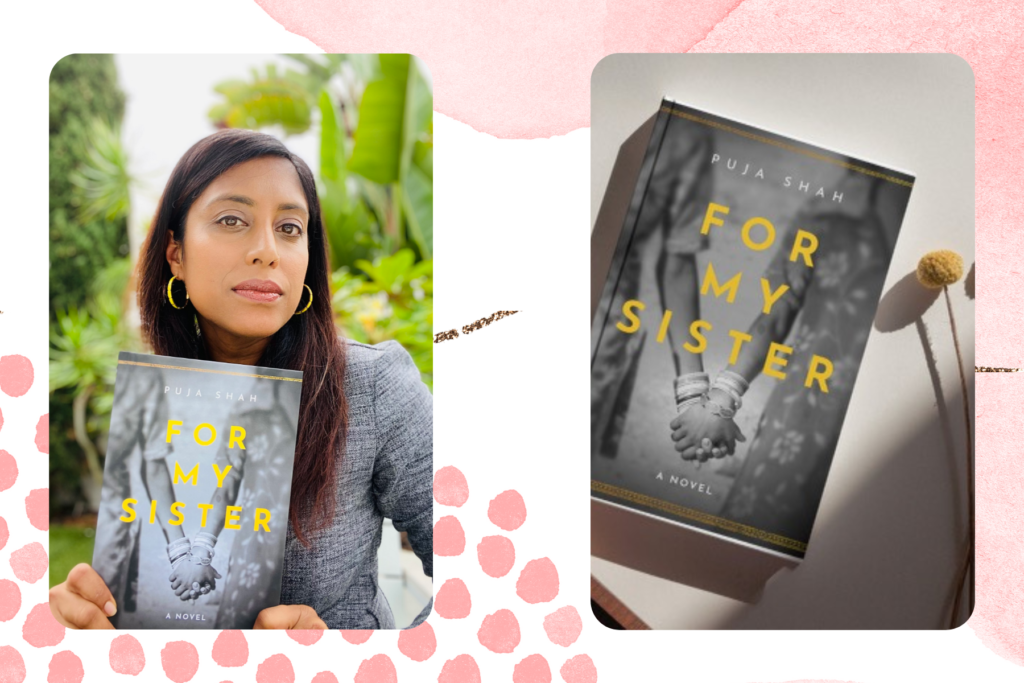

During the research of my upcoming debut novel, For My Sister, I interviewed a number of nonprofits such as Oasis India, O.U.R. Rescue and Child Rights and You that inspired me. I saw their driving efforts to meet the needs of fulfilling girls rights in India and at a global level.

For My Sister is a novel that follows the journey of light and darkness with Amla and Asya: twin sisters trafficked into India’s notorious Sonagachi district. Can the power of poetry, mindfulness, and sisterly love bring them back home and to each other?

What I learned is that while fiction, the story of Amla and Asya is all too real.

Sasha K. Taylor, child marriage survivor and advocate, says,

“Bravo! Puja Shah writes an emotional issues-focused fictional novel centered on the story of twin sisters Amla and Asya, whose attempt to escape a child marriage fails and they end up being trafficked anyway. The reader will find themselves vested in both sisters’ lives while gaining insights into the realities our fictional sisters endure — realities millions of real girls across the globe face every day. Puja Shah is precisely the fiction writer the literary world and global readers need to transcend to an empathetic place to finally begin understanding the plight of women and girls across the globe who are sexually exploited and abused, forced into unwanted marriages, and trafficked, by those they may trust the most… It is happening right now, as you finish reading this sentence.”

So often as artists, we express ourselves through the medium that we are called to. For me, this was writing. What started as a story, became a deeper calling for me. A cry for social change. A commitment to awareness.

So why write for social change?

1) There is a purpose behind your vision.

Writing for social change doesn’t mean you will change the world overnight, but it adds to the larger collective efforts toward social justice by helping those who have been second-class citizens of the world to feel validated and understood. Even if you are not an expert on the topic you feel called to share about, align with the causes that are doing the work on it. Like Gandhi believed, “In a gentle way, you can shake the world.”

2) Your self-expression contributes to meaningful conversation.

You’re generating thoughts for important discussion around social issues. As Roxanne Gay states in her course on social change, “when your work starts this conversation, you are setting the framework for productive cultural critique.” Discussions are where questions like the ones I had as a young girl can arise. There is a sense of inquisition when someone is confronted with something that does not feel right. What isn’t working? What isn’t fair? Who is being marginalized? What do we need to understand to elevate society as a whole?

3) You are giving voice to those who may not be able to express themselves.

This is the heart of why I wrote my novel. When you share a story of someone whose experience has not been heard, you are providing a place for others to understand this experience.

4) It comes down to compassion.

Your work is the vehicle of compassion that can bring forth awareness which can lead to change. As a yoga and meditation instructor, this inner place of compassion is one that reminds me we are not all that different. The girls across the world that I write about, could love the same music as my best friend, and have dreams like my sister. So share your work for them. It’s why I did…for my sister.

“For My Sister is a novel with a social conscience illuminating the epidemic of human trafficking. It will break your heart, open your soul, and ignite a fire within to become part of the solution. Share it far and wide with all of your sisters.” — Arielle Ford, International bestselling author of The Soulmate Secret

Want to be a bigger part of the conversation? Check out the causes Puja highlights as ways to help trafficked girls globally by visiting her mission page here.