Join me on this journey of re-constructing my Pakistani upbringing, where shame and guilt are used as gatekeepers to prevent family issues from seeping through the walls and into the public sphere and what it’s like to lose a parent to mental illness.

I am rebelling and I’m glad you’re here, rebelling with me.

Post-natal depression and psychosis were foreign terms in 1997, especially in Lahore, Pakistan. However, there is much conversation around the ‘baby blues’ in today’s world and is a fast-growing issue among South Asian Women compared to White British females due to relationship difficulties, financial difficulties, lack of social support and language barriers (Sihre HK, Gill P, Lindenmeyer A; et al, 2019).

Early Loss

I don’t remember much of my early years living in Pakistan. My brother and I were passed around from relative to relative after my mum could no longer look after us. During this time, my dad was working in England to make money to send back for our care. We soon joined him, when I was 6 after he remarried. I was always curious about my mum and what had happened to her. But it took me until I was 10 to be able to ask my dad, “why was mum unable to look after us?”

My mum was someone I spoke to on the phone once a year. Dad would buy a calling card to make international calls to Pakistan and we were told to speak to our mum. My brother distanced himself and avoided these calls. I followed in his footsteps, not because I didn’t want to speak to her, but because I felt guilty for wanting to know my birth mum when we now had a new (step) mum. The calls lasted five minutes asking how the other was, what was eaten in the day, and then complete silence until my dad took the phone realizing there was nothing else to say.

I was 11 when I found out that my mum had Postnatal Schizophrenia. I did what any other child would do. I dove into the internet. I read the words, ‘dangerous,’ ‘psychotic,’ and ‘violent.’ I was confused. I was frustrated because I couldn’t recall anything about her. But when you’re young, you also feel anything is possible. So I detached myself from those labels and refused to define my mum as any of those things. I would spend hours on the internet searching for treatments for her, aspiring to one day maybe treat her myself. Any ounce of hope that came my way, I took it. At the time, I never shared these thoughts with anyone. I cleared the browser history so my parents wouldn’t know. While my thoughts would fester from “will I be safe around my own mum?” to “what if one day I wake up and she is no longer in this world?” Despite being the quiet girl on the outside, my inner- world always felt so loud.

I look back and imagine how difficult it must have been for my dad, who is a quiet man too, to navigate how to talk about something like mental health with his children. Especially since issues like this are taboo and often ignored in the society in which he grew up. If I could go back, I would ask him more about the diagnosis. The only thing that stopped me was the discomfort of having him recall something he had never spoken about. I would shy away and rarely challenge these unspoken themes because it simply felt wrong. Nevertheless, finding out about my mum’s diagnosis at that moment secured my passion to help others with mental health difficulties.

[Read Related: Supporting the Mental Health of South Asian Aunties and Uncles]

Mother Wound

Before I knew it, I was already internalizing the emotions I felt towards my mum and the mother’s wound was exposed for everyone to see. Bowlby’s Attachment Theory states that children with inconsistent parenting are vulnerable to experiencing anxious attachments. This is when parents are inconsistent in meeting their child’s emotional and physical needs, and the child becomes more likely to be afraid of abandonment. I read this at the age of sixteen and it provided the most insight I’d ever had in my life towards an explanation of why I also felt that way. I learned from rumors and gossip that my mum was unable to look after me, didn’t attend to my basic needs, and at one point had felt afraid she would harm both me and my brother. Attachment styles also show up in adulthood. My past relationships would have me feeling like I was on an emotional rollercoaster, constantly worried about being abandoned and looking for that reassurance.

From the beginning, my dad and my mum (step-mum) would often look at me as if I were different like I was living in the shadow of my mum’s mental health. I spent hours isolated in my room and lost in my thoughts. From a young age, it had been implied that I would end up like my mum. Relatives would belittle me for staying within the four walls of my room and say, “your mother was also like this when she was becoming unwell. You don’t want to end up like her. We don’t want to see a repeat of what happened to your mother.” This allowed my unhealthy behaviors to manifest and start to define me.

When I was twelve I met my mum after 9 years. She lived with her older sister in Pakistan, who looked after her. Tears streamed down her face — I wondered whether a hug would be appropriate for my own mum, there was so much distance between us, even though she was right in front of me. During my time with her, I grew to learn about her silence, her depressed composure, and the hours she spent in bed becoming thin to the bone. I didn’t understand much of what was going on with her at that time and was experiencing mental health difficulties myself. I was told how she would support my auntie in looking after my younger cousins and I wondered “why not me, then?”

[Read Related: I Think you Should Start Therapy — Processing Trauma as a South Asian]

Coming of Age

I didn’t see her again until I was 18. As a young adult, my understanding of mental health developed more. This time, seeing her was different. I was proactive in my interaction with her and supported her in simple day-to-day things such as having a shower or eating. I remember spending two hours trying to get her out of bed to freshen up — slowly comprehending the role switch between us, she was now the infant and I the mother. At first, I felt empowered, but when the lights went out, I escaped to the rooftop, feeling more alone as I came to know who my mother was. I can sense the heaviness I felt in those moments as I recall this. Little to my awareness, my fight and flight mode was activated, and I was disconnected from myself and the world around me.

Now I’m 24 and we talk weekly. Our conversations last up to 20 minutes on days she is willing to speak. To this day, I sometimes feel haunted that I am unable to remember any memories of my mum from my early years.

I write this contemplating the expectation that I might need to take care of my mum one day. Some days, this can be a difficult thought, because I think of how little I know this person despite my many attempts. I’ve been told how my mum was lively, sporty, and wrote poetry like me. It has taken me time to accept that this person was someone before she became unwell. While I did not know her, I grieved at the idea of her. I wonder if this makes me a bad person. I went through emotions of denial when I tried to develop a relationship with my mum and became angry when she would not open up. I thought encouraging her to speak about her emotions would allow her to be seen and heard, but I was a stranger. How could she open up to me? Eventually, I buried my hopes of one day having that mother-daughter relationship I had always wished for

A part of me felt guilty but through therapy, I’ve been coming to peace with the idea. I received school counseling at school when I was 12 which I found helpful. Another secret I hid from my parents. Though in those sessions, I was selective about what I shared because being the only Brown girl in an all-White school – there were things they would never understand. Following those years, I was in and out of therapy, meeting the next therapist with open arms, but still finding myself holding back. Until I finished university and realised how much of my childhood trauma was leaking into my adult life. I knew I needed help. It just took making that one decision that felt right. This time I didn’t just find any therapist, I found a South Asian therapist. Someone who would understand intergenerational patterns and Pakistani family traditions.

[Read Related: How to Find Mental Health Balance as a South Asian Millennial]

https://browngirlmagazine.com/mental-health-balance-south-asian-millennial/Before this, I had become quite disconnected from my ethnic and cultural identity. But I was willing to accept this and make a change. I refused to allow my upbringing to be my only perception of mental health difficulties in a Pakistani household. Therapy has truly taught me a lot and continues to do so even now. I shared my entire story in my first session and over time we revisited each segment of it when I was ready and spoke about it. I knew about attachment difficulties as mentioned earlier, but I didn’t know the severity at which they manifested in my everyday life. I increased my awareness of my emotional responses and how to nurse my mother’s wound. Though the most important thing I learned was about how trauma lives in the body. All those early years I had forgotten with my mum and those feelings of unsafety were no longer memories, but bodily responses. My feelings of anxiety were just one part of the story. On finding this out, I began to allow myself to feel what I feel (including the discomfort I avoided), speak my truth and think what I want — in hopes that I will, one day, shorten the distance between us.

I have learned so many things through this journey, but most importantly, I’ve learned the value of having difficult conversations. In South Asian culture we are so used to keeping our feelings and thoughts quiet. But, talking can make all the difference. It was revolutionary when I began to ask my dad questions about my mum. He had experienced his own trauma being an immigrant to a new country, trying to create a home for his children whilst his wife was unwell. He had made his own sacrifices as he knew my mum could no longer look after us and left my brother and me in the care of his sister. Only to then work long hours in a new country alone so that he would have enough money to bring his children back home to him. It was revolutionary, because as introverted as he was, he began to articulate his feelings about these difficulties. It was revolutionary when I showed that I was not going to be defined by the anxiety I experienced, but instead, I would be defined by my resilience. Most importantly, it was revolutionary when my story became my strength and not a vulnerability. I hope that in sharing this very story, I have shone the light on others who are unable to find hope in their own journeys.

If you or somebody you know needs someone to talk to, below are some helplines to contact:

In the UK:

-

Samaritans: To speak to someone, call 116 123. This is open 24 hours a day, 365 days. You can also email jo@samaritans.org.

-

Shout: Text SHOUT to 85258 or YM if you are under 19.

-

Childline: If you are under 19, you can also call 0800 1111.

-

Papyrus: 0800 068 41 41 Monday to Friday 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. Weekends 2 p.m. to 10 p.m.. Bank Holidays 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. Text 07786209697. Email pat@papyrus-uk.org.

If you are unable to contact the helpline, contact your local GP for an urgent appointment or call 111.

If you or somebody you know is experiencing a mental health emergency, call 999.

In the US:

- National Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741

- Call the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

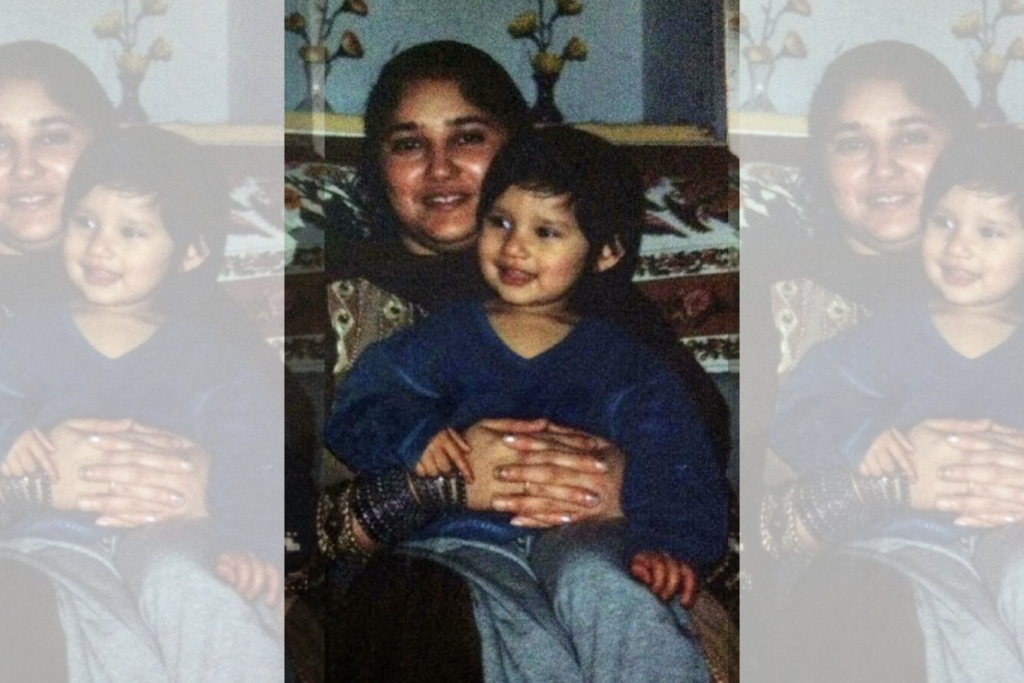

Picture Courtesy of Author